Part 2 Chapter 5:1 Everyday life in the village of Middleton - first days & a village crisis

From my book 'School Portrait' (McPhee Gribble/Penguin, 1987)

Middleton's First Days

When I arrived at school on Monday 30 April, the first of our twenty-nine village days, there were several kids waiting at the door of the classroom. Paul was one of them, his village costume in a white plastic carrier bag by his side.

'All ready?' I asked, remembering what had happened on Friday and wondering what sort of mood he was in this morning.

'I think so,' said Paul. He reached into the back pocket of his jeans and handed me a scrap of paper. ‘Here's the stuff you asked me to write.'

He disappeared into the darkness of the gypsy cottage, while I read his note which said:

Make a war, maybe.

Make the town go on for longer:

Invite another class to join in.

Paul had always been someone whose imagination was stirred by the grandiose, and I wondered, as I looked at his suggestions, whether our village would be big and exciting enough for him.

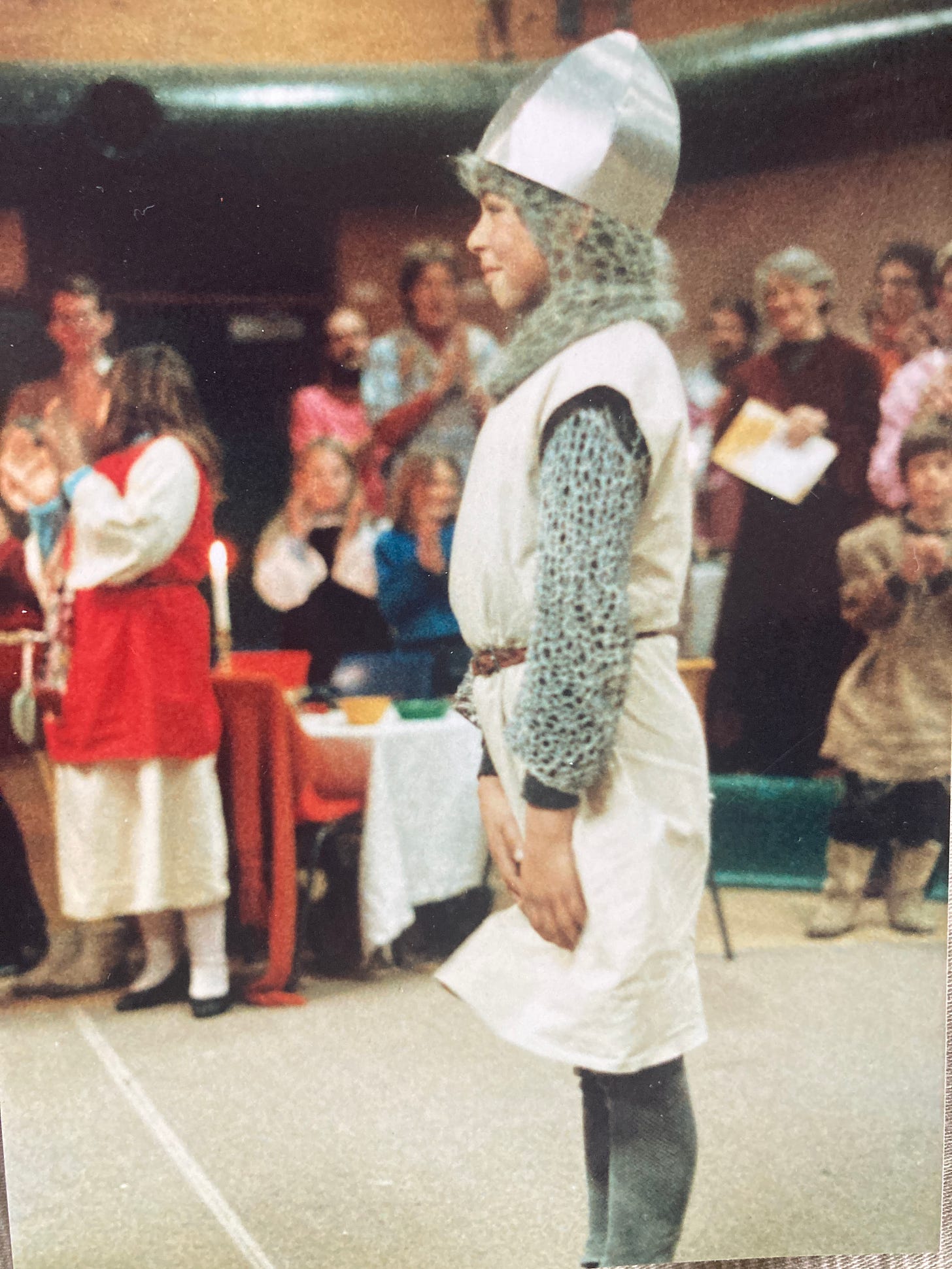

Mark and Eli walked past me, heading for the forge out the back, and looking for all the world like a couple of medieval craftsmen on their way to work. Eli had a hessian cloak and pointed hood, and was slightly stooped (being much taller than his friend Mark). Mark was wearing an imitation leather apron, and had in his purposeful gait the air of the highly skilled and well-respected village blacksmith.

A couple of nobles swept in - Nina and Rachel, in long shining dresses and with their hair up, followed by Ra (as the steward's son, Sir Edward) with a brightly coloured top and hose. They disappeared under the balcony and through the arched door of the manor house.

I went over to the three steps leading down to the village square.

We'd done so much preparation for this moment, but still I felt on edge, as if there were something I should be doing. I was excited, certainly, and my sense of anticipation heightened as kids arrived in their twos and threes, wearing their new medieval costumes and giving life and colour to our collection of buildings.

But I was nervous, too, because I knew (from one of our previous villages) that it didn't matter how much work had gone into the preparations, there was always the possibility that, in the end, it just wouldn't work. And this one was more ambitious and riskier than any we'd done before.

By about 9.20 a.m. most of the kids had arrived. Some were in the toilets getting changed, others were in the village square admiring each other's new look. Kids bustled in and out of their cottages, and those who were waiting for Effie (the travelling saleswoman) to arrive with their orders were getting impatient.

Anna emerged from her room in the monastery, carrying the cooking equipment and ingredients for the monks' first meal, and wearing a beautiful jet-black monk's habit, which her mother had made for her.

At 9.30, Allen and I called a meeting in the village square.

'Before we start the village this morning,' Allen asked our assembled group of forty-eight, 'are there any problems that need to be sorted out?'

‘Where's Effie? ... Can we start up the forge straight away? ... When can we start cooking? ... Can we nobles meet soon to make plans for our May Day celebrations?'

As Allen answered questions and helped calm the over-excited ones, I looked around at the group. Some kids, like Paul, seemed impatient to begin. He was sitting with the other gypsies, wearing a green, short-sleeved tunic with wide frilled collar. It was gathered around his waist with a thick rope belt, and he had a green felt hat on, the type worn by traditional Swiss farmers. Anna too looked excited. She was flushed and rather loud. Dan and Chris sat together, quiet and a little withdrawn. Dan loved to dress up, and he was perhaps both pleased and self-conscious about his monk's habit. Chris's distance, I guessed, had more to do with feeling out of the swim of things because of his recent absence. His costume was unfinished, and he wore jeans and a green jumper.

After the meeting, we all went to our cottages. I followed Anna and Dan into the monastery, and we lay down on the floor and pretended to be asleep, as we would do at the beginning of each of our village days. Then Allen blew on his bugle.

The village of Middleton was born.

'Come on you lazy loafing monks! Get into the Abbott's house for the meeting,' shouted Anna.

'Get stuffed Anna,' one of the monks close to me murmured under his breath.. The rest of us mumbled morning greetings to each other, commented on the weather, then shuffled down the narrow corridor to the Abbott's house. We crammed ourselves into the tiny room. 'OK, you monks,' said our Abbott. ‘What are you all doing this morning? I'm going to cook the meal.'

‘I'm going to mix herbs and look after the sick,' said Jessie, whose village name was Brother Albert.

‘I’ll help Brother Albert,’ said Jenna.

'Brother Henry [Dan] and me are going to do some illuminating,' said Kleete. 'Can we go now?'

'Just wait a minute,' I suggested, 'until we've got everything organized.' I felt it was important that no-one rushed thoughtlessly into the day, that we had time each morning to pause and discuss our intentions together.

‘You're not in charge here, Brother Robert,' Anna snapped in her haughtiest upper-crust voice. 'Yes, you two may go and start.' She was right, so I swallowed my protests.

Dan and Kleete left, and were soon followed by the other monks, Matthew to collect taxes from the villagers, Shaun and David to make a front door for the monastery, and Jessie and Jenna to prepare the infirmary for any sick or destitute villagers who might need help. Anna hurried off to the kitchen to get our lunch organized, while Mike and I sat together in the church to plan the village's first church service, set down for the following day.

During the previous week, Mike had made some small prayer books which included the Lord's Prayer, the Prayer of St Francis, and several other well-known ones, and we chose a couple for the service. We also borrowed a Bible from the school library, and found a short reading. I volunteered to preach the sermon, and he said he'd organize for a collection to be taken. I left him looking over the prayers.

I could hear various street cries coming from the village outside the monastery walls, amongst them the voices of gypsies offering to tell fortunes and bartenders selling drinks and biscuits in what sounded like a packed ale house. On my way out to get a taste of secular life, I met Paul and Chris at the monastery door.

‘Money for the poor, money for the poor,' Chris said, thrusting his hand out. 'We've come to the monastery because we're poor and we need some money.'

"You're poor already?' I exclaimed. 'Oh well, come in, my children. Come and tell me your problems.'

They followed me back into the church, and we sat down.

'So you need some money?'

'Yes, lots of money,' said Chris, with a smile.

I looked over at Paul, who had said nothing. He was stooped, almost cringing, in the style of the hunchback of Notre Dame, his eyes pathetically avoiding my own. I was interested in how quickly he had lost himself in the role play. ‘I thought you were a fortune teller. Aren't you getting any money from that?'

‘No money... very poor,' he said with a thick accent. Paulo, his character, was from Spain. 'Need much money.’

'But I haven't seen you or any of your gypsy friends at any of our church services. Perhaps your poverty is a punishment from God for your ungodly ways. Had you thought about that?'

Paulo straightened himself up and looked me in the eye, sensing that some kind of criticism was being made, some kind of challenge was being thrown down. He responded in role.

‘I God. You give money,' he said.

‘No, you don't seem to understand, my child. God is in Heaven, and is looking down on all of us. If you don't do as God wants, then He will be angry and you will be punished. When you die you will go to Hell.'

‘I from Spain. God from Spain. I God,' he said grandly, expansively. 'You do what I say or I be very angry, and you be punished. Give us money!'

"You are saying very wicked things,' I replied, pretending to be shocked. Shaun and David, who were cutting out a cardboard door for the monastery in the dining room next door, watched the scene, both amused and slightly puzzled. 'And in God's house too! Get out, both of you, and mend your ways. God will forgive you your wickedness if you repent.'

Chris was smiling broadly, and I was struggling to keep a straight face. But Paul was completely in character, and he walked out of the monastery behind me, mumbling curses.

I walked down to the village square, and was suddenly aware that the village was oddly quiet. I could hear voices from inside the manor house, where plans were being made by the nobles for the May Day celebrations at the end of the week, and Anna, the jeweller, was sitting in her cottage threading clay beads onto thin wire. But most of the other cottages were empty, and the ale house was deserted.

Perhaps everyone was packed into the kitchen, preparing food? Before I could investigate, Ra and David came running in from outside, laughing about some shared joke. Ra went into the manor house to join the meeting, and David brushed past me to get to the gypsy cottage. They were followed by half the village, most of whom went straight to the ale house, where Peter, the owner, immediately began to take orders for food and drinks amidst something of a party atmosphere. What was it all about?

When the rush had died down a bit, I asked Peter what had happened. His eyes danced as he told me how he had organized a wrestling match between Ra, one of the strongest in the class, and David, and how he had won a small fortune in bets because David had won. They had rigged the fight, and both David and Ra had received pay-offs.

While I was wondering about the morality of all this (in my role as teacher rather than monk), Jessie came to see me. She had volunteered to read from the Bible during our monks' meal, which was otherwise to be eaten in silence, and she wanted help in finding something suitable. We settled on a section from Genesis. The story of the Creation seemed appropriate for the first day of our village.

There were times, during that first morning, when I felt rather superfluous. I could see the stained-glass window people working purposefully with Bernie (who had come in for an hour or so), Anna S. was making her jewellery, the blacksmiths had the forge going and were bending metal, and the ale house people were being run off their feet serving apple juice and cooking rather messy looking pikelets for up to twenty customers at a time. In the kitchen, the bakers were making biscuits, and some of the village wives were chopping vegetables for a salad or heating up a rice dish brought from home. Nobles strolled from cottage to cottage, picking up simple wire bracelets from the jeweller, tasting a baker's biscuit or one of the pancakes that Martha, the shepherd's wife, had made. It seemed that everyone was busy except for me.

But at other times, I seemed to be trying to do five things all at once. Anna the jeweller wanted more wire, Shaun needed help with the monastery door, Jenna was bored in the infirmary because no-one was sick, the beggars were asking for more money, kids wanted tables for their cottages, Mike didn't fully understand one of the prayers he had chosen, and Effie wanted to talk about where the real money was coming from for all the supplies the kids were asking her to buy. It was something of a relief when Anna announced that our meal was ready.

The monks' meal was my favourite part of the day. We assembled in the Abbott's room, and then, with heads bowed and hands clasped in front, we filed through to the dining room, accompanied by a recording of a Gregorian chant I'd found the night before. We took our appointed places at the table, and ate in silence as Anna served us with fresh bread, fried mince with onion and tomato, apple cakes made by the village baker, and apple cider from the ale house. We could hear the blacksmiths' voices and the metallic ring of their hammering outside the window, but inside the only sounds were the occasional clink of cutlery and Jessie's steady voice as she read:

In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. And God said, Let there be light: and there was light. And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness. And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night. And the evening and the morning were the first day.

As I sat there in silence, I allowed myself to believe that I really was sitting in a medieval monastery, trying to put the cares of the world out of my mind as I contemplated the goodness of God.

After the meal and the clearing up, we assembled the villagers in the square, where Abbott Gilbert announced that a school for village children would start tomorrow. Then we changed back into our ordinary clothes, had a break when Allen and I encouraged everyone to play outside in the fresh air, and then spent the rest of the afternoon chatting and writing about the morning.

As the kids went home that afternoon, I felt as though an enormous ship had been laboriously launched. It looked as though she would float.

Anna was at her most efficient as she gave out the monks' jobs the next morning. She stood speaking to us from her desk in the cramped Abbott's room, occasionally referring to a meticulously ruled-up book entitled 'Book of Akownts and Jobs' which she'd drawn up at home the night before.

‘We will all be at the church service, of course. After this meeting, I want some of you to help me set up the village square, because we don't have enough room in the church for the whole village. Then, after that, Brother John, you make a doorbell for the monastery, Brother David and Brother Harry can continue with the front door, Brother Frank and Brother Henry can keep going with the illuminations, Brother Andrew finish collecting taxes, Brother Charles paint a sign for the monastery, and Brother Albert look after any visitors that come to the village. ‘Brother Robert,’ she said, looking at me, 'what are you going to do?’

‘Well, Father Abbott, l'd like to organize a small play for our May Day celebrations, a play about rich people and how Jesus said that it was harder for a rich man to enter the Kingdom of Heaven than it was for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle. Maybe we could make Lord Edmund give more generously to church funds.'

"Very good. You may do that.'

The church service itself was fun. Mike read his prayers and the lesson to a hushed congregation, and I preached a sermon in which I tried to illustrate, through a couple of simple stories, the importance of religion and the Church in the daily lives of ordinary people.

After the service, I met with the ten or so villagers who wanted to be involved in the play. It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God. What did this mean, I asked the kids. Did they think it was true? We discussed these questions for a while, and ideas began to emerge on how to dramatise the text. 'Let's have a scene where a rich and greedy lord, one with a sandy beard, crimson robe, and a name like Lord Edmund, refuses to help a starving villager... We could finish with a scene in Hell, like in that picture we saw a few weeks ago, with the lord being tortured over a furnace ... And we could have the starving villager end up in Heaven, being waited upon, fanned, and generally spoiled by angels, archangels and all that lot.' The villagers were lively and involved, and threw themselves into the rehearsal.

We rehearsed for most of the morning, and I caught only fleeting glimpses of what was happening elsewhere in the village. The kitchen and ale house were busy again, and the forge had a steady stream of onlookers, both from the village and from other classes in the school. I noticed, too, that Chris had found a niche for himself. The steward had given him a number of jobs for the manor house, and, when I saw him, he was measuring and cutting out a cardboard door.

But, that afternoon, as the kids talked about what they had done that day in the village, I felt a little uneasy. Many of them seemed to be living from day to day, with no real plan of action, no sense of what they were going to do with their village lives. There were exceptions, of course - the blacksmiths, Anna the jeweller, and a couple of the nobles. But many seemed to be still at the stage of seeing the village as an experience that happened to them, or that they shaped through their imaginations rather than through their planning and day-to-day actions. Paul, after dabbling with fortune telling, now wanted to join the monastery, because, he told me, ‘there isn't much else to do, and my mate Matthew needs a bit of company’. David had tinkered with some wood carving. Mike asked me to look after the next day's church service, and during the morning had been more interested in getting drunk with Paul at the ale house. Tegan cooked rather half-heartedly, and had that keep-away-from-me look about her that she adopted when she wasn't feeling inwardly pleased. Shelley was brittle and sensitive about the kids in her house and the ‘boring' role of reeve. Matt was waiting to see what each day brought, and resisted my suggestions that he go to the library to find out what a cellarer in a monastery actually did. Kate, Siobhan and Gail were making some delicious bread and biscuits, but didn't seem to be making plans or building up any momentum. Peter was making a fortune at the ale house, but I was concerned that he was somehow not a part of the community that we were trying to estabish, that he was more into schemes for diddling others out of their money, as he had done with the wrestling contest on the first morning.

That night at home, I wondered whether these kids were just too young for the sophisticated demands of an experience like this one. I'd seen, in my years as a secondary teacher at other schools, many seventeen-year-olds who had been unable to plan their time, who'd struggled with the possibilities and constraints of communal living, and who seemed content to accept whatever each day brought.

But, having articulated the concern to myself, I realized that it was precisely because these children needed help in developing plans and strategies that the village was potentially beneficial. It gave them time to work on these problems, in an environment about which they cared deeply. It provided them with an incentive to be more active, to tackle difficulties, to try alternatives, and to meet challenges. Over the coming weeks, I was to see many examples of this. It was no co-incidence, I felt sure, that kids from our school did well in Canberra's secondary colleges, where self-discipline and self-motivation were important.

Anna's Hassles

Anna had a rough time at the monks' meeting the following morning. She was all fired up about an incident from the day before, when one of the monks (Mike) and Paul had gone to the ale house and had pretended to get drunk. Mike had been giving her a hard time during the week, refusing to obey her orders and complaining loudly to the other monks about Anna's bossiness. Anna now saw her chance to get even.

‘The first thing for this morning,' she began, again in her haughtiest tones, very much in role, ‘is to deal with the matter of the drunkenness that happened yesterday. It was disgusting. It was an outrage.' She turned to Mike. 'Don't you realize, Brother, that you're a God person now. I'm fining you one shilling.’

Mike looked genuinely confused. Unlike Anna, he was new to the school and wasn't used to this kind of imaginative play. But he had worked hard during the lead-up to the village, and he was struggling against his instinct which, I felt sure, was to tell Anna exactly what she could do with her fine. He looked at the ground, and didn't say anything. But, when he became aware that the eyes of some of his mates were on him, he said defiantly, 'Well, I'm not going to pay. You can't make me.'

‘You'll pay, Brother, or you'll be sorry. I'll report you to the Pope, and you'll be in trouble with God.’

Mike didn't reply, and instead looked derisively at Anna, as if she were making a fool of herself. Anna was clearly upset by his reaction, and the rest of the meeting was rather disorganized. There was an undercurrent of rebellion in the ranks, and Anna found it hard getting any co-operation when she was trying to organize the jobs. I stepped in and backed Anna up, and the monks finally went off to their work.

'Are you OK, Anna?' I asked, deliberately using her real name.

'I don't like it how some monks don't obey me as Abbott,' she said. 'It really irritates me when a few of them laugh or tell me to get lost when I give them an order. So much work has been put into this village, and, I mean, they could wait till the village is over, I reckon.'

Damien the carpenter knocked at the door. He had been asked by Anna earlier in the week to make a lockable money-box for the monastery, for which Anna would keep the keys, and he was now waiting with the finished box. Anna told him to come in.

I asked if I could stay, and Anna, now back in role, motioned me to sit down.

The box was fitted together very nicely, with a hinged lid and padlock attached.

"Hey, that's really great,' said Anna. 'How much?'

'Ten shillings.'

'Ten shillings!' Anna shouted. ‘You've got to be joking. I'm not paying ten shillings for it?

Damien looked disappointed, He’d made a classy box, and he was expecting a high price.

‘Well, how much will you give me for it then?'

‘I reckon about two shillings,’ she said nervously, perhaps remembering the criticism she’d copped in the earlier drama session for being too free with monastery money.

‘Two shillings! Get stuffed! I've done all that work, and it's been a big waste of time! I had to pay money to Effie for the wood and screws and the lock, and I've had to go to the shops, and I've made it really good! Bloody hell, Anna, two shillings!'

They haggled for a while, but couldn't agree. Anna, who wanted the box very much, finally settled on four shillings. She stood for a moment in the middle of the room, staring at the box that was now hers, but clearly disgruntled with how the morning had begun.

As soon as Damien left, one of the blacksmiths knocked on the door. He brought a metal door handle (a short iron bar bent into a circle) that he had made, and which he told Anna had been ordered by the monastery earlier in the week.

‘I didn't order it,' she said rudely. She was in no mood for coping with the unexpected. 'I don't want it. Take it away.'

'Are you sure,' I said. 'It looks really good to me.'

'We can't afford it. Take it away.' And she brushed past him and disappeared into the village. Her mood had taken her beyond any quiet discussion with me about her difficulties, so I made a mental note to spend time with her later.

I followed the blacksmith out to the forge. He wasn't too upset, he told me. He was sure that they'd sell the door handle to someone else, and anyway, it had been fun to make.

The blacksmith's workshop had been built just outside one of the back doors, in a disused garden bed. There was an anvil on which they beat and shaped the white hot metal, and some tools and accessories - tongs, heavy hammers, a poker for the fire, a couple of pairs of thick leather gloves, and a bag of coal - lay around their workshop.

The forge was a focal point for visitors. Both the blacksmiths and Allen had been concerned about the safety of the people milling around, so they'd rigged up a rough timber barrier, or viewing platform, and that's where I now stood.

The fire was going, and Mark, Jamie and Ell were taking it in turns to crank the handle. The faster they went, the louder the roar of the flames from inside the forge. Mark had the gloves on, and it was he who was in charge.

'OK, that'll do. She's hot enough now.'

He picked up a thin metal bar about fifty centimetres long, placed it in the tongs, and then put it in the fire in such a way that the greatest heat was at the mid-point of its length. Then, every couple of minutes, he would take it out of the fire, put it on the anvil, and bang away at the weak point to cut it in two.

‘What are you making?' I called down.

Jamie came and stood next to me. 'It's going to be a knife; he said, 'for Lord Edmund.'

Eli had now taken over, and had managed to dissect the bar. He put one half in a bucket of water, and there was a whoosh of steam and an audible gasp from some young kids from another class who were watching with me from the barrier. Then he held the second half with the tongs, and put it back in the fire, this time heating one end of it. Every couple of minutes he would take it out, put it on the anvil, and beat the heated end to make the flattened blade of the knife.

Jamie went down to help with the hammering.

"Ready,' said Mark, and both Jamie and Eli raised small sledge hammers above their heads. Now... Eli... Jamie... Eli … Jamie… Eli.’ He kept the call going until the two had struck up a steady rhythm, and then left them to it while he cranked the bellows handle for a while.

I watched for about fifteen minutes, deeply impressed by their confidence and skill. Two of the three boys working in front of me had come to the school in the past year or so with very unhappy school experiences, considerable reading problems, and their self-images very shaky. As they beat the metal and stoked the fire, and as they answered the questions of an admiring audience, they looked like different people - taller somehow, self-possessed, and absorbed.

‘Steve... I mean Brother Robert. Could we talk to you please?'

It was Paul. David, his village son, was standing next to him, looking restless, not really wanting to be there.

'Sure. What's the problem?'

‘No, can we talk to you privately?'

Anna was close by, obviously engrossed by the activity at the forge, and I asked her if I could use her room for a while. She nodded distractedly, so we filed through the monastery and into the Abbott's house.

'Ageth here wants to get married,' said Paul. David squirmed and smiled uneasily.

‘Who to?'

'Alice, the shepherd's daughter.'

Anna R., whose village name was Alice, had arrived at the school the year before, and was considerably younger than both Paul and David. Up until the village project, she'd had nothing to do with these two.

'What does Alice say? And her parents?'

‘We've talked to them, and she wants to marry and her parents say that's OK. They're really keen, actually,' said Paul. David still hadn't said anything.

‘Well, you'd better get Alice, so we can make some arrangements.'

Paul and David disappeared, and I went to the monastery entrance to wait for them. There was a huddle of villagers standing there.

'Is Ageth going to marry Alice?' asked one. The village gossips were obviously already at work.

David and Paul returned with Anna, and we went back into the Abbott's house.

"So you want to get married,' I said. ‘Have you thought seriously about the consequences of this? There's no going back once the step has been taken. It's a marriage that will be blessed by God, and there's no possibility of divorce in our village.'

'Yes, I'm sure,' said Anna.

‘I'm not one hundred percent sure,' said David.

'Oh come on, you said you would,' said Paul vehemently. ‘We've made all the arrangements. It would be great fun to have a wedding in the village.'

"Yeah, I know, but I'm just not sure, that's all.'

‘Well,' I said, 'it seems to me that, Ageth, you have to do some more thinking. If you're sure, then we'll talk again and make definite arrangements.’

Paul looked disappointed, Anna anxious. Both clearly wanted the marriage. Anna went back to her cottage, and the two boys (I found out later) went off to the boys’ toilets. The conversation went something like this.

‘You've got to marry her. I've already made all the arrangements.'

'Like what?'

‘Well, I've bought the rings, and I've got presents for you both, and I'm just about broke!'

'But I don't really want to ...’

'Dave, you have to marry her!'

Well, I don't want to, but you're my father, so I guess I have to.'

There was a longish pause, with David looking unhappily at the ground.

'Oh, make up your own mind,' said Paul.

'I won't marry her,' said David quickly, before Paul changed his mind. ‘I really don't want to, Paul.'

'Well, I'm not telling Anna. You've got to tell Anna.'

They came to see me soon afterwards to tell me the marriage was off. The village was disappointed when the public announcement was made - apparently just about everyone had heard the rumours, and was looking forward to the wedding.

But the first seeds had been sown, seeds that would bear fruit later on in the village's life.

Towards the end of the morning, Jessie and Anna came to see me. They both wanted to leave the monastery, they said, to become ordinary villagers. For Jessie, it was fairly clear-cut. She wanted to be more active in the village, and to be a member of a family. She was finding her job in the monastery's almery and hospital boring, because 'no-one ever gets sick.' But Anna was more torn. It was the end of a busy and hassled day for her, and she was feeling that being Abbott was too hard. On the other hand, she liked her room and the importance of her job, and she knew that she wouldn't be able to step back into the role of Abbott if her life as a villager didn't work out. So she was risking much more than Jessie, and, though she hankered for the outside life, she wasn't absolutely sure yet that she was ready to make a final decision.

I tried to convince both of them that we could work together to make the monastery into a more exciting, dynamic and varied community. I could see it, I told them, becoming a more open place, with married people (perhaps like Jessie) living somehow within it. Perhaps it could try to build up its wealth by going commercial - making and selling goods and pardons, buying up houses from the Lord, and becoming a feudal power itself. Some prudent marriages could be arranged, I said as I got carried along by my vision, to increase the power and wealth of the monastery. I could see a time when the monastery would begin to rival the manor house, and that there could be two sub-communities, Middleton East and Middleton West, which competed, traded, had disputes. We might end up with an overlord to create harmony, or there might be some kind of simulated war if things got bad. The manor house crowd might break away from the established religion, we could have our own Reformation! We might . .

'Steve,' said Jessie with an indulgent sigh. ‘I just want to have a bit of fun as an ordinary villager.'

The next day was the last day of term for the school, and the day of our May Day celebrations. Peter of Curtainia (Peter, the secondary Drama teacher) was with us for the day. He told the kids at our morning village meeting how he had been travelling in the Holy Lands and that he had some stories of the Crusades which he would tell us later that day. Then we broke into groups to make last minute preparations: the making of spinach pie, punch and biscuits; learning from Peter how to dance around the May Pole; and collecting equipment for the May Day games.

Then the celebrations began. The Lord crowned Nina Queen of the May (voted by the group as the 'spunkiest), and she made a little speech thanking the Lord and officially beginning the fun. Peter told his gory crusade stories, and we watched and sang while the dancers danced around a May Pole which some of the villagers had erected and decorated with coloured ribbons earlier. The villagers made up an extra verse, ‘Here we go singing the Lord is a fink', which was sung with great gusto, and much to Allen's feigned dismay. The Lord's wrath was turned when Peter explained that the word 'fink' was Middle English for 'fine king'.

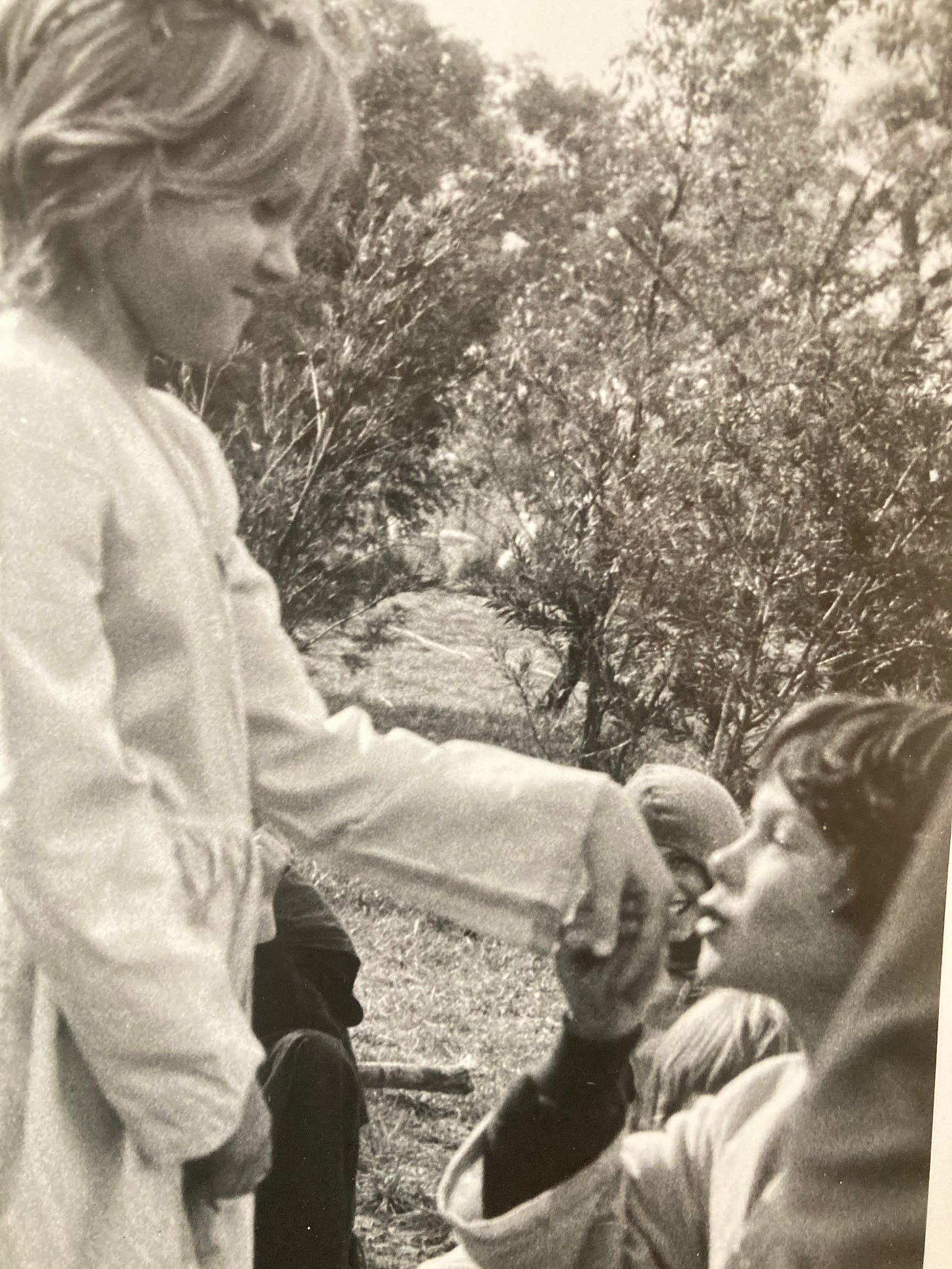

Then we went to the oval for games. We had arm wrestles and races, then back to the village green for the food. As we ate, Ra announced a competition for the bravest - boys had to line up to kiss Nina, and girls had to kiss him. Contestants lined up, and, to the shouts and cheers of onlookers, took their turn, some gallantly kissing a hand while kneeling, others giving a hasty and embarrassed peck on the cheek. The Lord awarded the prize to Nina and Ra.

After the food, we had a competition for the most handsome man and most beautiful woman (all these games and competitions were based on real medieval May Day customs), and then our small group performed the play about the greedy lord's fate in Hell. Again Allen was suitably offended and angry, much to the kids’ delight. We tidied up after the play, had a biscuit each from the pile that had been baked that morning, and the kids went home for their two week holiday.

It had been a day full of laughter and fun.

But Anna had been very down in the dumps, and on the edges of it all. She told both Allen and me separately, once in tears, that the Abbott's role was too much for her, that it was not turning out like she thought it would, that she'd like to be a blacksmith and be actually producing something. Earlier in the day Jessie had written to the Pope (Vaughan, another teacher in the school), and, after a superb audience with him to which I was invited, received permission to leave the monastery. But there was still something that held Anna back from taking this step. When she told me how she felt she wasn't coping, I suggested that I become the Abbott and she be my off-sider. She was emphatically against this. ‘If I'm a monk, then I want to be the Abbott!'

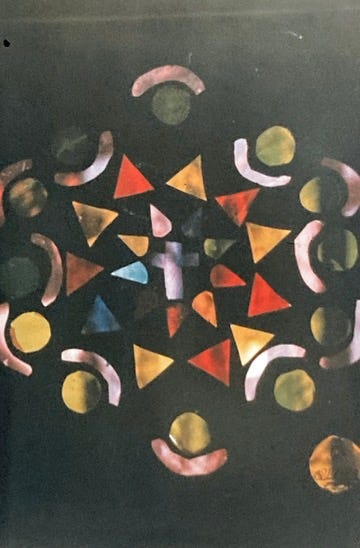

At one stage during the morning, while the villagers were spread throughout the village eating the spinach pies and drinking the punch, Anna had wandered into the church, where a couple of the stained-glass window makers were proudly showing me their superb work. 'It looks quite disgusting to me,' Anna had said in her Abbott's voice, and had then turned around and left. The two craftsmen were startled and a little upset, and I went out and told Anna how rude and insensitive I thought she'd been. She denied it, but was clearly unsettled.

I thought about her behaviour again after the kids had left. Anna saw herself legitimately playing the part of the powerful and cruel despot, and so, from her perspective, it was Abbott Gilbert and not Anna who was being rude.

But it bothered her that the monks didn't obey her every command, that Damien hadn't respected her special position, that others didn't live in this imaginary world as intensely and completely as she did. And so, at a more personal level, she wasn't simply acting a part when she called the stained-glass windows ‘disgusting'. She was also unloading some of her confusion and discontent.

I thought about the village life she'd been leading over the past four days: the school where she'd taught some village children the ABC; the insights she was getting into life in a monastery and other small communities; the lessons she was learning in leadership; the opportunities she was having in her fantasy to act out some aggressive feelings; the weighing up of options for her as she balanced the attractiveness of being a blacksmith and leading an ordinary village life against the power, prestige and privileges of being an Abbott; and the maths she was using to pay people and to keep records. Was the potential learning implicit in these experiences now being threatened by her growing sense that she couldn't cope? Or, when the village was over, would she look back on these difficulties as part of an exciting period of growth?

A Village Crisis

Two days after we came back from our holidays, the village of Middleton was embroiled in a major crisis. There had been difficulties betore, but they had been individual and minor. This one involved us all.

In fact, the new term began very happily. We spent an hour of the first morning role-playing, occasionally stopping to talk about the characters we were portraying, and distinguishing village roles from our everyday selves. Allen and I were surprised by the ease with which everybody got back into it; the kids seemed refreshed by the break and eager to begin village life in earnest. Anna, for example, who had spent the last days of the previous term rather weighed down, came back keen to continue as Abbott. She'd spent hours with her older sister during the holidays making signs for the Abbott's house, including one which read:

ABBOTT'S HOUSE

KEEP OUT

OR GOD WILL GET YOU.

We still didn't have any animals - the goats, sheep and chickens arrived a week later - but that didn't deter our shepherds, Yvette and Amy S. As soon as Allen had blown the bugle on that first day, they had a chat together in the village square about the weather and their daily chores, and then wandered around the hill at the back of the school, lifting imaginary sheep out of bogs, teding lambs by hand, sowing seed, herding cows in to be milked, and so on, quite lost in their own world. Allen called me to the window several times to watch them.

But on the second day back, a noble reported that some money had been stolen from her private area in the manor house. As soon as we reminded the group about the consequences - that we'd stop the village until we could sort out the problem - the money turned up. But, on the following day, more money went missing. When we were sure that it wasn't a false alarm and that it wasn't going to be returned, Allen and I announced that, on Friday, the village would stop, and that we would meet instead as a class to discuss the problem.

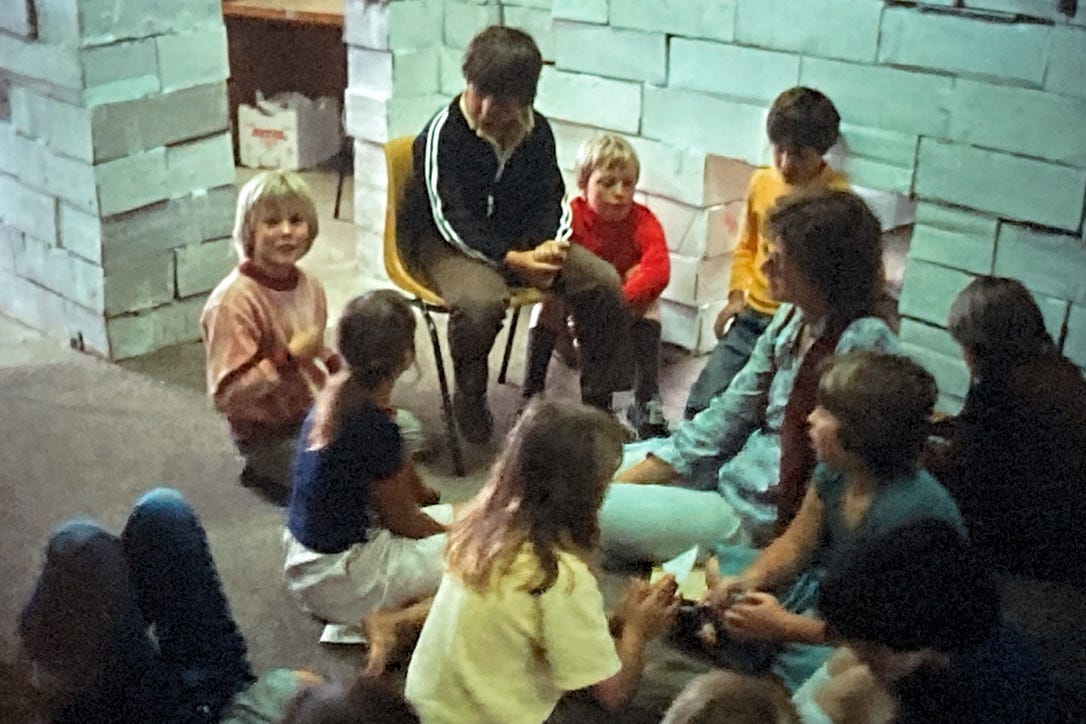

We sat in the village square on Friday morning, in our everyday clothes. Allen opened the meeting. 'The problem that we have to work on is this: we decided to make a rule that there would be no stealing, and some village money has been taken. What are we going to do?'

'I don't think it's fair that we stop the village,' said Ra from the balcony of the manor house. 'We don't know that it was someone from this class. Maybe it happened after school one day, when the classroom was unlocked.'

‘I think we should set a trap,' said one of the younger kids. ‘You can get this powder that you dust onto the money, then you leave it lying around. If someone takes it, the powder sticks to the thief.'

'I reckon it was someone from this group,' said Mark. ‘The money went missing during a time when we were all in the room …’

‘No it didn't!'

‘Well, I think it did,' said the kid whose money had gone. 'It was there when we started the village in the morning, but not there about half an hour later.'

"So I think,’ Mark continued, ‘that the person who took it should just put it back. We've worked really hard for this village?

‘But we said that yesterday, and it still hasn't turned up,’ said Rachel. 'I think it's partly the fault of the kids who leave their money around unguarded. It's like a temptation.'

‘Well’, said Ra, ‘I still don't think it's right that we suffer when it could easily have been someone from another class. There were kids from secondary in the village that day, and kids from other primary classes. How do we know that it wasn't one of them?’

‘I reckon our original rule against stealing was dumb, said Chris. ‘It's just not realistic. There was stealing in medieval days.’

‘But we made that decision, whether it was wise or not,’ said Allen, 'and we've got to face the consequences. Perhaps, though, this group will decide to change the rule?’

‘No, we went through all that before,’ said Nina. 'Allowing stealing would wreck the village.'

‘Well it's not looking too healthy just at the moment,' said Chris. ‘I reckon we should change it.'

Paul was sitting somewhere near the middle of the group, and his hand had been up for a while.

‘I think that the person who took the money couldn't be liking this village all that much. I mean, the person would know that taking the money would mean that we'd stop. Maybe that's why he …'

'Or she!' said Damien.

"Yeah, or she then - maybe that's why he or she did it, to stop the village.'

'Are you saying, Paul, that maybe we ought to be thinking of ways to help kids who aren't enjoying the village?' I asked. I was impressed with his lateral thinking.

"Yes, maybe that would mean there wouldn't be any more stealing.'

'Have you got any ideas about how we might do that?' asked Allen.

Paul thought for a second, then shrugged his shoulders. Not at the moment,' he said. 'Maybe something will come up.'

There was a silence for a while, and then we started going over old ground. Were other classes involved? How do we get the culprit? Why might someone steal? Could it be linked with some kind of loneliness or dissatisfaction with the village? Should we change the rule? Should we stop the village completely? The discussion dragged on for the best part of an hour.

‘I think it's time we had a break, said Allen at last. 'Could everyone quickly write down on a piece of paper what they think ought to be done. Then we'll knock off, and meet back here after you've played outside for twenty minutes or so.' The kids wrote quickly for about five to ten minutes, then went outside. Many were looking pretty glum.

Allen and I went up to the staffroom, together with Effie, Beth and Valerie (an ex-AME pupil who was in for the day), to compare notes. I was feeling rather discouraged. There had been no clear direction, nothing that we could get hold of to help find a way out of the predicament.

It was Beth who pointed out that we were trying to deal with too many issues at once. ‘It might help to separate them, and then to deal with them one at a time,' she said. So I found a quiet corner in the staffroom and started to leaf through the kids writing.

The more I read, the more hopeful I began to feel. There was an abundance of ideas and suggestions, evidence that the kids really cared and only needed help from us to deal with the complexity of the issues. I wrote out their suggestions in some kind of order, duplicated them, and then hurried back to the classroom.

The proposals and results of the ensuing discussion were as follows:

A. The Past - What Do We Do About What Has Happened?

1. We stop the village until we find out who has taken the money. [Ideas for finding out are (a) get everyone to write down who they think it was (b) question everybody (c) we all talk to kids we suspect (d) we count everyone's money (e) we ask the person to own up.]

The group voted against this.2. We keep the village going, and ask the person or people who took it to either say so now at this meeting, or tell Allen or Steve, or to quietly put it back.

Passed3. We compensate those who have had money stolen.

Passed4. We start the money again, with everyone having what they had when the village started.

Defeated5. We go to other classes and tell them how we feel.

Passed6. We ask outsiders where they got their money from before we sell them anything.

Passed7. We try to help those who don't like our village to like it.

PassedB. The Future - How Do We Stop The Problems That Stealing Is Causing Us?

1. We change the rule about stealing so that stealing is allowed.

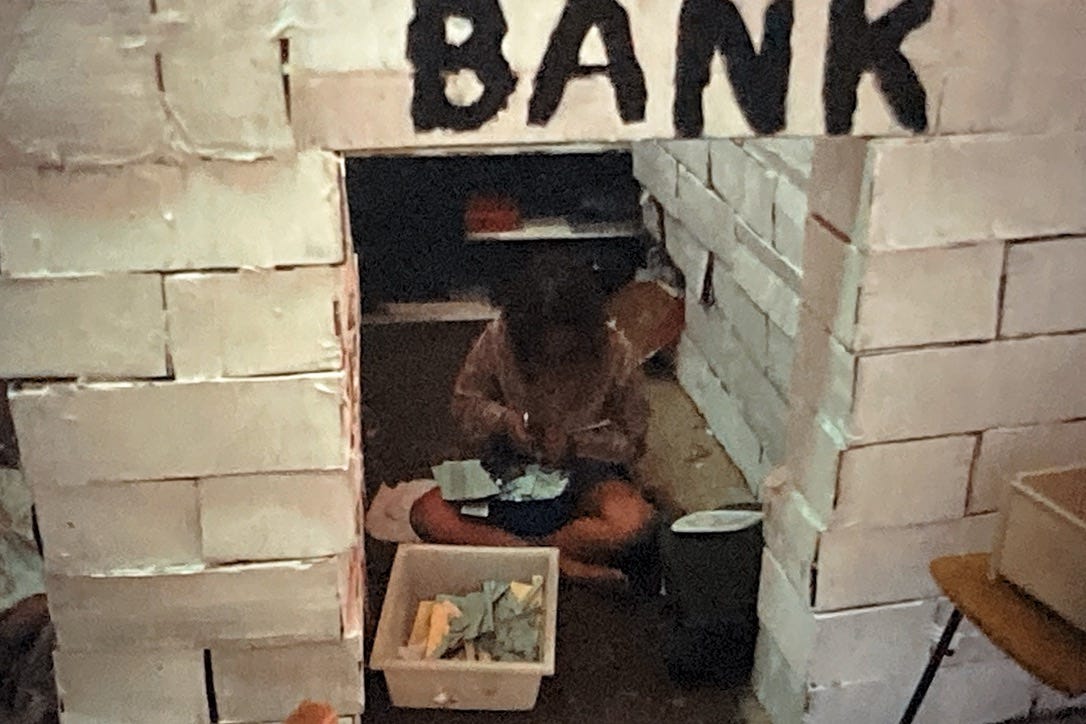

Defeated2. We have safe places to keep our money, like some kind of bank operated by kids, or a locked cupboard.

Idea of Bank passed3. We have pouch makers in the village, or kids make their own pouches, so that money can be carried around with you.

Passed4. We make outsiders pay with real money (which later gets exchanged for village money).

Passed5. We don't allow outsiders in the village.

DefeatedC. What Do We Do If There is More Stealing?

Allen and I left this one. We'd already spent hours on these proposals, and the kids were exhausted. We reminded them though that the issue would have to be dealt with if there was any more stealing.

As with the discussions about village rules, some of these suggestions were passed immediately, and others were debated at length. The kids talked about justice and rights, crime and effectiveness of various punishments, our feelings about the village, how society adapts as a result of difficulties (in this case through starting a bank and encouraging pouch makers), and the notion of compensation and its possible effects.

It was hard work, and tedious for some. But, as we approached the final proposal, the group sensed that we'd got over a hurdle, and the general mood lightened. At the end of the meeting, when it was decided that we continue the village the next day, Allen got out his trombone and we sang loudly in the village square. It was a celebration, though no-one said so, and deeply exhilarating.

After the project had ended, one of the parents wrote to me to tell me what this 'stealing incident' had meant to her family.

I'm not sure that I can put into words the feelings and emotions that the medieval village generated in our family. First, I'd just like to say thanks' for all your work, love and effort.

As a new boy this year, the village was particularly helpful for Cameron. Through role-playing and the undertaking of various jobs and responsibilities, the village gradually gave him a sense of belonging to the group and therefore the school. I feel that he integrated into the group more gently and effortlessly as a result of the project.

Cameron is quite difficult to inspire, as he has a rather cautious approach to life. The village helped, because the tasks were seen as unique and worthwhile, and for the first time ever, I saw him enthusing about something outside our home and farm. He was tickled pink that his garlic bread gained popular acceptance (and perhaps he felt that he did too); and was proud of the money he made.

For the first time he was inspired to look up information (on armour and weaponry, and later on medieval clothing). He still gets excited when he hears medieval names crop up in other contexts.

The major concept he took away from the village was the mechanics of group co-ordination and the necessity for trust. I discovered this through his reaction to the stealing episode. He was really discouraged by the loss of money from the ale house, and stopped wanting to wear his costume. He really had to grapple with this problem, and had a long talk to us one night about how he'd been spending money that wasn't his (from our change jar). The following night he told us he had stolen a packet of biscuits from the local shop and was devastated that he'd done it. Luckily the shopkeeper (a friend) had spotted him and made him return them to the shelf. We had a tearful family conference (Cameron's tears) where he told us how mad he was with the stealing in the ale house - and how rotten he felt that he'd tried that seemingly 'easy' way to increase your assets without effort. He sounded more grown up and articulate than I'd ever known him. He really understood the full extent of the concept.

We feel there would be no way that he could have learned to cope so well in the autocratic school he previously attended. We feel that there, he would have learned that it's OK to steal, providing you don't get caught and publicly shamed, whereas in the village, he learned that the thief's gain was actually somebody else's unfair and crushing loss.

I discovered, after the village had ended, that Anna had pilfered some money too. 'I took money from the monastery box,' she told me. ‘I shouldn't have spent it, but I did. I had the key of the box and whenever I ran out of money I just took more. I could have got chucked out as Abbott if anyone had found out, but no one noticed. I told everyone how much money there was, and I worked it out so that it would seem that there was none missing.'

After the discussions, Anna's embezzlements stopped.