Part 2 Chapter 5:2 Everyday life in the village of Middleton - death, marriage, fair, feast & finish

From my book 'School Portrait' (McPhee Gribble/Penguin, 1987)

The Death of Paulo

In the midst of these discussions about the stealing, and just as Allen and I were sitting down to lunch in the staffroom during one of the breaks, we heard some shouting from near our classroom.

'We protest! We protest! We protest!' came the chant.

'l’ll get the coffees,' said Allen quickly with a smile.

I went outside and found a group of kids marching with Paul at its head. They carried roughly made banners which read, ‘Don't wreck our village' and We Protest!'

‘What's all this?' I asked Paul.

‘We're protesting about kids from other classes pinching money and spoiling our village.’ He seemed more excited than indignant.

"Are you sure it's not going to backfire?' I said. 'Aren't you just going to stir up resentment against our class?'

‘We can protest if we want to,’ said Paul defiantly. ‘We don't want the village wrecked.'

"OK, I said. 'But I think it's a mistake.’

I returned to my lunch, but it wasn't long before I heard more shouting and scuffling, and it sounded more serious this time. Most of the kids involved had dispersed by the time I reached the scene, but I was told that some kids from another class had 'attacked' and had torn down the banners, claiming to be ‘riot police'.

I went looking for Paul. I found him, huddled alone in amongst the leaves and branches of an enormous gum that had toppled over a month or so before. He looked up at me, half-belligerently and half-shamefaced. I squatted down next to him.

‘How do you feel about what just happened?' I asked.

'Oh it was cool,' he said defensively. 'Bit of fun.'

I guessed that he'd got out of his depth this time, and that he realized it. ‘Well, come on Paul,' I said, feeling that any moralizing from me would only undermine any lesson that he may have learnt from the incident. ‘They'll be starting the discussions back in our room any minute.'

'I reckon the village is now wrecked,' said Paul as we walked back. ‘I’m sick of it, all this talking and never doing anything. I think we should end the village and do a play or something, something exciting.'

He brought his mood to the meeting about the stealing proposals, and sat on the floor picking at the carpet moodily. As each proposal was read out, he shook his head firmly, as if to say that nothing was going to salvage this disaster. Several times he told the group that he thought the village should end, but only one of Paul's friends voted with him when we decided by 41 votes to 5 to continue.

He arrived at school the next morning with his costume ready, and apparently in a much better frame of mind, influenced, possibly, by the group's new found optimism and enthusiasm. Soon after everyone had started their village work, I got a message from one of the villagers that Paulo the gypsy was very sick. He was lying in the monastery infirmary, attended by the doctor (Kate) and a couple of the monks (Matthew and Shaun). ‘What's the problem,’ I asked, and Paul groaned and held his stomach.

"He's having difficulty breathing, ' said Kate, trying to suppress a smirk. 'He's got the dreaded disease of choko-ilitis.'

I bent down over his prostrate body, and put my hand to his forehead. 'Yes, he appears to be very, very sick,' I said. ‘Will you leave us in peace for a while, while I administer the last rites'.

When the others had gone, Paul looked up at me, and with a broken and pained voice said, 'What ... are ... last rites?'

I explained that they were a kind of cleansing of the soul given to the dying, and that if he confessed his sins then he would surely go to Heaven.

‘Confess? What do you mean?'

‘Just tell me all the things you've done wrong,' I said. ‘Then God will pardon you. Otherwise you may be punished for any wrong you have done.'

‘Oh, said Paul. ‘There's nothing. There's nothing l've ever done wrong.’

‘Nothing? Absolutely nothing?’ This was disappointing. I’d hoped to get a few juicy confessions from him. He shook his head, then groaned, and I left him in peace. The others hurried in.

Some ten minutes later, Paul came up to me in the village square.

'Paulo, I said. 'You're looking much better!'

‘No, Steve,' said Paul. 'I want to talk to you for a minute, as Steve, not as Brother Robert. Do you think I could really die?' he asked.

We’d made a rule at the beginning of the village that no-one could change their character. Well,' I said, 'you'd have to ask the group - the kids, I mean, not the villagers. It was them who made the rule.'

The following morning Paul talked to the assembled kids. He explained that he wanted to die and then to resume village life as Don Carlos, with relatives in the manor house. There was a brief discussion and then a vote in favour.

Ten minutes later, as soon as the village started for the day, Paulo staggered out of his gypsy shack and died a melodramatic and noisy death in the village square. His body was taken into the gypsy house, and soon afterwards a stranger named Don Carlos was seen around the village.

Over the next couple of days, villagers were busy at various times, digging the grave, making the coffin, and carving a headstone. And in the scriptorium Dan and Kleete copied indulgences for sale to villagers who wanted to ease the passage of Paulo's soul to Heaven. I watched them over the scriptorium wall one morning, and for much of the time they worked in silence, occasionally showing each other their work and asking for a special pen or ink. Once Dan asked Kleete how to spell ‘soul’, and for couple of minutes they talked about the coming funeral.

‘They're digging a real grave, you know,’ said Dan. 'They're going to bury him.'

‘Just the coffin, they're not going to bury Paul. How would he get out?'

‘Oh, they're not going to really bury him,’ said Dan. ‘That'd be awful getting buried alive, don't you think?'

"Yeah. Yuk.'

‘I wouldn't mind dying in this village,' said Dan. ‘I reckon it’d be good to be someone else. It gets boring after a while just writing out stuff.'

Somehow I couldn't picture Dan trying to break out of what was perhaps becoming a rut. He was the sort of kid, I thought, who would resign himself to this drudgery. Much later, after the village had ended, I found out otherwise.

The following Friday 1 June was the day of the funeral. The grave had been dug and was over a metre deep, having cost the grave diggers many blisters. But neither the coffin nor the headstone were yet finished. That morning, the gypsies rushed to complete the work, and other villagers (including Don Carlos) chipped in with their help. At the last minute we were able to set up the coffin in the church.

Meanwhile, Paul had disappeared into the toilets, and had covered his face with large grisly blue spots over a white base of theatrical make-up. He got into the coffin, and we sent out word to the rest of the village that they could now come and pay their last respects.

Paul later told me (while I had a tape recorder):

I remember lying in the church with my face painted. You said to me before anyone came in, 'Now Paul, you can't laugh. If you laugh, then everyone will laugh.' Then the villagers came in and looked at me, and I had this big white face with spots all over it. I can remember Dave, my village son, he burst out laughing. He was supposed to be the last person to find it funny.

Then, as soon as they'd seen me dead, everyone left the church, and Tom ... Tom had to help me all the way with this, I couldn't have done it without Tom … Tom ran up to the bathroom and he got wet cloths and waited for me. I ran in with my monk costume and he quickly rubbed my face and got it all clean, and then I started getting dressed because I had to be at the funeral as Don Carlos. I was trying to put on my tights and it was murder. I ran through the church and someone saw me and said, 'Aren't you supposed to be in the coffin?' and I said No, I'm a different bloke!' I ran out and watched them carrying the coffin out ...

While Paul was getting changed, I preached a sermon in the packed church, which we'd extended by knocking down the wall between the church and diningroom. The sealed coffin lay on a table in front of the altar. We had invited classes from other parts of the school to come, and I told the congregation about the journeys and possible fates of Paulo's soul, about the bliss of Heaven and the horrors of Hell. I reminded them that money given to the Church could alleviate Paulo's suffering, and told them about the Last Day of Judgement. At one stage, as I was describing what Paul might find in Hell, I noticed that some of the young kids from other classes were looking rather troubled. Later I mentioned this to one of their teachers, who arranged a comforting discussion back in their classroom afterwards.

At the end of the service, we stood around the grave, all except for Allen (who had his bugle) and the pallbearers. Then, to an hilariously out-of-tune funeral march, the coffin was brought out, forced into the grave (which turned out to be fractionally too narrow), and covered with earth.

The funeral was both great fun and somehow very serious. There were lots of suppressed giggles at times, but also some very silent moments. That afternoon, after we'd taken off our costumes and had become 1984 people once again, we sat around in the village square and talked about heaven and hell, about death and dying, Allen and I said very little during this discussion - it was mainly kids asking questions, or telling the group what they, their friends or family believed.

A month or two after the village had ended, a friend of one of the children in the class died tragically. Her mother wrote to me:

The village burial became sadly important to us when our friend died and his family chose a burial for him. We all had a lot of difficulty accepting the finality of this child's death, especially given the circumstances, and it was apparent that my younger children, who had both been at the village ceremony, were more comfortable in talking about burial than either their elder brother or myself. When directed-play can deal with themes which are connected with taboos, it becomes especially valuable.

Paul continued his life in the village as Don Carlos. He became one of the steward's right-hand men at the Manor Court meetings, where complaints about villagers were heard, and he later took over as leader of the crusade army's training. From being sceptical about the village and suffering the indignity of being replaced as the steward's servant even before the village had begun, he was now back in the centre of things, and had got there by a route entirely of his own making.

Food and Drink

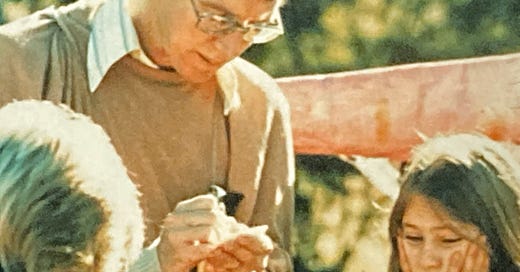

Just as in medieval times, much of our villagers' day-to-day life revolved around the production and consumption of food. Our village kitchen was a centre of activity on most days, and especially on our weekly market day, when none of our class was allowed to bring lunch from home, and when we invited kids from the rest of the school to buy our wares and sample our food. Liz, a parent, had now taken over Effie's work, and was based in the kitchen. She kept a diary during this period, and her writing captures the hustle and bustle of the village.

Tuesday 29 May

Incredible activity in the kitchen and competition for bench space and cookers. Anna and Tegan making soup, crying from the onions. Siobhan (with her mother) making cookies, Shelley making punch, Kate C. drops a bottle on the floor. Chris and Michael [Allen's nephew, who was visiting the school for a month] making chicken soup. Martha Higgins (Olivia) collects her ingredients and goes off to the ale house. Amy cooking mushrooms, Caitilin more French toast.

Amy's pastry is rusty from the crummy tart tins - Caitilin (who is village steward) threatens to fine her for selling rusty food. We think it better that she chucks them out. She is disappointed. However we rescue six. I promise to bring in my tart tins tomorrow. She looks very forlorn. I feel she has been crowded out.

I remember I have forgotten to fetch Rachel [Liz's daughter] pan to put her crumble in the oven and cook her rice. I didn't know the market started at 11.45. I thought it was 12.30. I persuade her there is time to cook rice. I fight for a ring on the cooker. The saucepan has no lid. Jennifer (Siobhan's mother) and I juggle things around in the oven. Kate cooks a lump of bread dough on the saucepan lid.

Suddenly it is time for market - now the real panic begins as the children realize there are no plates, cups, etc to serve things on. Someone finds some plastic beakers. Suddenly everyone is gone. I am left with the rice and Rachel and the problem of how to serve it. We only have an ice-cream scoop. I suggest using the egg box. She suddenly lights up and says, 'Why not use a paper cone, with a dollop of rice like an ice-cream cone?' She zooms off to find paper and tape, but it doesn't work, she is very down. I remember the plastic cups in the drama room. We use these.

We can't find a place in the village square to sell them. The atmosphere in the market very convincing - a great deal of shouting, noise, people shoving etc. Rachel sets up two chairs, she is very despondent, the competition is too much, no-one wants rice and the apple crumble is over-priced.

I suddenly panic about the kitchen, in case the ovens are left on. I find three monks - Matthew, Dan and Kleete - sitting round a pot of cold water with green spaghetti poking out. They are telling Matthew he should have broken it before he put it in. I am staggered that anyone could eat after the market. They explain about the monastic lunches. Steve comes in and asks me to help Matthew - he seems a bit shy and nervous (not like the Matthew I see playing outside with David etc). His answers are non-committal and short ('It's OK'). Dan and Kleete come back in to check how things are going. I don't know how they are going to eat it all - Kleete grins and claims to be a bottomless pit. When it is ready, we go up to the monastery with it to find no-one has laid the table and there is no cutlery back in the kitchen.

I now spend more time in the market. Lots of visitors from other parts of the school. Rachel is happy - her rice and crumble now in demand. I buy flowers and lavender bag from Rachel J. and Natasha - would like to buy more and spend more time looking, but I find it too noisy and only want to get away. It needs more space. [We set up the market place outside for subsequent market days.]

Back to the kitchen. Find two secondary boys washing and cleaning up. They have been hired by Martha Higgins and co. [the shepherd family, whose responsibility it was to clean the kitchen that day] so they can earn village money!

The other focal point for food and drink in our village was the ale house. It had been run for the first couple of weeks by Peter, Cameron and John, and on most days it had done good business. It was situated in one of our quiet rooms, a room with a sink in it, and the boys had built a counter with the cardboard bricks, separating the 'kitchen' area from the customers' lounge. Peter cooked at home, and the boys usually made Destiny cakes from a medieval recipe or pancakes each morning.

At the beginning of the new term, the ale house became the focal point of rivalry between the manor house and the monastery. Allen and I had talked privately about this. We thought some conflict might give kids like Anna, whose interest in the monastery was tempered by her suspicion that all the real action was taking place outside the monastery walls, a renewed interest. It might also give the village a political edge that would appeal to kids like Chris, Paul and Caitilin. And we both felt that a certain amount of economic rivalry between the manor house and the monastery would create employment and give those who needed it the focus of a steady job. So, not long into the new term, the monks decided to employ cooks, toy-makers, and clay workers to produce goods we could sell at market days, and we planned to use our new wealth to buy up as much of the village as we could, starting with the ale house.

I preached sermons about the greed of the Lord, while Allen and the manor house people made political speeches criticizing the monastery's wealth and worldliness. Letters were written to the Pope (Vaughan) and to the King (Bernie, no longer the mastercraftsman). The monastery put pressure on the Lord to sell the ale house, but, in the middle of what we felt were promising negotiations, he sold it to Chris and Michael, for one pound.

This rivalry between the monastery and manor house didn't ever have a big impact on the village. A few jobs were created, and Allen and I had fun making public attacks on each other. But it was essentially an adult idea, and some of the monks were rather critical of my attacks on the Lord. One of the kids told us afterwards that she'd been quite upset to see her two teachers arguing publicly.

But the rivalry did have meaning for Chris. He loved the manoeuvring and the intrigue, and once he had bought the ale house he worked very hard in it.

But where had he got the money to buy it? One pound was a lot in our village, more than someone could earn as a servant in the manor house. At the time, I concluded that Allen had given it to him for less than a pound just to foil the monastery's plans.

It was only after the village had ended that I learnt the truth. Mild-mannered Dan - the conscientious monk who spent each village day in the scriptorium copying out and illuminating dozens of signs, texts and pardons - this paragon of monastic virtue was in fact secretly in league with Chris, and was double-crossing the monastery. He had saved up a small fortune from his work as a stained-glass window maker and from sales of illuminations.

‘I got involved in the ale house after a while,' he told me, grinning widely at my disbelieving face. 'I wasn't allowed to, I know, it was against my nature because I was a monk. I helped Chris to buy it, and then I was getting profits out of it secretly.'

'Yeah,’ said Chris, who was with us while Dan told of his secret life in the village. ‘We bought it together, Dan, Michael and me. We'd been saving, and I suggested the idea to Dan, and Dan thought, "Rightiho, this is good, who wants to be a boring old monk, we might as well have something on the side to keep us all going ..."'

'I got big profits out of it,' added Dan. The only thing I didn't like was the washing up. There were too many glasses, so we employed people at extremely high wages to wash up for us. Sometimes we offered free drinks to people who washed up. Sometimes you'd get a few desperate people who were really poor.'

Anna, too, found herself working in the ale house. She'd missed a few days of school that term through illness, and being out of touch had exacerbated her difficulties as Abbott. Also, it was hard for her having me as the Prior, especially when some of her own ideas didn't get my support, such as her wish to send monks off to join a crusade army to be trained by Don Carlos at a time when I felt they were just settling into the monastery. In the end, she wrote to the Pope requesting permission to leave the Order, and, when she didn't get a reply immediately, she and Jenna went dancing in the village square, causing something of a scandal and hastening up the process somewhat. She was released from her vows, and went to work in the ale house. She got married to one of the village women, and they adopted Chris as their son.

While intrigue, double-crossing, money-making and their new roles were occupying the minds of Anna, Chris, Paul and Dan at this time, the rest of the village continued its daily life, as Liz recorded in her diary.

Thursday 31 May

David B. wants to cook but has no ingredients. I sort through what there is, and do a bit of buying from other kids. We decide on pancakes - no recipe, no measuring equipment. We make a pancake mixture, but something is wrong. We put in another egg, but they're still not working. He is beginning to get anxious. I find a cookbook and decide they must need more flour. I tell him how to get the flour in by mixing the original batter into some more flour, rather than lobbing in the flour. He does it without any help. This time the pancakes work. He is confident and soon starts tossing them.

Katherine and Anicca watch Peter making Destiny cakes and ask him questions. I like that. Shaun, who hadn't done his cleaning up yesterday, reports for duty. I send him off to find some window cleaner. He's gone for about 45 minutes, but comes back with some. He squirts it all over the outsides of the windows.

Inside I am now making cardamom cakes with Matthew. He seems happier today. I read the instructions out one step at a time. He follows them. Again, a lot of guesswork on my part measuring the ingredients.

Shaun now doing the inside window. He accidently kicks over Caitilin's eggs - one breaks on the floor. He cleans it up with his window cleaner. Windows seem dirtier rather than cleaner, but he's really nice to me. I tell him they are terrific and he is forgiven. He runs off shouting, ‘I'm forgiven! I'm forgiven!'

Matthew now has a tray of cakes to go into the oven. They look super. He is pleased and sings the Peter Russell Clark song. The cakes look wonderful cooked. They have risen and joined together like hot cross buns. We show off to Sir Edmund (Allen) who has just come in. He tries to persuade Matthew to leave the monastery and join the manor house, but Matthew says no. We find a wooden plate and he goes off to sell them for one penny each. He was going to sell them for two a penny, but that was definitely underpriced. He never comes back to wash his cooking tray.

I watched the girls dancing round the may pole in their lunchtime. I also talked to David S. and Shaun about the clay birds they've been making. David is holding his as if it's alive. He tells me they are eagles. Shaun tells me that he and David only recently discovered his talent. I love one particular bird of David's. I am very moved by it, it nearly makes me weep. He's really put part of himself into the clay. I want to buy it, hope he remembers. The bird is tucking its head beneath an outstretched wing.

I ask Rachel if she knew that Martha Higgins [Olivia] had a baby. Rachel says she had it six times! Martha pulled it [a doll] out the first time, then Rachel had a go, and then the doctor finally made it.

For each market day, the Lord would appoint two families to cook a meal for all the villagers. The families would meet with Liz to plan.

Monday 4 June

I meet with the big shepherd family and Allen in the village square, to talk about food for market day. Olivia has plans for pikelets and cakes, but Allen says no, it must be a main course. I suggest things they can cook in the oven - potato cakes, quiche, spinach pie. Decide on cornish pasties and soup. Olivia goes off to the library for a cookbook. I stay with Jessie, Clare and Tom and my recipe book. The recipe is for sixteen, so we decide to quadruple it. We make a list of ingredients and quantities, and they go off.

Back to the kitchen. Matthew singing again, making Destiny cakes today. Mike wants to make something different. I suggest drop scones, he wants to make pancakes. I find the recipe. I try to do the accounts and ignore everything else. I give Mike distracted instructions. His first pancake a disaster, his second one goes on the floor. The third one awful. I give up and decide to show him how to get more flour into the mixture without making it lumpy.

The steward [Caitilin] comes into the kitchen. Mike and Kleete try to get her to taste the failed pancakes. (They are awful. I tasted one. Slime in a burnt case.) She is naturally suspicious, very much in character. She threatens all of of them - Mike, Kleete and Matthew - with the Manor Court - instant fines for attempting to bribe her, refusing to sell her goods that should be on sale [i.e. Matthew's Destiny cakes] and possibly attempting to poison her [Mike's pancakes].

Back to Mike's pancakes. I show him how to heat the oil, then how to move the pan and make a thin pancake. After this he is OK. He is really pleased when they work. He sells one to Shelley and one to Kleete. He's pretty tired by now, and wants to get out. He washes up after a fashion.

Go into Damien's hut outside - freezing out there. Damien asks me for a black pen to make a scar on his face. I ask him how he got it - out hunting? Damien says no, he was attacked by robbers and thrown off a cliff. Later on in the day I have a maths session with him. I try to work out how much we took last week, how much I owe for rent, how much I should pay him as my assistant. Finally decide on six pennies for rent, one tenth of my takings for him. I've taken seventeen shillings and six pennies. He worked out that he gets one out of the ten shillings, leaving seven shillings and six pennies. He wants the answer to be one shilling and six pennies, but knows that this is not right. I suggest we change the seven shillings into pennies before we divide it by ten. I explain it twice before he gets it.

The Village Marriages

There had been an undercurrent of anticipation ever since David and Anna R.'s brief engagement. Rumours were rife, more negotiations were entered into, but, for a week or so, no-one was game enough to take the plunge.

Rachel was one of the steward's cousins in the manor house. She was ten at the time, and had an apparent air of indifference which masked a deeper sensitivity. She was thin and elegant, with large blue-green eyes and fine hair which, in the village, she usually wore drawn back from her face. She was involved in several of these tentative negotiations, as she told me after the village had ended:

Quite soon after the beginning of second term, Jessie asked me if I would marry her. But I wasn't ready for marriage, I wanted to stay single. Amy was my grandmother in the village, and I asked her for advice, and she thought I shouldn't get married because I hardly knew Jessie. So I didn't.

About a week after that, I was walking outside when Gunnel came up to me.

'Did you know that Mark the blacksmith wants to marry you?' she asked.

‘First I've heard about it,' I told her.

‘Well, it's true,' she said. I realized that she was some kind of messenger. 'What do you think?'

'I don't know. I'll think about it.'

Then Rachael J. came up to me and asked, 'Is it true that you and Mark are going to get married?'

‘I don't know yet. I'm thinking about it.'

‘Well, she said, 'if you decide not to, then I want to marry him, and I think he'll marry me.'

I thought about it that night, and I talked to the other nobles the next morning. They told me, 'You're a noble! You can't marry a blacksmith!' I went over to the blacksmith's house when no-one was around and checked it over, but I didn't like the look of it - it was too much like a chook house. So I told Mark that I'd decided not to marry him.

By then there was a lot of excitement about marriages in the village, like I remember Paul standing outside his cottage and calling out, 'Who wants to marry me? If you want to marry me, then come here!' and some of the younger girls went rushing over to him.

Paul himself remembers the beginnings of his interest in a marriage differently:

Anna's shepherd family was rich, and Dave said to me, ‘Why don't you marry, Anna?'

'But she was going to marry you,' I said. 'She can't marry me! You can't marry our son's supposedly wife. Anyway, she's too young!'

But he convinced me, and I can remember coming up to you, Steve, and saying 'We want to get married,' and, while we were talking, Anna ran in all excited and said, ‘My mother and father say yes.'

Before all this I'd talked to Allen, and said, 'Allen, I have to get permission from you as being Lord, if I can get married,' and he said ‘Have you asked her?' and I said, No, I'll just ask her parents or something,' but he arranged for a meeting between the two of us and I had to ask her there, and she said yes.

I can remember that Anna's real mother came to visit the school that day, and she came up to me and said, 'Are you the young nice boy who is marrying my daughter?' It was so embarrassing!

Now that the ice had been broken, events moved quickly. Mark was discussing marriage with three separate girls at once. I was asked by two girls to visit each cottage in turn, to look for any boy who was willing to marry either of them. And Catriona (whose village name was Richard) had to sign the following letter before her (his?) father would let him marry:

Hereby I, Richard Charleson, agree with my parents that even after marriage I will tend to my chores:

Chopping the wood

Lighting the morning fire

And looking after and helping my parents in times of trouble e.g. poor, sick or old.After I have signed this document, I can not go back against my word.

Signed,

Richard Charleson

At this time we had a new boy in the class. Michael was Allen’s nephew, and was visiting Canberra for a month. He joined us at school for the village, took the part of a noble, became a friend of Chris's, and helped Chris to buy the ale house. He was now living, with Chris, in the ale house. Again Rachel takes up the story:

A couple of the nobles, especially Caitilin and Gunnel, encouraged me to marry Michael. They talked to Michael, too, and he said that he'd think about it that night. Well, the next morning, I went into the ale house and Michael was there.

'Caitilin talked to me yesterday,' he said to me, 'and she said that you might be interested in marriage. So I thought about it last night and decided I want to.'

'OK,' I said. 'Where do you want to live?'

'Here in the ale house, ' he said. ‘This is my home now, cos we own it.'

‘I don't want to live in this place. I'm going to live in the manor house!' I didn't want to move because that's where my friends and my own space were.

‘Well,' he said. ‘If I move, then Chris will have to come too.’

'But we can't have Chris! He doesn't belong there! You're related to the Lord, but he's just a common person.'

"Oh well,' he said after a bit. 'I guess that would be OK. I'll move into the manor house.'

We didn't talk together any more that day. But I had some hassles with Allen about money. Nina was a noble and she'd got married about a week before, and Allen had given her a lot of money as a present. But he wouldn't give me any - not much, anyway. I said that it was unfair, I was pretty upset, but he said that he was running out of money.

The next day, Ra and Shelley came to see me. They wanted to have their wedding with ours, because it would be cheaper that way. I said that I'd talk with Michael, but he wanted just a single wedding. 'Well I want to get married with them,' I told him. 'You should pay for the wedding because you're the man, but I know you haven't got much money. So I'll pay, but I want a cheaper wedding.' So he agreed.

I didn't really know whether I wanted to go through with it, but everyone else was keen for us to get married. And I knew that there were only two weeks of the village left, so I thought to myself, ‘Well, if I hate it, it won't matter all that much.'

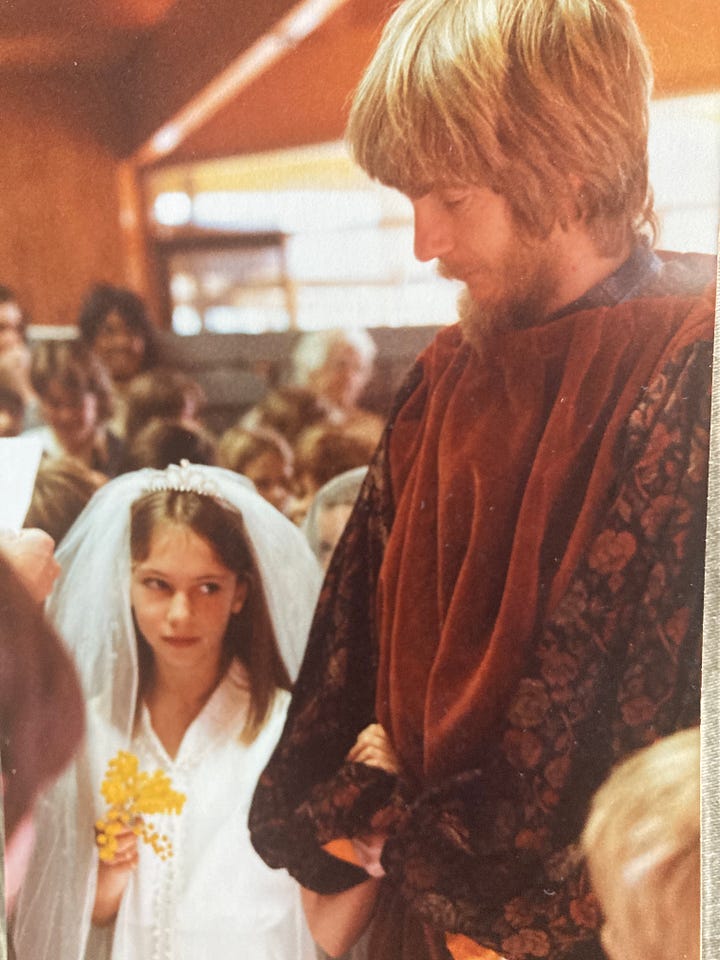

Paul and Anna came to see me in the monastery soon after their decision to marry, to discuss the wedding service and agree on a marriage fee.

‘What's all this about "for richer, for poorer"?' asked Paul. ‘And "till death us do part"?'

‘They mean,' I said, pointing to the relevant section in the litany, ‘that no matter what happens, whether things turn out well or badly for the two of you, as far as God and the Church are concerned you are married until one of you dies.'

'But why do I have to promise to obey Paul when he doesn't have to promise to obey me?'

Again I put the medieval Church's point of view, and was rather disappointed that she seemed quite content to accept this. I had expected these weddings to generate discussion in the group about medieval and contemporary views on gender roles, and perhaps this kind of discussion took place in the children's real homes. But there was very little of it at school, and, on the occasions when I raised it myself outside village hours, I sensed a resistance from the children - not in the form of disagreement, but a feeling that these were issues they didn't want to discuss at that moment. The children seemed too involved in the role play, possibly unconsciously wanting to experience some of the fantasy around marriage before stepping back and looking at it more objectively. They were also clearly immersed in their own developing interest in sexuality, and the village was providing a safe environment for this exploration.

After their meeting with me, Paul and Anna sat on a bench in the church and made some arrangements of their own.

"Where are we going to live?' said Paul, to himself as much as to Anna. 'The gypsy house is too small, especially now that Kate has got married and Nina has moved in with him. And I can't kick Dave out.'

‘I could ask my family if we could move in there?'

'No, I don't want to leave the gypsy house.'

‘Why don't you build some kind of extension,' I suggested from my side of the church. ‘The monastery has some spare bricks you could buy.'

They looked at the bricks, then went out for five minutes to see how they might extend the gypsy house.

'Yeah, we'll take them,' said Paul.

‘Who's going to pay the three shillings for the ceremony, and the money for the bricks?' asked Anna.

‘Well your family said they'd pay a shilling,' said Paul. 'But I'm going to have to borrow, I think.'

The two of them made the guest list for the post-wedding party, and organized the food. Paul made most of the decisions, but whether this was because he was Paul, a boy, older than Anna, or they were playing out their medieval roles, I wasn't sure.

Rachel and Michael had their arrangements to make too.

For a couple of days before the wedding, Michael would phone me up at home. We weren't sure what to do about a dowry, whether he had to give me some money or something. He told me that he was making a ring at home, but when he brought it in to school it was much too big for me because he'd used his own finger as a model for it. We took it to Anna the jeweller, and she bent it to make it smaller, but it went all lumpy. I wore the ring till the end of the village.

Mum and I made a dress and a tiara at home, and one night just before the wedding the whole family including Dad tried them on.

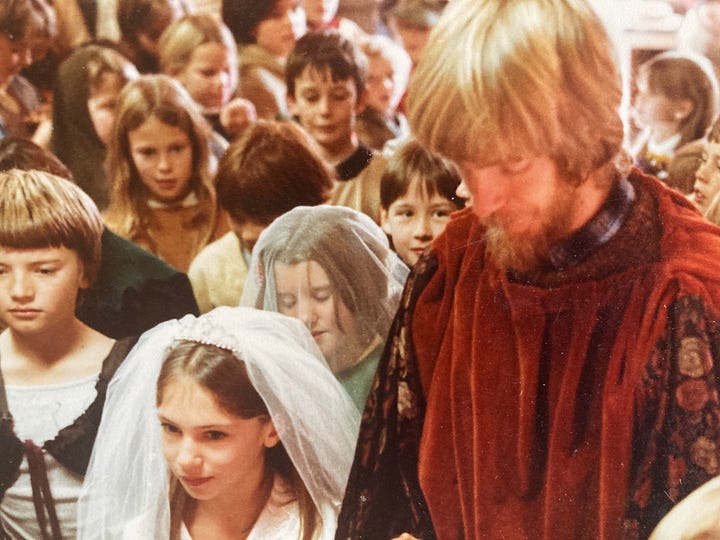

Then on the morning of the wedding, we got the food ready, got dressed up and waited outside the church while the rest of the villagers took their places inside. There were eight of us there, all getting married at once. Tegan had a bright green dress on, and someone said to her, 'Hey, that's not medieval!’ ‘I know,' she said. ‘But I like it!' And she told David that she wasn't going to marry him unless he got more dressed up than he was.

As we walked into the church, I had this feeling of being unready for it. Then you, Steve, started talking, and you went on and on, and someone behind me said quietly.

'God, shut up Steve!' We wanted to put you onto fast forward.

The feasts which followed each wedding were planned days ahead. The food was prepared by the children themselves, and presents were exchanged. For some of the weddings, invitations were sent out, and for others (including Rachel and Michael) the whole village was invited to the service and feast. Mark made a three-tiered cake for his wedding party, and medieval music was played from a hidden tape recorder.

About twenty of our forty-eight children were married in the village, and almost all the kids were caught up by the excitement these weddings generated - the family conferences, the proposals, the preparations, the ceremonies and the wedding parties.

Fair and Feast

After school on the day of Paul and Anna's wedding, Allen came and sat next to me on the stairs in our classroom, and we talked for a little while about the kids' solemn faces as they made their vows and exchanged rings.

‘Well,’ he said after a few minutes, ‘when do you think we should finish?'

For a moment I wasn't sure what he was talking about. I had become very involved in the project, and was enjoying presiding over the village weddings.

‘The village, I mean,' he said when he saw my blank look. ‘When do you think we should wind it all up?'

‘Oh, I don't know,' I said vaguely. ‘These weddings are pretty important at the moment, and the new couples will want to have time to explore their new life together.'

‘Well, I think we should start thinking about winding down now,' said Allen.

‘Do you think that kids are getting sick of it?’ I asked.

‘No. There are a few kids who are finding it hard, but I can see that most are still involved. The funeral was great, and the weddings are obviously important to quite a few. But I do think that some of the kids are finding this business of staying in role, having another character, hard to maintain.'

It was true that kids were starting to use real names rather than village names, and that a few were no longer wearing their costumes. On the other hand, these weddings could lead to new and interesting possibilities, I thought. What would happen, for example, if a marriage failed and the couple wanted to separate?

Allen, though, insisted that it was time to wind down, and this made me feel uneasy. Had I become too caught up in the project to be able to see it clearly? The thoughts that had been swimming round in my head at the time of the parent letter had been submerged by the excitement of village life. But Allen's remarks brought some of them back. Were we just having fun now? Were the kids actually gaining from what we were doing? Or was I letting my own love of role play and fantasy carry me away from the real needs of these children?

'Let's talk about it with the kids tomorrow,' I suggested, 'and see what they've got to say.

At our meeting the following morning, it became clear to me that Allen was right. Despite a spirited argument from a substantial minority that we continue the village indefinitely, most were ready to discuss an appropriate way of finishing, and we agreed that, two weeks hence, the village would end with a fair, to be held on a Sunday so that families could attend. Middleton's final fortnight revolved around the kids' preparations for this event.

Under Allen's supervision, a group of village labourers worked outside to prepare the fairground. To define the boundaries of the market place they stretched ropes in the shape of a large semicircle between trees, from which stall-holders would later drape their banners. They also built a set of stocks, and painted them with garish red and yellow stripes, suggesting perhaps that some had had enough of being authentically medieval. A horizontal pole was erected a metre off the ground, on which rival villagers could do battle with pillows. And they built a contraption for jousting practice, modelled on a picture we'd seen in a book on medieval children's games. Two poles were joined in a T-shape, and set in a hole in the ground. A timber shield dangled from one end of the crossbar, and a sack filled with straw hung from the other. I watched one morning as Paul charged at the shield with a lance, only to have the sack swing around at the impact and whollup him on the backside.

Inside, Liz worked with the villagers who planned to sell goods at the fair. Most of the food was prepared and cooked at home, leaving Liz free to set up a craft workshop, equipped with needles, threads, scissors, adhesives, paints, candle-making apparatus, and various other odds and ends. This was where Anna spent the final stage of the village, painstakingly making painted cloth toys, including a large stuffed 'icecream cone with chocolate and strawberry topping'. She and her friend Caitilin spent several hours one morning designing and painting a large banner for their stall.

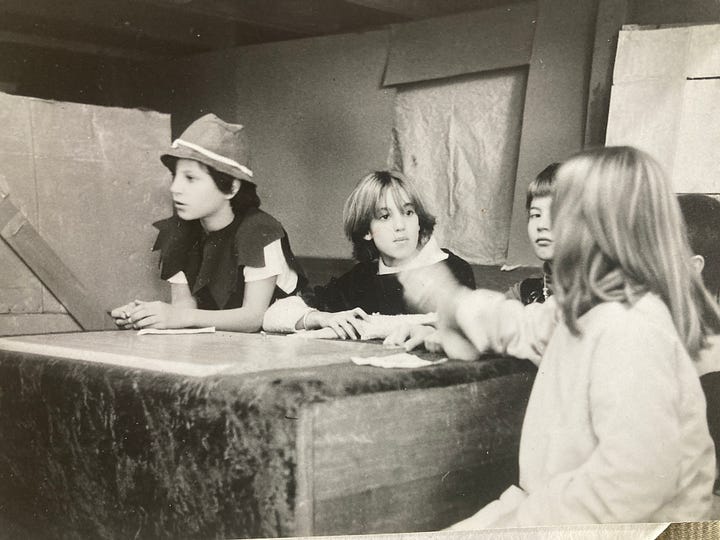

I worked with two groups, one (which included Dan and Chris) practising various three and four-part medieval recorder and percussion pieces, and another putting together an improvised play on the Seven Deadly Sins. Chris beat Paul in a vote for the main part, that of Satan. Paul was clearly disappointed about this, but threw himself into the part of Satan's offsider with such gusto and talent that he ended up stealing the show anyway. Dan played the part of the quiet monk who unexpectedly commits the sin of Disobedience by opposing the Abbott's will. It was the first speaking part he'd taken in any of our class plays.

During non-rehearsal times, Paul trained a small band of crusaders, who were to be presented to the King on the day of the fair. They ran laps to get fit, and fought and marched under his watchful eye. It was more light-hearted and less controlled than his earlier army.

On Friday 22 June, the kids set up their stalls, and we went through our final rehearsals. During the weekend, there was more last-minute work done in the kids' homes, and then on Sunday, it was fair day.

The fair ground was decorated with a dozen or so brightly painted banners above a semi-circle of tables laden with cakes, candles, biscuits, soft toys, embroidered handkerchiefs, multi-coloured wax candles, drinks, iron pokers and door handles, clay animals and jewellery. Matthew and David had arrived at seven a.m. to cook a spit roast, and by 9.30 when the rest of the families began arriving I could hear the meat crackling and smell its rich aroma.

‘We've got problems at the bank,' said Jamie to me before the fair had begun. 'We haven't got enough village money left to exchange the parents' dollars and cents.'

Allen and I quickly decided to change the exchange rate, not realizing until too late that this meant that the kids' carefully printed price tags were now useless and had to be hastily redone.

The bugle sounded a fanfare, and the King (Bernie) arrived, wearing a full-length green gown and jewelled (cardboard) crown. He presented a pound to Cameron for some unrecognized and unrecompensed work he'd done in the village, and then inspected Paul's well-drilled crusaders. The fair was then officially declared open, and for the next couple of hours the stallkeepers touted their wares while musicians busked, offenders (and volunteers) were pelted in the stocks with wet sponges, the meat was served, villagers knocked each other off the pole with pillows, and potential knights (and parents) jousted. At a special sitting of the Manor Court, complaints were laid by several villagers about the disgraceful and divisive rivalry between the Lord (Allen) and the Prior (me), and we were sentenced to settle the dispute with pillows. Finally the villagers performed the Seven Deadly Sins play, the climax of which came when Kate threw a specially baked cream cake into Paul's face.

Then everyone went home to rest before the feast.

When we got back at about six p.m., the parents had transformed the school's drama room. Tables were set and decorated with flowers and leaves, and menus were printed and individually named. The parents waited in costume, ready to serve at the tables. And the whole scene flickered in the soft light of dozens of candles.

The villagers and monks assembled outside, and a parent-led music group began to play a march. As each villager walked to the tables, his or her village name was announced by a costumed doorman. There were about five courses, interspersed with speeches and music, and a very solemn knighting by the King of a squire (Andrew) who had passed all the necessary tests. We finished with a dance.

My memories of the meal are hazy. Though most of the kids were thoroughly enjoying the atmosphere and the ceremony, I was suddenly aware that I was exhausted.

After the kids had gone home, Allen and I helped clear tables and chairs out of the drama room. We walked along the path in the dark, laden with chairs.

‘I guess we'll have to decide tomorrow whether or not to dismantle the village,' I said.

‘What?' said Allen. He stopped walking and put down his chairs.

‘The village, we'll have to work out whether or not to take it down tomorrow.'

'Are you serious, Steve?' asked Allen incredulously. 'It's got to come down! We've got to end this village properly. If we leave it standing, we'll never be able to get on to the next part of the year.'

'But we wouldn't have to take it all down to make the room feel different,' I said. 'I like the way we've made sound-proofed private spaces. If the kids just painted the walls their own bright colours, then we'd have ready-made private work areas.'

'Are you sure you're not finding this village just a bit hard to let go of?' said Allen.

'No, I don't think so. It's just that I like the idea of all the private spaces.' I could hear my voice sounding defensive.

Reluctantly Allen agreed that we should put the problem to the kids in the morning, and when he arrived at school he found me at the board, writing up my side of the argument.

'Have you left me any room?' he asked, only half in jest.

The children sided with Allen, and we spent the day dismantling the village, though we stored the best bricks in our quiet room to use later on for private spaces. And that afternoon we completed the death ritual by burning the rest of the bricks in a large bonfire outside.

It was both the end, and not the end.

There is a hill at the back of the school, and the grass had grown long there. At lunchtimes and before school for about two weeks after the village was taken down, groups of children from our class went up on the hill, made grass villages, and gave themselves new roles. There were monks and kings, soldiers and spies.

I am in another village called Mousey Village [wrote Eli] and I'm really enjoying it, and I'm a monk. But today some of the village got destroyed. Three and a half huts weren't there anymore, and nor was our god, who was a dead mouse.

The kindergarten children at the school decided to make their own village, and Anna (who was a great favourite with the five-year-olds) and some of her friends spent a couple of days helping them, using some of our bricks. Margaret, their teacher, told me afterwards how sensitively these older children had helped the young ones work on their five-year-old ideas, instead of imposing more mature plans on them. As Margaret talked, I thought again of the turtle.

And in our own classroom we settled back into a quieter routine. Both Allen and I were deeply tired, not so much from long hours or hard physical work as from the tension and excitement that came from following a path that neither of us had trod before, unsure of where it would take us and what we'd encounter on the way.

And, along with the tiredness, I felt immensely relieved that we'd made it to the end.