This morning I’m going to meander. I like meandering. The story I’ve most often told my students is all about meandering.

And I’m in the mood for distractions. A meandering with distractions. Goodness knows where I’m going to end up.

1.

Last week my son Sol and I went for a day trip to the Gallery of New South Wales.

First we visited the finalists for the 2024 Archibald Prize.

A tiny painting caught my eye, done on some torn brown paper and stuck onto a scrap of used cardboard.

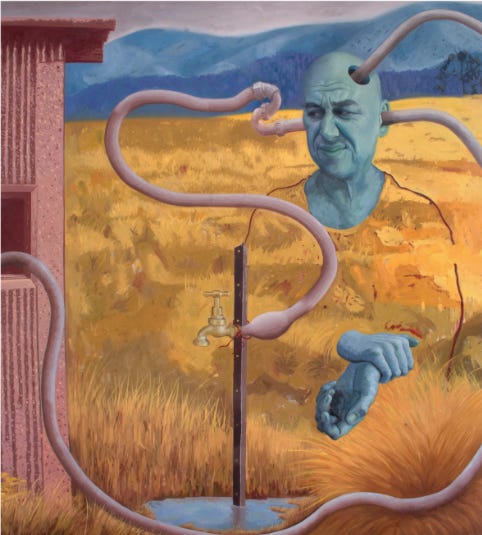

Sol’s favourite was this one:

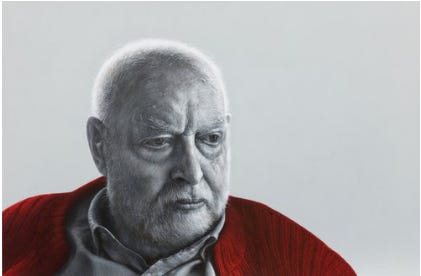

My favourite was the painting of David Stratton, the retired film critic.

2.

Then Sol and I went over to the new part of the gallery, the Sydney Art Project.

In one of its light-filled rooms there was a beautiful installation, its scores of hoof-shaped feet sprinkled with fresh aromatic spices - nutmeg, cumin, cloves, cinnamon and more - so that to walk around the structure was to walk through invisible clouds of scent.

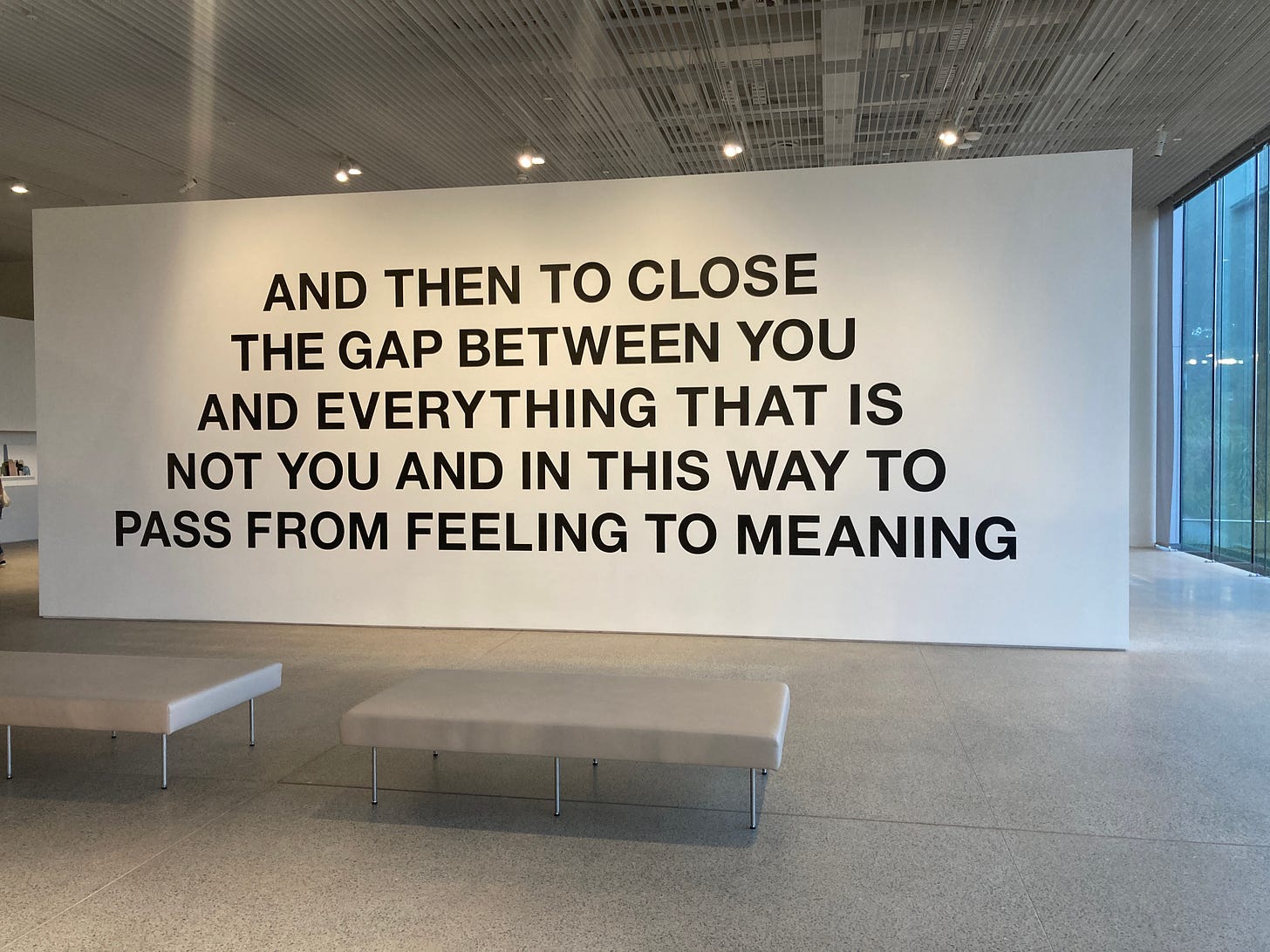

Then we noticed some text on an enormous wall.

Sol and I talked about it briefly. What did it mean? What was its significance here? Who wrote this?

3.

When I got back to Canberra, I thought I’d try to track down its source.

I found it this morning.

The basic project of art is always to make the world whole and comprehensible, to restore it to us in all its glory and its occasional nastiness, not through argument but through feeling, and then to close the gap between you and everything that is not you, and in this way pass from feeling to meaning.

― Robert Hughes, The Shock of the New

4.

I think - if I’m understanding what Robert Hughes has written (and I think it’s complex and that maybe I need to read the whole chapter) - that this is what I try to do in my writing.

The world as I have experienced it, and especially the world of the classroom, is dauntingly complex. Teacherly aspirations jostle with administrative demands and student impulses (to name just three of the many unstable and unpredictable variables). All these dynamic and complicated forces interact chaotically to make the classroom the kind of dizzying world described by David Malouf in his novel The Great World.

Digger was dizzied by the world. He could never, he felt, see it steady enough or at a sufficient distance to comprehend what it was, let alone to act on it…

A nailhead. That was clear enough. Round, flanged, with ridges that allowed the hammerhead a grip. The weight of the hammer, too.

Driving a nail in, feeling the point go through the soft grain to bite on the last two blows - that was the only action he knew that was simple.

Everything else, the moment you really looked at it, developed complications.

Even the least event had lines, all tangled, going back into the past, and beyond that into the unknown past, and other lines leading out, also tangled, into the future. Every moment was dense with causes, possibilities, consequences; too many, even in the simplest case, to grasp. Every moment was dense too with lives, all crossing and interconnecting or exerting pressure on one another, and not just human lives either; the narrowest patch of earth at the Crossing, as he had known since he was two years old, was crowded with little centres of activity, visible or invisible, that made up a web so intricate that your mind, if you went into it, was immediately stuck - fierce cannibalistic occasions without number, each one of which could deafen you if you had ears to hear what was going on there. And beyond that were what you could not even call lives or existences: they were mere processes - the slow burning of gases for example in the veins of leaves - that were invisibly and forever changing the state of things; heat, sunlight, electric charges to which everything alive enough responded and held itself erect, hairs and fibres that were very nearly invisible but subtly vibrating, nerve ends touched and stroked.

This was how he saw things unless he deliberately held back and shut himself off.

(p296 of the Picador edition)

What to do in the face of such complexity?

To hold back and shut oneself off is one solution.

To make art, Hughes seems to be saying, is another.

5.

My writing is my attempt to close the gap between me (and my propensity to be dizzied) and what exists out there in the different educational worlds - primary, secondary and tertiary - in which I’ve worked.

This idea - that to write is to reduce the dizzying gap between me and not me, to pass from feeling to meaning - applies, I think, to the pieces I’ve published here on The Mythopoetic Classroom since posting Newsletter 5.

Chapter 1 The beginnings, Chapter 2 Getting into the mood and Chapter 3 The pace quickens of Part 2 of School Portrait, describe the sometimes tense preparations for the building of the medieval village in our primary school classroom. Each time I wrote about these events - at the time in a journal and later under the beady eye of an uncompromising editor - I had a sense of taking a step or two away from chaotic complexity towards some kind of useable understanding. Or, in Robert Hughes’ words, passing from feeling to meaning.

The story ‘Both Alike in Dignity’. This story had its genesis in distressing and confusing complexities. A preservice teacher I was supervising had inadvertently got himself into significant hot water. Three of his colleagues - my co-authors - worked with me, some months after the event, to make sense of what had happened, and to share chaotic moments they themselves had experienced as they taught their first classes. Again, the process of writing the story was a process of making some order and meaning out of the often chaotic and always complex experiences of the beginning teacher.

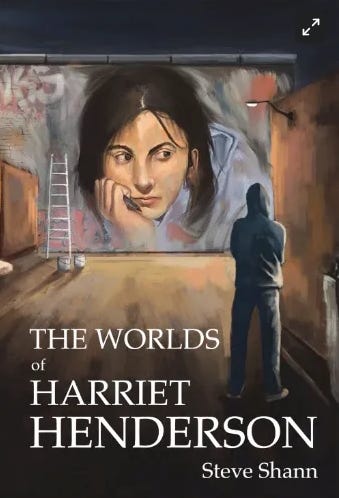

The Worlds of Harriet Henderson Part 1 Chapters 6 and Chapter 7. These are chapters which (amongst other things) describe tensions in a staffroom. They were written in the year after I’d been accused of unethical behaviour towards two colleagues and during which I’d felt incensed by a lack of support from the executive. I felt a mixture of fury and despair at the time. It felt good to perceive it all from a more distanced perspective.

(Perhaps, by the by, the move from feeling to meaning is particularly evident in the story I published last month: Anguish and the urge to know.)

6.

This post has become a kind of meditation on how, through writing, I’ve attempted to create a usable perspective, a more coherent meaning, out of some raw experiences. To close the gap between me and everything that was not me. To pass from feeling to meaning.

And I find it interesting to imagine that this is at least a part of what is happening in the painting at the top of this post. The painting is called Pressures Build, another of Sol’s paintings.

There are some words that Sol submitted with the painting when he entered it for a competition a couple of years ago.

A flow from an unknown source. The square black hole in a solid shed? Or an anxious brain?

Pressures build. Slowly. Tensions mount.

Indecision. Paralysis.

The big moment is still to come.

Turn the tap? Or wait? The helpless hands cannot agree.

The breeze shifts the summer grasses, the blue hills wait.

Am I witness or agent?

I do not know. I do not know.

I love this stuff, Steve - the concept of meandering and the meanderings themselves. My favourite picture is the scrap of paper on card. I find it exhausting trying to find meaning. Now I just mostly observe. Yesterday I spent 10 minutes, sitting in our summerhouse while trying to write a TV script, (desperately trying to discover and express meaning) contentedly watching a muster of gnats trampolining in the air above the pond.