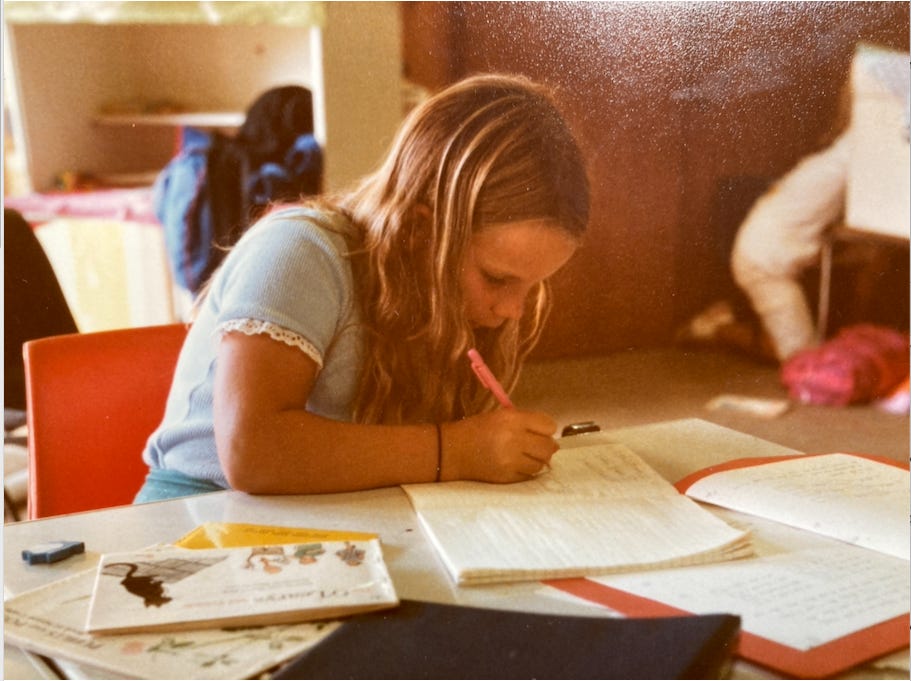

Part 2 Chapter 2: Getting into the mood

From my book 'School Portrait' (McPhee Gribble/Penguin, 1987)

We began our research in earnest during the following week. The kids sat around tables in their family groups, and poured over the many books they and their friends had borrowed from the school and public libraries. Andrew, who wanted to be a knight, had an article about late medieval weaponry, describing the various pikes, lances, swords, daggers and the chilling spiked ball. There was a picture of the crossbow, made from native yew and goose-feathered 'by craftsmen of hereditary skill', and of the cumbersome and unreliable muskets and cannons which were 'as likely to cause casualties amongst friends as foes'. Peter, a worker in our village's ale house, brought a book of medieval recipes, and told us of the contrast between the peasants' simple fare - ale, rye bread, cheese and dinner of tough old ewe mutton - and the feasting of the nobility. One lord, he told us, had entertained a visiting cousin with a three course banquet which included boiled mutton with spiced sauce, brawn, pike, capons 'of great fatness', pheasant, baked custard in pastry, venison, suckling pig, eel pie, chicken in saffron with egg yolks, fruit pie, white curd and meat cooked in almonds, quince pie, eggs in jelly, marzipan sweetmeats and jugs of wine and ale.

I told the kids about an article I'd seen recently in The Canberra Times. Some archeologists in Oxford had uncovered a medieval pit toilet used by the warden of one of the colleges. Scientists had examined the dried fecal matter, and had discovered that the warden's family or guests had eaten all sorts of extravagant and rich food, such as figs imported from Turkey.

Siobhan brought in The Story of an English Village, a book of some twenty pictures with no text, showing the growth of a village from a clearing in a medieval forest to a busy twentieth-century traffic intersection, seen from the same viewpoint every hundred years or so. In the last picture, the church, market cross and ruined castle are still visible amongst the cars and modern buildings. Damien had books on medieval castles - he'd discovered that a branch of his family owned Berkeley Castle, where a medieval king had been cruelly put to death - and there were gruesome stories told at his table about the medieval dungeons, including the ghastly practice of locking someone in a secret dungeon called an oubliette where the prisoner would starve to death, his body the prey of worms and rats until only the skeleton remained. Kate, the gypsy doctor, read about the four humours; melancholy, choler, phlegm and blood; Jessie, who wanted to work in the monastery's infirmary, made a list of traditional cures, including this one for toothache:

take a candle of mutton fat mingled with the seed of sea holly; burn the candle as close to the tooth as possible, holding a basin of cold water underneath. Worms gnawing the tooth will fall into the water to escape the heat of the candle.

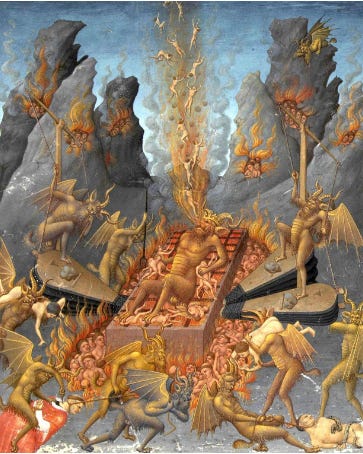

In all these books there were photos, drawings, and reproductions of paintings which the children wanted to talk about. There was a painting of a monk in bed with a nun which caused much merriment, a wood carving from Carlisle Cathedral showing a wife beating her husband, and the many paintings of Brueghel of village games, dances and a wedding feast. The children were both horrified and fascinated by the scene from the Duc de Berri's Book of Hours, depicting the tortures of hell, with the damned souls being held over a fiery pit in the claws of a giant Satan, while elsewhere others are being stabbed, dragged by ropes and hurled into the flames by monstrous horned devils.

The children wanted to know why so many medieval scenes were haunted with the image of death - the skeleton head of Death on tombstones, in paintings, even in stained glass. We talked about the shorter life span, the wars, poor sanitation and diseases, and we found many references to the Black Death, including the anonymous inscription made on the half-finished wall of Ashwell Church where work ceased because of scarcity of labour. It reads in part:

1350: wretched, wild and driven to violence, the people remaining become witness at last of a tempest. On St Maur's day this year 1361 it thunders on the earth.

Less dramatic, but no less interesting for some, were the floorplans of castles, monasteries, and manor houses, and the photo of a still-standing medieval cottage in Berkshire, built around triangular timber supports, with lath-and-plaster walls and thick straw thatch roof.

At the same time as this book-based research was going on, a parent organized a trip to the National Library where the children were allowed to touch original medieval documents, a student from the School of Music talked to us about medieval music and instruments, Margaret (the teacher of the five-year-olds at the AME) showed us slides of an illuminated Book of Hours, and we had a visit from a member of the Society for the Promotion of Creative Anachronisms. John was a part-time blacksmith, and he came with his portable forge. He told the kids stories and answered their questions as he lit his fire, heated and beat the red-hot iron, and, amidst clouds of steam, tempered the hissing rod in a bucket of cold water.

It was an important session for our blacksmiths. They had already searched various libraries for material on forges, but everything had been either too technical or too general. John provided them with all the information they needed, and they spent the succeeding days scouring the school for suitable materials for their own forge. They found a 44-gallon drum, and Mark and his dad cut it to the required shape. They found pipes, and a crank handle, and, one Sunday afternoon, Eli's dad and Allen spent a couple of hours with the blacksmiths, assembling the forge. They put two holes in the drum, positioned the pipes, and attached the crank handle in such a way that, by cranking vigorously, air would be forced into the drum, so that it acted as a kind of bellows. Then they packed the drum with clay and bricks to make the fire chamber, lit a fire, and their forge was functioning.

The more we did, the more the group became fascinated with the medieval age. One particular Friday afternoon, I began to read from a book called Living in a Medieval Village. It's subject was the village of Benfield and its residents, Sir Richard Dauncey the steward, his wife and their servants, Ralph Pigge the reeve, Gilbert the smith and various other tradesmen, villeins, freemen, cottars and widows. It described the seasonal work each did, the buildings they lived in, their customs, leisure activities, festivals, and a session of the village's Manor Court. Several times I tried to stop reading, and each time I was urged to read more, until, an hour and a half later, I finally finished it.

Parents were beginning to send us notes, like the following:

Andrew's obvious enthusiasm for the project and growing knowledge about things medieval have been a delight to see. We are all getting a lot out of his research, which involves us both and even our friends. Andrew has been wanting to plan and write most nights and really looks forward to trips to the library and every new development at school.

Jessie is very excited about everything. She rather hankers after looking elegant, but is slowly realizing that as a peasant girl that's not possible. She has a little doll in a long dress, and various implements like a spinning wheel and a pump, and she spends every spare minute play-acting life in a medieval village. We have conversations about food and medical care in those times, and she is rather glad that she lives in the twentieth century. The fact that she spent a winter living in Europe helps her to understand the scarcity of fresh food and the need for warmth. She's also keen to learn about medieval script, so we'll be spending some time on that. All in all, it's practically all we do or talk about at the moment.

One Tuesday morning at the end of March, I sat at a table with the other monks as they looked through books and talked about life in a medieval monastery. Anna was writing the story of her character, whom she had decided to call Gilbert. The rest of us - Matthew, Dan, Mike, Jenna and Jessie - were listening as Kleete read to us about the daily life of monks.

At Canterbury the first service of the day was at 2.30 a.m., when the monks were woken and came down the night stair from the dorter into the Church for matins ... [There followed] Lauds at 4.30 and Prime at 6 a.m., with no hot coffee, tea or cocoa in between, it must be remembered, and for more than six months of the year this would all be before dawn. The monks then read or walked in the cloister until 8 a.m. Then they changed their shoes, washed, and went back to church. The Daily Chapter followed, then more church for Sext, High Mass, and None, then their luncheon at 2 p.m. after which the monks changed into their night shoes again, were allowed a drink in the frater, and then to church once more for Compline, the last service of the day. Lights were out at 6.30 or 7 p.m. in winter, and at nightfall in summer. Added to all this were the long periods of fasting.

'Hell, I don't want to be a monk any more,' said Mike. ‘Imagine being woken up every night for that. We're not going to do that in our village I hope!'

He was relieved when I explained that many monasteries were less strict and more worldly.

Anna looked up from her story. 'Steve, what's the name of some place in England?' she asked. I'm writing my life story and I want to say where I was born.'

The words of the old song came into my head:

Are you going to Scarborough Fair?

Parsley, sage, rosemary and thyme,

Remember me to one who lives there,

She once was a true love of mine.

'How about Scarborough?' I said. I sang the first verse of the song to her, and we talked for a while about medieval fairs.

Jessie was looking at a floorplan of a monastery. 'What sort of rooms are we going to have?' she asked. 'In this one there are dormitories, the church, the chapter house, the Abbott's house, infirmary, library, scriptorium, dining rooms, washrooms, gardens, pigsties, blacksmiths - goodness, it's got everything, just like a village! Are we going to have all of these things too?'

"We couldn't build all that,' said Matthew. 'There isn't enough room! Anyway, we'd never get finished.'

'It all depends on what you people want in it,' I said.

'An Abbott's house,' said Anna firmly. 'We have to have an Abbott's house. I want a bedroom, a dining room, sitting room …’

'Come off it!' said Mike. ‘Where do you think we're going to fit all of that?'

‘Listen,' Anna said. ‘I'm meant to be important. I read yesterday that lots of abbotts were really rich, and they used to do stuff like have the king to dinner. I can't live in a little hole. That wouldn't be proper.'

‘ I want to mix herbs and make medicines, and look after sick people,' said Jessie, 'so we'll need an infirmary.'

'And a scriptorium,' said Kleete. 'Dan and me were thinking of making illuminated manuscripts and stuff like that.'

'And we've got to have a church,' said Mike, 'and somewhere to sleep.'

'I'm going to be sleeping in the Abbott's house,' said Anna grandly.

'What about a dining room and kitchen?' I asked. 'Are we going to eat together everyday, like they did in the monastery?'

'Yeah,' said Dan. 'They weren't allowed to talk at the meal. except for the person reading from the God book, or whatever it was called.’

'The Bible,' said Jenna.

‘... yeah, the Bible. Anyway, no-one could talk, and they had to make signs to each other if they wanted something passed. You probably had to stick your finger up your nose if you wanted the salt!'

"You wouldn't have any troubles with that, would you, Steve,' said Chris, who had drifted over to our table and was listening in to the conversation.

Just at that moment, Paul and David burst in the door, laughing and pushing each other playfully. They'd been up at the library, trying to find out about gypsies.

'Just wait till you see what he's going to look like in this village!' said Paul, pointing to David.

‘I'm not wearing that, I can tell you,' said David, with a grin. ‘You should have seen it, Steve!'

"We were up in the library together,' said Paul, trying to find out what gypsies ate, what they wore and things. We're looking through this book, right, on clothes in olden times... Page 228, page 229, page 230 …’

Paul licked his finger, and turned imaginary pages as he talked.

‘... page 231 ... hang on, here it is! And there was this picture of a gypsy, wearing this funny sort of frilled dress, and Dave goes "Oh shit, I'm not going to wear that!" And the library was all quiet, and everyone could hear him, so we got chucked out.'

‘Well, I'm not wearing it, so don't think I will,' said David.

He pushed Paul again, and they went off laughing.

I went back and sat next to Anna for a while. She'd written a page or so of her story, and had paused for a rest. 'How's the work going?' I asked her.

"Oh, I like writing the story, that's fun,' she said. 'But the research is difficult. I don't understand the books, they're too hard for me to read on my own, or mostly anyway. I have to get you or Mum to read to me. But it's interesting, the stuff you find out. Like monasteries were much more strict than I thought they would be.'

Later that week, I went to the drama room with a group of about twenty children. Paul and Chris were both there, and all of the monks, including Anna and Dan. I took out a small bag of red, blue and yellow counters, and tipped them out onto the floor.

‘The red ones represent pounds, the blue ones shillings, and the yellow ones pennies,' I said. 'In a few moments, you will be acting the part of your village characters, and we'll run through a day in the life of the village. We'll use the counters as pretend money. How should I distribute it?'

"Share it equally, that's fair,' said one.

‘No, about two pounds for each nobleman, and one for each normal villager,' said someone else. ‘The nobles should get more than everyone else.'

'What about the Abbott,' said Anna. ‘I'm meant to be well-off. I should have two pounds too!'

"OK, I said. Now watch.'

I gave each peasant male three pennies, and nothing to the wives and children. Then I divided all the rest (the equivalent of some 50 English pounds) up into two halves, and gave one half to Caitilin who was representing the lord, and one half to Anna as abbott.

'Hey, that's unfair!' shouted most. 'You can't do that!' They were genuinely shocked.

"Well,' I said. 'Do you think I should divide up the money fairly, or according to how the wealth was distributed in medieval times?'

There was a silence.

'But it wasn't really like that, was it, Steve?'

'Essentially, that's exactly what it was like. The peasants were poor, and most of the nobles were very rich. So were some of the monasteries, and certain abbotts lived lives of luxury?'

Anna beamed.

'In fact,' I continued, 'not only were the peasants poor, but they had to work for the lord on particular days every year without getting paid for it. And they had to give the lord a proportion of what they produced. On top of all of that, most of them had to pay something like one-tenth of their produce to the Church.'

Some of the kids looked at me with mouths open.

'Why? How come? That's stupid!'

‘Well, it was the lord who owned the land, and he gave the peasant the right to work on the land in return for these goods and labour …’

'Bloody Allen,' said one of the kids.

‘... and the lord also offered protection to the peasants. He had a castle, or some kind of fortified house, and he had soldiers loyal to him. These were unsettled times, and often lords or barons attacked each other, so the peasants needed protection from warring nobles.' I wondered whether we should abandon our drama session now, and talk more about some of the issues here - how the lords were given the land in the first place, the Church's view of it, and the rebel catch-cry, ‘When Adam delved and Eve spun/Who was then the gentleman?' But I sensed that the kids were ready to move on.

The kids each took their share, muttering to each other about the distribution of wealth, and went to the corners of the room to 'set up house'. Then, at a given signal from me, everyone began what they felt might be a typical village day for them.

Paul and the other gypsies were quickly into fortune telling.

'Stare deeply into my eyes,' I heard Paul say to one 'villager'. 'Ah yes, I see that you will soon be giving money to a stranger. That will be one penny please. Thank you.'

Anna gathered the monastery's small fortune into a handkerchief, and walked round the village, spending her money freely, and dismissing beggars with a sweep of her arm. She came up to Tegan, the reeve's wife, who was her village sister.

'Hullo, my dear sister,' said Anna.

'Ah, hullo Gilbert. And how are you today?'

'Oh awful. All these villagers shouting and bothering me. It's just dreadful. And my money is so heavy, I can hardly be bothered with it.'

"You could give some to me if it's a trouble to you,' said Tegan.

'Of course, of course!' said Anna, and gave Tegan a handful of blue, red and yellow counters.

I hurried over to where the other monks were pretending to copy manuscripts and mix herbs.

‘Have you seen what our Abbott has done,’ I said in a scandalized voice. 'He's giving the monastery's money away to one of the villagers.'

The monks looked at me blankly.

'It's the Church's money.'

Still no response.

'Can't you see! We can get him into trouble for this!'

Eyes lit up, and work was put to one side.

'Let's call a monks' meeting,' called Mike. 'Abbott, there's a monks' meeting over here.'

‘I can't be bothered with that sort of thing,' said Anna from the other side of the room.

'We'll tell the Pope. You'll be kicked out as Abbott,' I said.

'Well, in that case..?' And Anna hurried over to where we were sitting.

I could see from the corner of my eye that other little cameos were taking place all around me. Taxes were being collected, arguments started, there was a fight between a couple of drunk villagers, and money was changing hands. I left all that to work itself out, and turned my attention back to the monks' meeting.

"Now what's all this rubbish about,' said Anna, still very much in role and looking contemptuously at us, her subordinates.

'We know that you've been giving Church money away to the reeve's wife,' I said.

'So what! I can do what I like here.'

'But that's not your money, Abbott Gilbert,' I said. 'That belongs to the Church, to this monastery. It was given to us to be used for God's purposes, to feed the poor and care for the sick, and to build wonderful cathedrals where people can worship God.'

Anna held her chin high, to give the impression that she was looking down on me. But she was less sure now, and I suddenly sensed that this was proving difficult for her to handle. I changed my tone.

‘We know that you do things for the best, Father Abbott. That's why we elected you. But we don't think you should give away money. You might get into trouble if the Pope heard about it.'

'All right, all right,' she said impatiently. 'Go back to your work, I've heard enough of all this.' Some of the bounce had gone from her voice. She was looking a little shaken.

After the drama session, I had a talk with Anna. She told me that she was having trouble getting the other monks to take her seriously.

'Dan is OK,' she said. 'But the others take no notice of me.'

‘Maybe the way you talk to them annoys them,' I suggested.

'But I'm meant to be posh and bossy,' she said. 'That's what my character's like.'

She was right. She had quite consciously set out to be dictatorial. It was the others who were finding the Abbott's personality a problem, not Anna herself, though she wasn't enjoying all the consequences. It was to become a major theme for her once the village itself began.

Anna spent a long time making a good copy of her story, with a special italic nib from a set that Allen had brought in. She wrote:

I was born in Scarborough. My father was a noble - well, not really a noble. He was really good friends with Sir Bartholomew Whorrall. I was brought up in a manor house and when I was fifteen I turned into a monk and I lived in a monastery for thirty years and then they decided that I would be their Abbott. At first I had a lot of difficulties. [Anna wrote this after the drama sessions.] I have been the Abbott for five years, so I have been living in the monastery for thirty-five years but it is worth it. Some of the monks that I am working with have been here for just as long as I have. I am fifty now, and growing old, and some day we might decide on another Abbott if I die. My mum and dad live in Jerusalem. They write when something happens. I have a pet bird what carries the letters from me to them. My mother works as a cook in Jerusalem and my father helps sometimes at the monastery and he sometimes helps with the gardens and things. They get paid a lot - ten shillings a day. My dad is ninety and my mum is eight-six and I have a sister named Victoria and I don't know how old she is. She is the reeve's wife and lives in this town. Sorry, no more time to write.

It is time for prayers.

Love, Gilbert.

I don't have any of Paul's writing from this time. Chris, though, spent a long time on a story (which was unfinished because he went off on the family holiday), and also on a letter to his imaginary mother, and in both he carefully decorated and enlarged the first letter of each paragraph. He still hadn't decided what he was going to be in the village, but he'd spent time with Dan and the monks as we talked about the monastery.

His story went as follows:

I am the descendent of a great man. His name was Lord Fitzharding. He owned a great estate in the south of England.

He had lots of children and it went well for about three generations but a terrible fate fell the family when a new born son crawled off in a large forest while picnicing on the edge of it.

He was never found but he managed to survive.

A pack of wolves took him in. As he got older he learnt to use a bow and arrows. By the time he was 15, he was able to kill a rabbit at fifty metres away but he never killed more than he needed.

Once while hunting he met a beautiful lady named Maid Marion. She was lost and very hungry. He took her home and gave her the best meal he could make.

The plot reminded me of his ogre story, written two years previously, though this time, interestingly enough, the hero makes contact with another without violence.

The following was his letter to his mother.

Dear Mum,

How are you? I hope you're feeling great. I do.

I have just made it into the monastery and the Abbott is really nice. His name is John and he has made it really easy to move in.

But it is sometimes very hard to get up for prayers at 12 at night.

I have learnt a lot since I joined and made a lot more friends at the monastery and everyone is nice and now I know I can eat every day.

When we have a moment of free time we play lawn bowls or talk.

At the moment I am copying the Bible. I have done twenty-seven pages.

I can hear the dinner bell, so I must go. I'll talk later. Bye for the moment.

Sorry to go, but I was ravenous and I want to give a good impression of myself.

How is dad and the rest of the band? I hope they're great and has dad got over me going to the monastery. I really hope so.

Is John still the page of Sir John? I hope so.

Congratulations on your wedding anniversary.

Please answer all my questions and please excuse all spelling mistakes. I aren't a very good speller.

Goodbye. I'll write more letters later on.

Dan wrote too. His story has been lost, but I will never forget the circumstances surrounding its writing.

He watched some filmstrips on medieval monasteries and village life, and was particularly taken by the sessions on illuminated manuscripts organized by Margaret. He decided early on that he wanted to work in the scriptorium, and in his village folder he drew a very careful and detailed plan of it, complete with labelled compartments for pens, paper, quills, ink and blotting paper. He had plenty of ideas about his character, but was reluctant to write them down. So he dictated his story to Beth, a parent working with us at the time.

When they had finished, Dan put the four-page story into his folder, and didn't look at it again for about a fortnight. Then, after school one day, Dan and his father were making some cardboard bricks, and I was working alongside them. As we worked, Dan told his father about the village.

'I'm going to be a monk, and I'll be working in the monastery?

‘That sounds good,' said his father. 'What will you be doing?'

‘I’m going to copy things, with special pens and ink. I guess we'll try to sell them to make some money. I'm not sure yet. Did you know that the monks had to get up in the middle of the night to go to church?'

'Really!' said Dan's dad. 'What else have you been finding out then, Dan?'

'Just a minute, I'll get my folder and show you.' He came back a minute later, and showed his father the plans for the monastery, the timetable of a monk's day, and talked about the monk’s work. Then he came to the story he had dictated to Beth.

"Here, read this,' he said to his father. ‘It's the story I made up about my medieval life.'

‘Why don't you read it to me, Dan? Then I can keep making these bricks while I listen.'

I looked up quickly. Dan had never read anything as difficult as this before, and I knew that a fraught and stumbling reading of this story could set his morale right back. He was feeling so good about the village at the moment, and I didn't want anything to upset that.

He hesitated for a second.

'Go on,' said his father. 'I'm listening.'

Dan read the first sentence tentatively, and seemed surprised that he had managed it. He took a deep breath, then launched into the rest of it, gaining confidence with every line, and read the whole story from beginning to end with no help from either of us. We both congratulated him, and he looked up from the page, shiny-eyed and triumphant.

Nearly two years later, long after the village was over and after I'd left the school, I interviewed Dan about his time in our class.

‘I remember once I did this bit of writing,' he said, 'and my dad had just come in to make some of these bricks after school and I started talking about it, and I had to read to you and my dad. I was really reluctant. But then I read it, and I read it normally like an adult would read it. I found it really strange when I did that. It was strange how I read just like an adult.'

For me, it was one of the highlights of the whole village project.