Part 2 Chapter 3: The pace quickens

From my book 'School Portrait' (McPhee Gribble/Penguin, 1987)

Like most of the children, I was becoming caught up in the excitement of creating our own imaginary world. But I was beginning to feel some pressures, too. We had fixed the weekend of April 14-15 for our brick-making workshop with parents, now less than a fortnight away. In the meantime, we had to plan the physical layout of the village, calculate the number of bricks needed, collect enough scrap cardboard from around Canberra, and draw the outlines of the bricks on the cardboard ready for the parents to cut and assemble. It was already clear that we would need something well over two thousand bricks. Had we bitten off more than we could chew, and raised expectations in the kids that couldn't be fulfilled?

I felt these things keenly as I worked with the children. The emotional legacy of the parent letter was still very much with me, and I felt a great deal of self-imposed pressure to make it all work, particularly as I was the only one in the room who had taken part in one of these villages before. I wanted the project to demonstrate how much was possible, how much was released in children when we tapped the deeper wells of their imagination.

During this fortnight, my main task was to supervise the finalization of the village layout, and, as a first step, we set aside about an hour one morning to make a scale map of the village site. The kids worked in pairs to measure and draw a scale outline of one section of our combined classroom. Then we put these sections together to give us a workable scaled map, which looked something like this:

We had decided to make the cardboard bricks ten times the size of a child's lego brick. This meant the kids could make a lego model or scaled floorplan of their proposed dwelling, and we could juggle these around on our scale map of the room until we had a village layout with which we were happy. On Wednesday afternoon of that week, I met with representatives from each of the village families or groups, to talk about where we would put each building. Anna, Jenna and Jessie were there from the monastery, Paul and Kate from the gypsies, together with about ten other kids. We crowded round the floorplan on the wet area floor.

'OK, I said, 'now how many of you have finished making your model or doing your floorplan?'

"We haven't done ours,' said Anna. 'It's too hard. Everytime we monks get together, we end up with a rough plan that's as big as our two classrooms put together.'

'And we haven't done ours yet,' said Catriona from the reeve's family. 'We can't agree, because some of us want two separate rooms, a bedroom and a sittingroom, but I don't think there's space for all of that.'

"Well,’ I said, 'we can't make any final decisions till all the models or floorplans are here, so finish them as soon as you can. In the meantime, let's put the completed ones onto the scale map, and see what space we're left with.'

The kids jostled and jockeyed for the best positions.

'Hey, we got there first!' shouted Paul. 'That's the gypsy spot.'

'No-one said it was first come first served,' said Jessie. That's where we want the monastery.'

'But you haven't even got a model or plan.'

'It doesn't matter. That's where we want it. We can have this spot, can't we, Steve?'

I wanted it all to go smoothly, for there to be thoughtful discussion and compromise, and so I tried to speak slowly and calmly. 'If two groups want the same space, then both of you put your model or plan... or just a scrap of paper... there. We'll sort that problem out later. For the moment we're just trying to see if everything will fit, or whether we're all going to have to reduce the sizes of our buildings.'

"We're not making ours any smaller,' said Caitilin from the manor house group. 'We've got seven in our group, and we can barely fit as it is.

'Can we leave that til later?' I asked. 'Let's just have a look at what we've got now.'

The kids adjusted their models, but it was obvious straight away that we wouldn't have enough room.

'Has anyone got any ideas how we can make more space?' I asked.

"Well, for a start I think the monastery should be smaller,' said Caitilin. Anna, her best friend, glared at her.

'But don't forget,' I said, that monasteries were communities, and they had different spaces for different activities. If we want our monastery to be realistic, then it will have to have a fair bit of space.'

'You're only saying that because you're a monk,' said Caitilin. 'We want to have our proper space too.'

"I wouldn't mind building my cottage in the spare room,' said Damien. 'That would give us more room.'

‘Well, I guess that's a possibility,' I said. ‘I would rather we were all in together though.'

'We could build outside,' said Mark, one of the blacksmiths. ‘Our forge is outside, and I think it would be better if our cottage was just next to the forge.'

That sounded feasible, so we moved the blacksmith plan to the outside, and Damien's tentatively to the spare room, but it was obvious that we still needed more space. It was the end of what had been a busy day, and the kids were beginning to look tired and drawn, so we left it at that. As they left, I reminded them that we needed all scale models or floorplans finished in time for our next session.

That night, I couldn't sleep. I kept seeing floorplans whenever I closed my eyes. I got up at about 3 a.m. and drew up a suggested layout, based on what the kids had said during the afternoon, but with a space for Damien's cottage inside our classroom.

I showed the plan at our class meeting the following morning, but some of the manor house people were still not happy with it.

'It's going to be like a poor house in there,' said Nina, who was going to be one of the lord's cousins, 'with everything so crowded. We're meant to be rich and grand. It just wouldn't be realistic. It wouldn't be any fun being a noble if we had to live all squashed together.'

'But if we make it any bigger,' I said, ‘then there'll be no room for the reeve's house. Where could we put that?'

I think what they're saying about the manor house is right,' said Allen. 'It does need to be bigger. How about we build the manor house with two stories? I've got enough timber at the moment for us to build a solid timber frame.'

'Yeah,' said several of the manor house people. 'Great. That would be really good.'

"It would look good, too, said Allen. We nobles would be able to look down over the rest of the village from an upstairs balcony, which is only right and proper given our importance.'

It seemed like the perfect solution. I discussed it with the manor house and reeve's families after the meeting, and they quickly agreed to a plan which left plenty of room for the reeve's house.

I was now feeling that a major hurdle had been jumped, that all our planning problems were over.

I was wrong.

I met that afternoon with the representatives from the different village families. I showed them how we would overlap bricks in our walls for strength, and how this meant that we needed some half-bricks at the ends of walls and next to doors and windows.

Then they went off, to calculate how many bricks they would need.

Within about ten minutes, things began to fall apart. Cameron came in tears, saying he was feeling sick and didn't want to do this. He went off to rest. Mike seemed unable to work with Anicca and Katherine, and was feeling excluded. Shaun couldn't see how the ale house was going to fit, and I could hear the beginnings of a quarrel in the top room between the monks and the gypsies.

At the edges of my unconscious mind, I was only too well aware of what the basic problem was. The plan that I had drawn up the night before, and which we had agreed upon that morning, was unworkable. The various buildings might fit neatly onto the scale map, but, when the kids came to measure them out in the room, they were obviously going to be much too cramped.

But it was a truth that I didn't allow myself to face at the time.

Its apparent consequence, so my tired mind told me - to start the planning all over again - was too unpalatable, and so I unconsciously looked around for a scapegoat. It was then that I discovered that Damien, who had built his model at home the night before, had planned a cottage that was much too big for his allotted space.

'Bloody hell, Damien!' I shouted, completely forgetting that he had gone home the previous night under the understandable impression that he could build his house in the spare room, and that it could therefore be as big as he liked. ‘We've been working for days on these designs, and we've finally come up with a plan that fits, and you've gone and designed a building that's far too big! Now the rest of us are going to have to wait around while you redesign your house. I wish you'd think, and do things properly!'

Damien would have been justified in shouting back at me, perhaps as petulantly as I had done. But my outburst had been so emotional that he was probably confused into thinking he'd done the wrong thing, and so he walked away gloomily to redesign his cottage.

Then I heard shouting coming from the wet area in the top room, where Anna, Jessie and Jenna were arguing with Paul and Kate about the relative positions of the monastery and the gypsy cottage.

'You can't make your cottage that big!' shouted Anna, her face red. If you have your place that big, then there'll be no way to get into the monastery. You'll block our entrance!'

‘How are we going to fit four people into this gypsy house unless we make it that size, tell us that,' said Paul, calmer than Anna but very involved in the dispute. 'That's how big it needs to be, and that's how big we're going to make it.'

'So how do we get into the monastery? Crawl over the roof, or dig a tunnel? God, you think you're the only ones in the world, don't you!'

"Very funny. Build your entrance somewhere else. That's your problem …’

I wanted to get over there to help, but kept getting waylaid. Katherine, a shepherd, and Shaun, an ale house planner, wanted help counting their bricks. Catriona was struggling with a floorplan for the reeve's, and Damien came to see me with a new plan. Once again I took my frustrations out on him.

‘If it hadn't been for you not listening, things wouldn't be so chaotic now. I just don't think you realize how hard it is trying to coordinate all of this planning. I'm feeling tired and pressured,' I seethed. "You too, Catriona. I can't understand why you haven't got your floorplan done when I made it clear that they had to be ready by this afternoon!'

This was too much for Catriona, an extremely eloquent and sensitive person with a a very strong sense of fair play. 'I'm sick of listening to you going on and on like this, Steve!' The words came tumbling out, her voice shaking with emotion. 'For the past couple of days you've been so critical, so unhelpful. You're not the only one feeling tired and pressured. You're being horrid and unfair and unreasonable. We're trying our hardest, and you're criticizing us all the time! You're not being like a proper teacher?’

I was taken aback. She'd never spoken like this to me before. She was crying now, half angrily I thought, and perhaps a little frightened by her own vehemence.

‘I'm sorry if I'm being unreasonable,' I said, trying unsuccessfully to sound contrite and conciliatory. ‘But I really don't think I'm the only one at fault here. We're all finding things hard. We've got to find a way round these problems, or else we'll never get the village designed.'

The kids returned to the planning, but their energy was spent and the session drifted to an unhappy and inconclusive end. After school, I told Allen what had happened.

‘Why don't you take the day off tomorrow, and just let things settle?' he said. ‘We can manage, and it won't matter if the plan isn't finished for another day or so.'

I was too exhausted to think that night, but I spent the following morning alone at home, and realized how unfair I had been to Damien, and how I was getting things out of proportion. I'd been letting the responsibility get to me too personally and, despite the good work I felt I'd done in helping the idea get off the ground, there was a danger that, unless I found a less emotionally-charged way of guiding the project, it would flounder unhappily.

I returned to school at lunchtime in a more relaxed frame of mind. I apologized to Damien and Catriona, and explained how Catriona's outburst had helped me see how badly I'd handled the situation.

At our next planners' meeting, passions seemed to have cooled, and new solutions presented themselves. The ale house group moved their floorplan into a quiet room, and Damien suggested he build outside near the forge. This gave us much more room, and we decided to have a decent sized village square where we could meet, and where markets could be held. Our final plan was as follows.

I talked to Allen after the meeting, and together we decided that I would take a back seat for a while. So I spent some time watching Allen and a group of about ten children making the clay coins for the village. There was a difference of opinion between those who wanted the designs to be complex, authentic, and aesthetically pleasing, and those who wanted something more simple and practical. In the end it was the simpler designs that were adopted, mainly because the time for building the village was fast approaching. The kids stamped mirror-image plaster copies of their designs onto rolled-out clay, and used simple metal cutters made from scraps of sheet copper to cut out the coins. Once the coins were finished, they were loaded onto trays and taken up to the secondary art room to be fired.

I spent time, too, just looking around the room at all the different activities. Some kids were still engaged in their research, leafing through books, using individual viewers to watch filmstrips of medieval clothes and customs, and listening through headphones to a tape about the Black Death. Others sat around in family groups, talking about the costumes they were making at home, drawing family trees, or making final adjustments to their lego model. And every now and then Effie and some kids would come back in her van, and we would rush outside to help unload another forty or fifty sheets of cardboard scavenged from various waste disposal bins around Canberra.

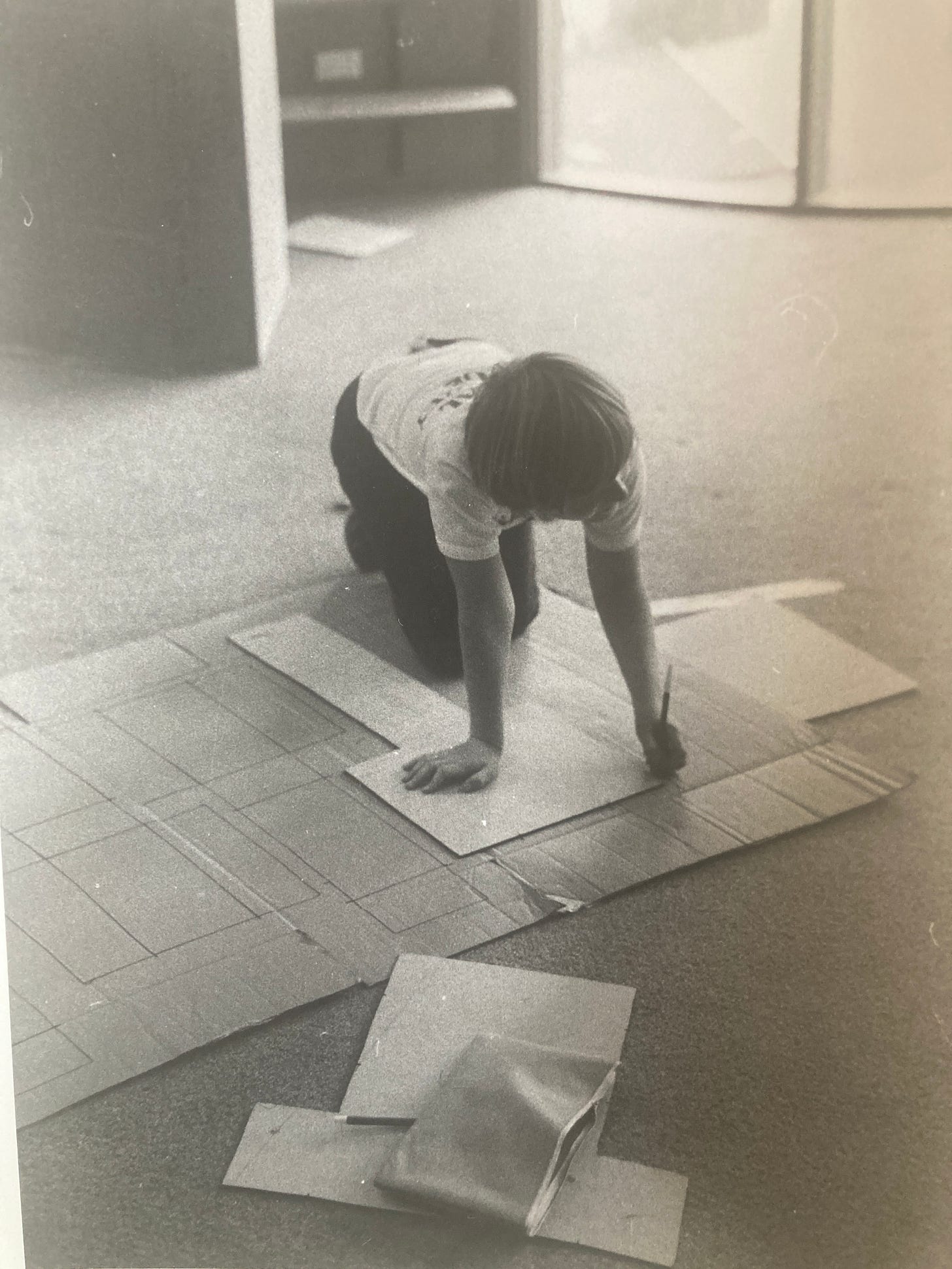

Effie showed the kids how to make cheese, Allen helped the carpenters and blacksmiths acquire new skills, and I brought in some medieval music to play with a small recorder group. We experimented with watering down the glue, to find a mixture that was both economical and strong enough to stick the cardboard bricks together. We moved all of the classroom furniture into the spare room. And whenever anyone - child, teacher or visitor - had a spare moment, we had to take our templates for the bricks and draw seemingly endless numbers of outlines on the sheets of cardboard.

***

I also looked in at two groups working with Bernie, the school's Principal. I've always enjoyed watching Bernie work with kids. He's a big man, an amateur basketballer, with a heavy black beard and large hands. When I first met him, I found his physical presence quite intimidating, but children are quickly at ease with him. He has a quiet, laid-back manner, and kids sense that he respects their opinions and their work, that he's around to offer advice or make suggestions if asked, and to help open up new possibilities in their thinking with his gentle questions.

One group was making the village copper pounds. The kids worked on their designs, and discussed these with Allen and Bernie. Once they'd finalized a design, the children cut the coins out of a sheet of copper, dipped the round coins into wax, carved the designs through the wax onto the copper underneath, and then dropped the lot into an acid bath until the design had been burnt into the copper.

For Bernie, as he told me afterwards, it wasn't the final products that were important; the coins were uneven in quality, which was not unexpected given that it was the kids' first effort. What impressed him was what the children discovered along the way. They discovered that it required a certain amount of strength and patience to cut the copper, that it wasn't like paper; that wax cracked when it cooled, and so had to be etched quickly; that it was impossible to etch if the wax was spread too thickly, and that it came off in great slabs if you tried to scrape some of the thickness off; that they needed to design little wire cradles so that the wire edges touched the coins in as few places as possible; that working with copper and wax was like working in a sandpit, in that you could smooth out mistakes and quickly re-dip your coin; that acid is both alluring and dangerous, to be handled with extreme care: that an almost invisible sliver of wax remaining in an etching would be enough to spoil it when it was dipped in the acid. Ra found that if he took a sharpened hardwood stick, and tackled the coin quickly as it came out of the wax, while there was still some warmth in it, then he could etch it really well, and cut the wax off in broad lines, the broader the line the better the image. Bernie told me that most of the kids in that group could now be trusted to do the whole process, including the acid bath, given good surroundings and limited supervision.

He also talked to me, in a recorded conversation we held some months later, about the other group he was working with, who were making six stained glass' windows for our monastery church. The windows were begun before the village was built, but continued during the first week of the village's life, with Bernie, in the role of mastercraftsman, coming down to supervise the work three or four times a week.

He told me how he showed the kids some examples of stained-glass windows in books. He'd been to Europe in 1982, and had visited the cathedral in Chartres. 'Of course,' he told me, 'standing in a twelfth-century cathedral, bathed in twelfth-century light, if you like, is different from looking at stained-glass panels in a book.' But he also brought in bits of lead-lighting and described to the kids the sorts of processes that people would have to go through to make it.

He told the kids how medieval stained-glass windows were there to influence people, to get them to take the right path, the righteous path. He told John, one of his craftsmen, that his (John's) centrepiece was the big message - God, with his finger in the air pointing to the Way. Because very few medieval villagers could read, the Church was teaching them through the images on the windows.

‘We even talked a little bit about the cathedrals themselves, how they were built. I had some huge posters of the flying buttresses, and I'd seen a guy demonstrate by getting half a dozen people together and asking them to put one hand up and link it to the hands of the others, with everyone standing in a circle. Then a fifteen stone guy stood in the middle of the circle, puts his arms around the knot of hands, and hung there …’

The stained-glass windows that the kids produced were made paper. coloured cellophane, and the leading of black strips of paper. Because he was the mastercraftsman, Bernie told the kids what the steps in the process were going to be. In that sense, there was less experimenting than with the copper coins. He pinned up these steps in what was to become the village church, and the group worked alongside the window where their stained-glass designs were going to be put. It at any stage a kid wasn't sure what to do next, he or she could just look at the charts up on the wall.

They started with drawings that were done to agreed themes, themes that they'd checked with the Abbot [Anna] - 'he had to give us the nod'. There were six panels on this window, and each kid was given one of the panels.

Bernie talked about his craftsmen. David and Shaun chose to make a very intricate rose window, and their small hands were having a lot of trouble making the many tiny circles. Their elaborate idea outstripped their ability to carry it out, and, after a while, they started to get discouraged. Bernie lent them some metal punches, ones you hit with a hammer instead of squeezing a trigger, and they found that easier. 'At that point it's more than just being involved in the process of making a stained-glass window,' said Bernie. 'It becomes important for kids like these two to get something completed, to feel good about it. If you're feeling good about the task, then you're feeling good about yourself, you get some kudos from your friends, and the next thing you'll do you'll most likely tackle in a different way.'

There was Catriona, who was wanting to do beautiful things and do them on time and do them well. She was very task-oriented; and Clare, working on the floor, always busy. She would come to the mastercraftsman to get instruction and guidance, very careful and serious about her work.

'Then there was Dan, who glowed all through it! He cruised! He was so serene about that work, and it was easy for me to say to myself, "Oh, Dan's going well, he's right," and to forget about him. He was just serene. He was happy with his design, and he said very early on, "Hey, I'm going to take this home and put it in my room when this village is over." It seemed to me that the activity suited him right down to the ground. He'd never come across the idea before, and for him it was one of those amalgams.' As Bernie talked about Dan, I thought again about Dan's reading of the story to his father. Some would see this stained-glass window work as some kind of brief but welcome respite for Dan from the battle he was continuing to wage with reading and writing. To me, these experiences seemed somehow to be actually helping him with these basic skills.

Bernie decided that one of his craftsmen would make a lead-light cross for the Abbott. He brought some bits of coloured glass and discussed with the group the different qualities of the glass and how to cut it. John got interested in this. He was fascinated with technical things, like how to cut glass. 'As soon as I produced a glass cutter, he eyed it, got hold of it, tried the wheel, spinning it to see how it worked, and looked at it from different angles. He was fascinated with that stuff.'

They decided, though, that just one person would tackle the making of the lead-light cross. Tom was chosen, and his finished cross had a centre which was blood red, symbolizing the heart of Christ. 'We read a few scriptures about that, the symbolic nature of the cross. The Holy Spirit was surrounding the cross, done in orange glass round the outside. Some of these symbolic ideas were new to the kids, and when I was talking about them, it was very quiet. The kids were all really listening.'

When they were doing the drawings for the windows, John was distracted. He found the task-direction awfully difficult to cope with, and the others got angry with him slipping out of role when he felt like it. On a couple of occasions the mastercraftsman got angry with him, and made some loud noises about payments. 'We were already talking about bartering with the Abbott about prices, and we listed our names on the wall, to help us work out who would get what proportion of the lump sum. I talked to the kids about percentage, and then gave myself a whacking slice of the cake, because of course I was providing the skills. I got some pretty strange stares from Catriona, Clare, Dan and Shaun, but I told them, "If I wasn't here, then you wouldn't get anything, would you," and that seemed to be generally accepted.'

John's slice was not big. In fact the group decided that John's slice should be minimal, and he was pretty upset. But he finished that stained-glass window with Bernie helping him paste up the cellophane. 'You're caught. What do you do? Do you let the kid not finish it, and have the consecration of the windows with this glaring non-event? John had chosen this figure of God pointing to the cross above. The kids were pretty impressed with his drawing, but he didn't carry it through. I said to myself, I can't cope with John getting heaped by the group. And yet if I'd really been a believer in natural consequences, then I'd have said to John, "Your life will unfold. That's your consequence." He would have been unmoved by the experience, or worse. Now, although I gave him lots of help, if you asked John, "Who made that stained glass window?" he would say, "Me, and isn't it great!"

'The personalities of the kids were so obvious as they worked on the stained-glass windows. It's true, isn't it, that if you provide any activity for kids, it's their personalities that will tackle it. Their personality will be stamped all over it, the way they go about it. Look at Anna's doll house [described in Chapter Six]. That's got Anna all over it. She couldn't have done it without a lot of help. The copper coins couldn't have been done without a lot of help. The stained-glass windows couldn't have been done without a lot of help. But, if you ask the kids, they still own that project. It's their project. I think this is the trick of teaching - you've got to allow the kids to own the things, but to be able to intervene strongly enough, to display your skills and give them things that they can manage.

‘With all these activities - and it's the same with the maths they do, when they sit down and read a book, when they're drawing - they're just trying to make sense of what the hell is going on in the world. At these middle and upper-primary ages, their social horizons have expanded already and their intellectual horizons are now starting to expand at a really rapid rate. They want to know 'why' more, and they don't just want superficial answers. So, when you talk to them about acid, when you talk to them about the properties of glass, if you explain these things in an imaginative way, then they really respond.

'And this is linked with us feeling confident ourselves. I couldn't have done the copper coins if I hadn't used acid before, I wouldn't have talked to them about stained glass unless I'd worked with stained glass before. It helped, too, that I had stood in these twelfth-century cathedrals and felt moved, that this was revered space, it's quiet and it's warm and it's bathed in this incredible light?

After we'd built the village and installed the stained-glass windows, I walked into the church at a time when the sun was pouring in. Like the twelfth-century cathedrals that Bernie talked about, our church was 'quiet and warm and bathed in this incredible light'. I felt excited by what the kids had achieved, and moved by the very tangible imaginative links we had made with the craftsmen and people of the Middle Ages.