Part 2 Chapter 4: Building the village and making the rules

From my book 'School Portrait' (McPhee Gribble/Penguin, 1987)

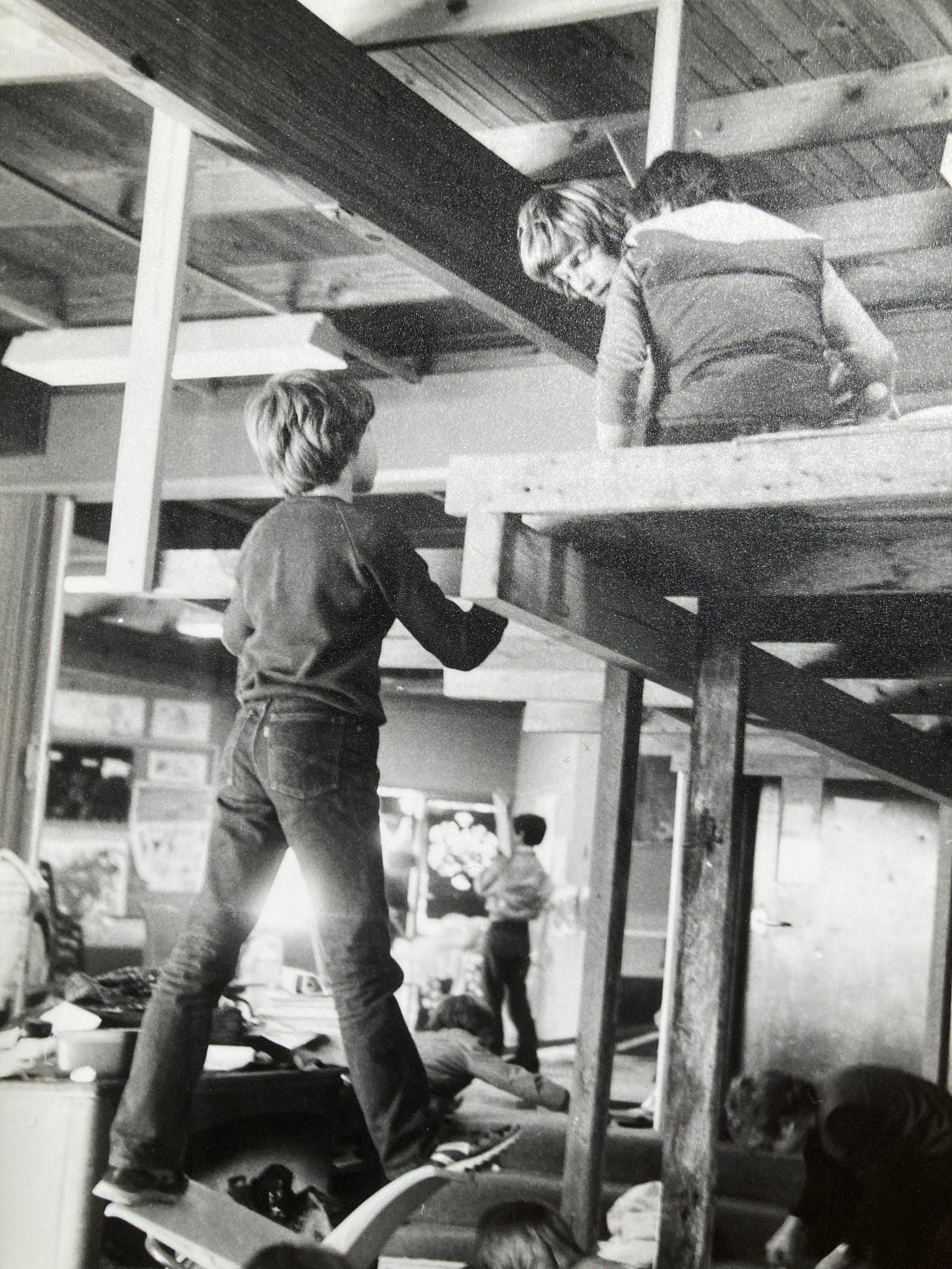

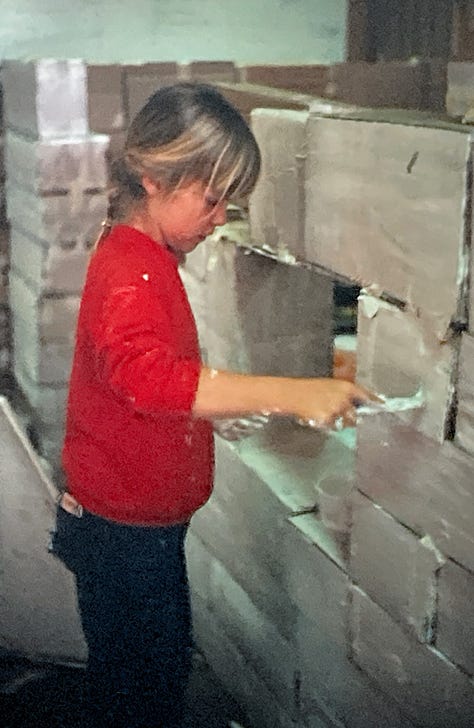

We were now ready to make the bricks and build the village. During a weekend in mid-April, the children brought their parents into a classroom empty but for a mountain of cardboard sheets, and, for about ten hours on each of the days, we cut, folded and taped the bricks together, while Allen and some of the nobles erected the two-storied timber frame for the manor house. It was tedious work, and nobody much enjoyed it, but we were spurred on by our target of four thousand bricks.

But by the end of the weekend, we had just over two thousand bricks, and so we had to modify the plan that had cost us so much the week before. On Sunday evening, Allen and I worked out some alternative ways to build the village without departing radically from the agreed layout. 'It'll be a great maths exercise,' said one of the parents when we told him about the alternatives we were planning to present to the kids the following day, and I thought about his comment that night. We didn't do projects like this because it helped the kids with their maths, just as we didn't play music just because it gave the children a better sense of rhythm. But experience with numbers and maths concepts was certainly one of its by-products, whether they were working on brick totals, making model cottages, talking about percentages with Bernie, calculating taxes, preparing for market days or paying wages.

On Monday morning the kids were impatient to begin building, and quickly agreed to a plan which reduced the height of the village and had the manor house walls made out of sheets of three-ply instead of cardboard bricks. The amended village was still as shown on the map in the last chapter.

'OK, one last thing,' I said to the kids, who were itching to start building. 'It's very important that you don't rush your work. If you build carefully, your cottage will be surprisingly strong. If you don't you could feel disappointed when walls start to sag or doors cave in. So there's a process here that I'm insisting on. First you put out your first layer of bricks, without glueing them together, and you call me. I check to see that they're OK, and then you can glue them together. Then you call me again, and I check your glueing. If your work passes, then you can lay out your second layer for me to inspect. And so on. If any group rushes ahead and misses an inspection, it runs the risk of having to dismantle what's been built. Right, you can go off and do your first layers.'

During the final days of the week before, and again during the weekend, there had been periods of genuine weariness amongst the kids. But now the atmosphere in the room changed dramatically. There were smiling, alive faces everywhere, some singing or calling good-naturedly to friends as they collected bricks and laid them out in careful straight lines.

‘I'll get the scriptorium bricks, Kleete,' called Dan. 'You get some glue and I'll meet you there!'

'Come on Jessie, you work with us,' said Anna as she and Jenna loaded themselves up with bricks. ‘Will we start with the Abbott's house or what?'

I drew up a quick chart so that I could keep track of the inspecting.

'Over here, Steve,' shouted Anna, ‘we're ready with the first layer of the monastery.'

The monastery kids had got together with Anna the jeweller, and had decided to put out the first layer of the whole building, rather than do it room by room. I went over to them.

"Well, the bricks look OK,' I said. 'Are you happy with the sizes of the rooms?' They nodded. 'What about doors? I can't see any gaps for doors.'

'Oops,' said Dan, and monks scattered to different parts of the monastery to take out bricks for doors. Finally they were ready to glue their bricks together, and I rushed off to check the bakers' first layer.

All around me there was the bustle of purposeful activity, and it reminded me of the scenes in some of the drawings Allen had shown us of a medieval cathedral's building site. With columns of precariously balanced cardboard bricks in their arms, children moved slowly from the huge stockpile in our top wet area to the site of their cottage, where others carefully built their walls. The gypsies were measuring and sawing planks outside for the frame of their small two-roomed cottage. Allen, Rachel, Nina and Gunnel were making an upstairs floor for the manor house from unused room dividers, while Ra, Caitilin and Amy nailed three-ply walls to the timber frame. Nina called down to me, 'Hey Steve, look up here! It's great isn't it! You should see the view.? I was surprised by just how quickly our classrooms were being transformed.

‘We're ready for the second layer,' said Kleete, and I hurried off to the monastery to inspect

.

About an hour later, I heard someone swearing outside the door. 'Shit, have a look at this will you!' Paul called to Kate. He swept his hat off his head, and threw it dramatically on the ground. ‘It won’t bloody fit!’

I went to see what the trouble was. They were standing with smiles on their faces and hands on hips, with their finished timber frame standing at the door. It wouldn't fit through the classroom door.

'Come on, you guys,' said Paul with good-humoured resignation in his voice. ‘We're going to have to take the bloody thing apart, and assemble it again inside. How dumb can you be.' They laughed, picked up the frame, and took it back to their working spot.

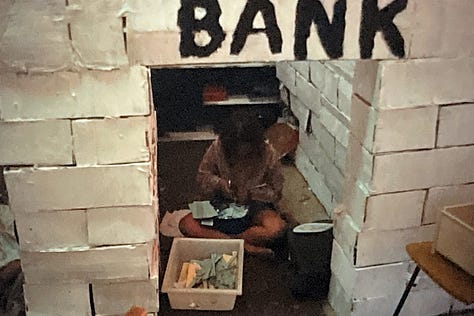

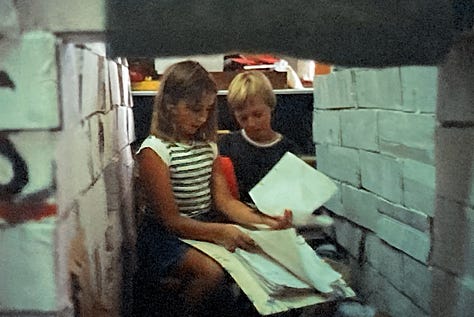

It took four busy days to build the village. At first the room was full of the banging of hammers, the whine of Allen's electric saw and the smell of dust and glue. But the hollow cardboard bricks acted as sound barriers, and the room's acoustics became strangely muffled as the walls got higher. By Tuesday afternoon most of the walls were finished, creating a network of alleyways between the houses. The manor house builders had finished the walls of the ground floor, and were now cutting windows out of the grey sheet cardboard walls upstairs. The gypsy frame had been dismantled, carried inside and rebuilt, and was now supporting a flat cardboard roof and sturdy brick walls. The big shepherd family had a quiet room for their cottage, and so had no building to do. Instead they used the time to put hessian round the walls, bring straw in for the floor, and had decorated and furnished their cottage with logs, plates, cutlery and a cellophane fire. By Wednesday the smell of glue had been replaced by the stronger smell of paint, all of it shades of brown and grey approved by the kids at an earlier meeting. By Thursday afternoon, we had a village.

I walked through the monastery just after it had been painted a rich dark grey. Anna was writing at a table in the Abbott's house, and I looked over her shoulder. She was making a sign for her door, and it said:

ABBOTTS HOWS

NOK BIFOR YOU ENTA

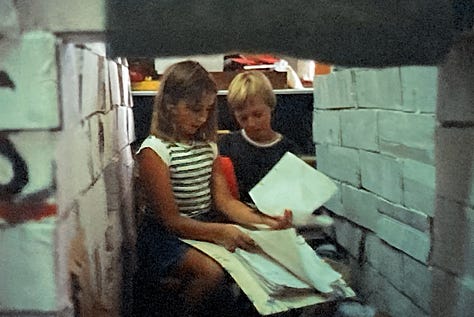

I left her to her work, and went down the new corridor, past the infirmary and into the dining room and the church. I looked through the doorway of the scriptorium, where Dan and Kleete were setting up their pens and paper and had cut a hole in one of the bricks for their precious inks and money.

‘Pretty good, eh,' I said.

'It's great, said Kleete. 'I really didn't think it would turn out as good as this.'

I wandered out, past the gypsies' shack. There were muffled voices coming from inside.

‘Can I come in?' I called at the door. Because of its ceiling, which made the interior dark and somehow secretive, I couldn't look over their walls into their rooms, as I could with other cottages.

'What do you want?' a voice asked.

'It's me, Steve,' I said. ‘I just want to see how it looks in there.'

'Come in.'

I could just make out Paul in the dark, sitting on a cushion in one of the tiny rooms inside.

What do you think?' I asked. 'How does it feel to have it done?'

'Great,' he said happily. 'It just feels like ours. I mean, no-one else can go in here. We own it, we made it, and no-one else can touch it.'

That afternoon, we sat in the village square and looked around at what we'd built. We had a two-storied manor house with arched windows and balcony overlooking the village square. There were strongly built cottages all around, for the reeve's family, the bakers, the two shepherd families; a jewellers, an ale house and a gypsy shack. We had a monastery with an imposing arched entrance and dark passageways leading to its many rooms. Outside, the blacksmiths had finished their timber loft, their forge was ready for action, and Damien had built his cottage. Only the animal enclosure was unfinished.

We felt a mixture of emotions - relieved, that the building and painting was behind us; possessive, about the private and individual spaces that we had created for ourselves; excited, that village life would soon begin in earnest; and proud, that we had managed to build something that had the appearance and atmosphere of a real village. It hadn't all been fun. There had been boring times, and there'd been some stress. It hadn't been easy. But it was real.

There were questions, too, buzzing around in my head as I looked to the days ahead. Would this strange mixture of fantasy and reality work? Would the children be able to distinguish between, for example, Anna their classmate and the tyrannical Abbott? Was the co-operative and creative community that Allen and I were working towards compatible with the make-believe which gave the kids 'permission' to act out feelings connected with power, violence, authority, and wealth? Did we adults need to organize jobs, to give a structure to those without ideas of their own, or would this discourage kids from thinking for themselves? Would the commercial side of the village encourage the constructive or the acquisitive sides in us?

We spent the next half an hour discussing a name for the village, and finally decided on Middleton. It had the right sound, the majority of kids thought, and one suggested that it was the abbreviated form of ‘Town in the middle of a deep and dense forest'.

Before school the following morning, Friday, I showed Allen a draft of some village rules which he and I had been discussing, and which we now planned to look at with the kids.

'I suggest,' I said, 'that we get each family to appoint a couple of representatives to discuss the rules, while the rest put finishing touches to houses and get ready for the start of the village.'

Allen looked uncertain.

'Do you think we should all do this together?' I asked.

‘Well, I agree that it's going to be difficult, particularly for some of the younger kids. It's going to take hours, I know. But I think it is important that we take this step together.'

I didn't like the idea of us all having another demanding day. ‘We've worked hard to get to this point,' I said to Allen, 'and I think the group needs a breather. A day-long whole group discussion would be asking too much of them.'

'Maybe,' said Allen, 'but I reckon that's a risk we've got to take. Otherwise those who discuss the rules will have a different feeling about the village, a different perspective from the rest of the group. The rules will mean more to them. No, I feel pretty strongly that it's something we all have to do together.'

I wasn't convinced, but I'd had cause to trust his instincts in the past. So we collected the kids together in the village square at the beginning of the morning, and handed each a copy of the proposed village rules.

PROPOSED RULES OF THE VILLAGE

As much as possible, the village will operate as a medieval village. Villagers will have to earn their money, and families will have to face the consequences if they cannot earn enough to pay for their food, clothing, shelter, taxes and rent.

All the buildings except the monastery are owned by the Lord, and rent must be paid to the Lord. The Lord or steward will decide the amount of rent that each village family will have to pay.

The Lord or the steward may evict any villager from his/her cottage, shop or workshop, and he may rent it out to someone else.

However, if a villager can save up enough money, he or she can buy a cottage from the Lord, at a price agreed to by both. From then on, the Lord (or steward) does not collect any rent for that cottage, and cannot evict the villager.

A villager who has bought his cottage, shop or workshop is free to sell it to anyone else, at a price agreed

Villagers (and the Lord and steward) will have to pay taxes to the monastery.

Any disputes that cannot be solved by the villagers will be settled by the Lord or steward at a Manor Court.

If anyone wants to change their job in the village, they can

(a) try to find another job in the village,

(b) become a poor person, who is cared for by the monks.Some villagers have asked if they can be thieves. We should all remember that

(a) villagers have worked for their money, and they've made or paid for the things they own. These villagers are going to be genuinely upset if these are stolen.

(b) medieval punishments for thieves were harsh. Thieves risk having their money, goods and freedom taken from them if they are caught.

(c) medieval people believed that the souls of the wicked would go to Hell when they died.

(d) our village will not be a happy one if there is mistrust and suspicion in it. The only way to get rid of the Lord is to buy the village and manor house from him, or by a peasants' revolt.

The Lord may declare boon days, where peasants work for him.

On Tuesdays of every week, all the food eaten in the village (including lunch) must be made in the village.

The village will run from 9.30 to 12.30 every day until we finish it. The reeve will inspect the whole village (except the monastery) at 1.25 pm, to make sure that houses (inside and out) are tidy.

All supplies should be ordered from the travelling salewoman [Effie] the day before they are needed. If you buy or use something that you get from home or the real shops, you should tell Effie or Allen or Steve, and pay Effie some village money for it.

I read out the entire list first, and then we went through each rule in turn, discussing it and voting on whether to accept, change or reject it. Some passed with virtually no discussion, and many were accepted after their meaning had been made clear. But a few were debated hotly.

The first of these was Number 9, the one about stealing. In drafting this, Allen and I had been deliberately vague. The proposed rule did not forbid stealing, but instead emphasized its consequences, both for medieval people and for our own group.

'So does this mean you can steal or not?' said Chris, who had returned that morning from his three-week family holiday. 'It doesn't actually say here that you can't steal, so I guess it means that you're allowed.'

'Well,' said Nina. I don't think you should be allowed to steal. It would wreck our village if everyone was going round stealing. I think we should make a rule that there's no stealing allowed.'

'But that wouldn't be medieval,’ said Chris. ‘We want our village to be realistic, and there was stealing then, lots of it. I was reading about their punishments in a book the other day, and in some places they would cut off a thief's hand.'

‘So we cut off people's hands if we catch them stealing,' said Nina dryly. 'That sounds like a great way to solve the problem!'

‘Do you think that making a rule forbidding stealing is the best thing to do?' asked Allen. 'Or is it best to leave it up to kids, knowing that stealing might cause unhappiness and might spoil the village.'

‘You have to have a rule if you want it stopped,' said one of the younger kids. 'Otherwise no-one takes any notice.'

‘I reckon sometimes having a rule actually makes kids want to break it,' said Paul. 'Sometimes it's good fun trying to break a rule to see what you can get away with.'

‘What happens,' Allen said, 'if we make a rule forbidding stealing, and then something goes missing? What happens if the rule gets broken?'

There was a silence in the room.

‘Well,' I said, ‘I think that if we make a rule and it gets broken, then we have to stop the village until we sort that out.’

'So, if we make a rule against stealing,' said Allen, 'we have to face the consequences if it gets broken.'

The discussion continued for another twenty minutes or so. As always when they were talking about something that really mattered to them, the kids spoke articulately and intelligently, and they listened carefully to what others were saying. They knew that there would be a decision at the end of the discussion, and that their vote counted.

When we'd started the discussion, the weight of opinion seemed to be that stealing should be allowed. But, as more kids talked about the consequences, opinion shifted, and in the end Rule 9 was amended to read:

9. Stealing is not allowed in our village.

The other proposed rule which caused us some difficulties was Rule 14, which said that kids who tried to gain financially in the village by selling, for village money, food made from ingredients taken from the food cupboard at home, or goods they'd bought with real money at Canberra shops, should pay an equivalent amount of village money to Effie. The rule was bitterly opposed by some kids, who felt it was most unfair that you had to pay twice for the one thing. Allen, Effie and I spoke strongly in favour of the rule, and in the end it was adopted by quite a large majority. But some kids were clearly unhappy with the outcome.

The discussions on the rules had taken the best part of four hours, with several longish breaks during which the kids played outside. As we broke up from our meeting with the last rule dealt with, Anna looked over at me and said loudly, 'Well, thank goodness that's over! That was awful!'

She looked tired, and I went and sat next to her on the step.

"Was it a waste of time, do you think?' I asked.

She thought for a second, 'I think it was worth it,' she said. 'We had to do it I guess, it's something you can't pass. But I didn't like it.'

She went off to the Abbott's house, while I sat for a moment and thought about her reply. She was right, I thought, and Allen had been right to insist on the whole group's involvement. As we talked about these rules and shared our ideas on what kind of a village we wanted to have, we were beginning to create our own reality, something much more than just the physical reality of the buildings around us.

Damien and Chris had come to see me earlier in the day, during a break in our discussions.

'Have you heard,' said Chris, 'that some of the kids are organizing a peasants' revolt to get Caitilin kicked out as steward?'

'Oh come on,' I said. 'We haven't started the village yet! What could Caitlin have possibly done that makes the kids want to get her kicked out?’

'I don't know,' said Chris. ‘Maybe they just like the idea of having a revolt. Anyway Paul's involved in it, and Tom, and some of the kids from the ale house.'

‘But I thought Caitilin had given Paul a job in the manor house as the steward's servant?'

In fact Paul had told me about it the day before. I'd looked through a window of the ground floor of the manor house, and seen Paul reading a comic. The nobles were upstairs organizing their private bedrooms. ‘I've got a job as the servant,' he'd told me, and, at that moment a bell rang and he disappeared up a ladder to the private quarters upstairs. 'Yes, sire,' I'd heard him say with exaggerated deference.

'Anyway, said Chris, 'we're going to double-cross Paul, and tell Caitilin what's going on.'

‘Enjoy yourself,' I said.

Chris smiled. 'We will Steve, don't you worry?'

Chris told me later that he was now the steward's servant, since Paul had been sacked for his disloyalty. But, when I talked to Paul about it afterwards, he had a different version of what had happened.

'Oh, Chris came in and asked for a job,' he told me, 'and they gave him a higher job than me. They made him the boss of the servants, so I resigned then. I handed in my resignation.'

I didn't know who's version was accurate. Perhaps, like us all, both were reconstructing history to fit their own particular view of the world, Chris convinced that he had outsmarted one of the more powerful kids in the class, and Paul that he had resigned with dignity.

After the rule discussions had ended that Friday afternoon the kids went off to their houses to put on their costumes, as we were going to have a brief meeting at the very end of the day for Lord Edmund to distribute the money.

As I went into the monastery to get my monk's habit, I saw David entering the gypsy house. There was something furtive about the way he glanced nervously over his shoulder before disappearing into the blackness of the gypsy house.

'David,' I called.

He came out, holding his hands awkwardly around a bulge in his shirt.

‘What have you got there?' I asked.

It was a bag of flour from his school bag which he was smuggling into the house to avoid having to pay Effie village money.

‘We've just spent hours talking about the village rules, and you're breaking them already, I said angrily, and I raised the matter at our meeting in the village square.

‘I've just found David smuggling flour into his house so that he doesn't have to pay village money for it. We didn't make those rules for nothing. It's not just a matter of following the rules that suit you, and ignoring the ones that don't.'

I could see that David was upset, and I wasn't sure that I'd done the right thing in castigating him publicly. But there was nothing I could do now until the meeting was over.

'Right,' said Allen, who was wearing his rich crimson robe. ‘When I sit in that chair over there, I'll be acting as Lord Edmund of the medieval village of Middleton, and you will then be my subjects.'

'Except for us,' said Anna. "You're not our boss."

Allen smiled. Perhaps the Abbott was going to be a formidable opponent. He walked over and sat in a chair just outside the baker's house. On a table in front of him there were about a dozen small cloth bags, each with a ribbon tied around the top. Some of the nobles were sitting on the balcony, their feet dangling over the edge, while the rest of the village sat on the carpet in the village square, and waited.

'Well, villagers,' said Allen. 'I look around me at the village that you have helped to build, and I can see that you've done an excellent job. I have here some money as a reward. You will no doubt notice that the shares are not equal. Those of noble birth will receive much more than those of humble parentage. The monastery will receive a large sum, which I will entrust into the Abbott's safe keeping. Abbot Gilbert, will you come now and receive your money?'

Anna stood up and walked over to the table.

'Thank you, Lord Edmund,' she said, as Allen passed her one of the bigger bags.

She was followed by the reeve, the baker, the two shepherds, Morgan the ale house owner, Martin the carpenter, and the blacksmith. The Lord asked each to bow before he gave them their portion, which some did gracefully and others curtly. Then it was the gypsy's turn.

'Paulo, would you come out and receive your money.'

Paul stood up, a determined look on his face. He hadn't liked some of the rules the group had passed, nor what I'd just said about his friend David, and it looked as though he was still carrying some of his misgivings.

"Well done, Paulo,' said Allen, and waited for him to bow. Paul stood upright.

‘Bow, gypsy, and then receive your reward.'

'I'm not bowing to any lord,' said Paul, and he looked around at his gypsy mates. There was nervous laughter from some of the younger kids.

'Bow, Paulo, or go back to your place empty handed.'

A flicker of hesitation passed over Paul's face, and then he turned round and sat down with the gypsies.

'Go on Paul, take the money,' said Kate, his village brother. 'That's our money there.'

‘I'm not bowing to him,' said Paul. All the humour had left his face. 'Stuff him.' Kate walked to the table and bowed, and Allen gave her the money.

As we left the meeting, I heard Paul say to the other gypsies,

'This village is going to be really dumb. Those rules suck?'

The others looked at him uncertainly, concerned about his feelings but not convinced.

After school, I found David, and we sat under a tree where he explained that, yes, he had felt upset that I criticized him publicly, but he also felt bad about what he had done. I told him that it wasn't the crime of the century, and that I'd probably over-reacted. We both felt better for the talk.

Then I looked for Paul. He was sitting on a log near the car park.

‘You didn't seem so happy at the end of the day,’ I said.

'It's just that I reckon some of those rules are a bit dumb,' he said. 'And I don't think there's going to be anything good to do in the village.'

"What sort of things would you like to be able to do?' I asked.

'Oh, I don't know. A war or something. Some kind of excitement. Not just buying and selling and that kind of stuff.'

I talked about the difference between plays and villages, and how you could let anything happen in a play - battles, people getting killed - but that there had to be more limitations in a village.

'Will you think about these things during the weekend?' I asked. ‘Maybe talk them over with your parents. Think about whether you'd like us to shorten the life of the village, and have a big play later next term instead. That's still a possibility. Maybe write down some rules or events you'd like to see included.'

'Yeah sure,' he said, in a tone that left me unsure whether he would think about the issues or just wanted to terminate our discussion. Then he went off to get the bus.