1.

It’s a cold Canberra winter morning in the early 1990s. I’m sitting in my consulting room (I’ve recently trained as a psychotherapist), and opposite me is Joseph, fifteen years old, son of a diplomat, brought to me by a mother worried about her son’s somewhat alarming behaviour at school.

The conversation is unsettling. Joseph seems bemused. As if his mother’s alarm is faintly ridiculous. As if my first questions are unnecessarily intrusive.

But if what his mother has told me is true, there is most definitely something to be concerned about. How to explore it, though, when Joseph is telling me that all is well?

His responses to my questions skim across the surface.

I decide to change tack. ‘Tell me a story,’ I say. ‘Pick any of the figures you see on my shelves, arrange them however you like on the carpet, then tell me a story about the scene you have created.’

He looks mildly surprised, and perhaps relieved that we’re not going to just talk. He picks out some figures, arranges them on the carpet, and then tells me a story. I type as he speaks.

There's the evil and the good, and between them is the sea and at each end of the sea there are two boxes of mystery. At one side of the sea there are the good things, the sweet smelling, the comfortable and the good ruler. On the other side, there is the evil and it's all enclosed in bushes, a sense of not letting the rest of the world know what's going on inside. There are the sour smelling things, the funny and evil kind of things, and an evil kind of a ruler. And also on the evil side there is a part that the good side has conquered, and its armour is being taken off and it is being exposed and converted to the good. And in the middle of the sea, and between the two sides, there is a sun which is a meeting point, not very high where neither will fight, like a conference area where they talk.

As he tells me the story, I feel increasingly excited. I'm particularly taken with the relationship between the two worlds and the hints that the good will prevail.

He finishes and we sit for a moment in silence.

I’m suddenly at a loss for words.

“A wonderful story,” I say. I sense that more is required of me. But what?

I have no idea.

I’m affected, that’s for sure. And my training and my reading of Jung, Bion, Winnicott and many others, reassures me that this is a necessary stage.

But what now?

2.

I tell my supervisor, Giles Clark, a Jungian analyst based in Sydney, about the encounter with Joseph. I read the story out loud to him.

I first met Giles when he gave a workshop over several weekends about Jung’s philosophical ancestors. It was a truly wonderful experience. With untidy bundles of notes that kept slipping out of his hands, he kept spellbound the dozen or so of us sitting in a colleague’s living room. His presentation was erudite and clear. I still have the notes.

I was thrilled when he agreed to be my supervisor.

3.

Giles listens to me read the story. How did I feel, he asks. What did I think?

I told him I thought the story was stunning. I said that it seemed to have within its narrative hints about what was going on beneath the surface for Joseph but that I was struggling to name them. I told him how confused I felt when Joseph retreated after telling me the story, and seemed more interested in talking about the tree outside my window than about what was happening in his life.

I was wanting Giles to help me understand the meaning of the story, and how best to respond. He wanted me to talk about my confusion.

Then, one day, we had the following conversation.

GILES: … all your wondering about aspects and essences, about whether you think about things in the right way, whether you're being effective or not, about feeling useless and wanting to be more active ... Spinoza has things to say about all of this, good things Steve...

STEVE: Go on Giles, I'm all ears. What's he saying about these things?

GILES: This is a very large subject, not easily entered. But let me try. Let's see where we get to… You've said to me before that you have this sense, Steve, that to think about individual bodies and minds …. yours, Joseph’s … is too limiting ... and at the same time that when you start to think more globally, more philosophically if you like, your ideas tend to float upwards and out of fruitful contact with your experienced world.

STEVE: Or like I'm living in this psychic chamber with my thoughts bouncing off the walls and never reaching the outside.

GILES: Spinoza looks at things globally, but also minutely. He talks about the nature of the world on the one hand, and he talks about the relationship of our thoughts to our bodies on the other.

STEVE: Say more.

GILES: Spinoza says that there is only one real thing, only one substance, that the ‘beings' we experience as separate - people, animals, trees, rocks, clouds, rivers - are modes of this one substance ...

STEVE: Modes? Meaning that all these things are the forms in which we experience God.

GILES: Something like that. God is all there is, and therefore nature is another word for God. He talks about 'nature naturing', that's what happens, that's all that happens...

I found much of this puzzling, alien to ways of thinking I’d come to adopt.

But I began to read some of Spinoza’s work. And some commentaries. Every now and then Giles would say some more about him. And I began to see things - my work with Joseph and others, and then my teaching life - differently.

I wrote my PhD thesis on the story of Joseph and on my conversations with Giles. I intend to publish the thesis in full here one day. It’s a good story, I think. Important for me, at the very least.

4.

A few years after my encounter with Joseph, I returned to the classroom. My teaching colleagues would ask me if I thought that being a psychotherapist had influenced the way I taught. At first I doubted it. Classrooms were such different environments. But it wasn’t long before I began to see an influence.

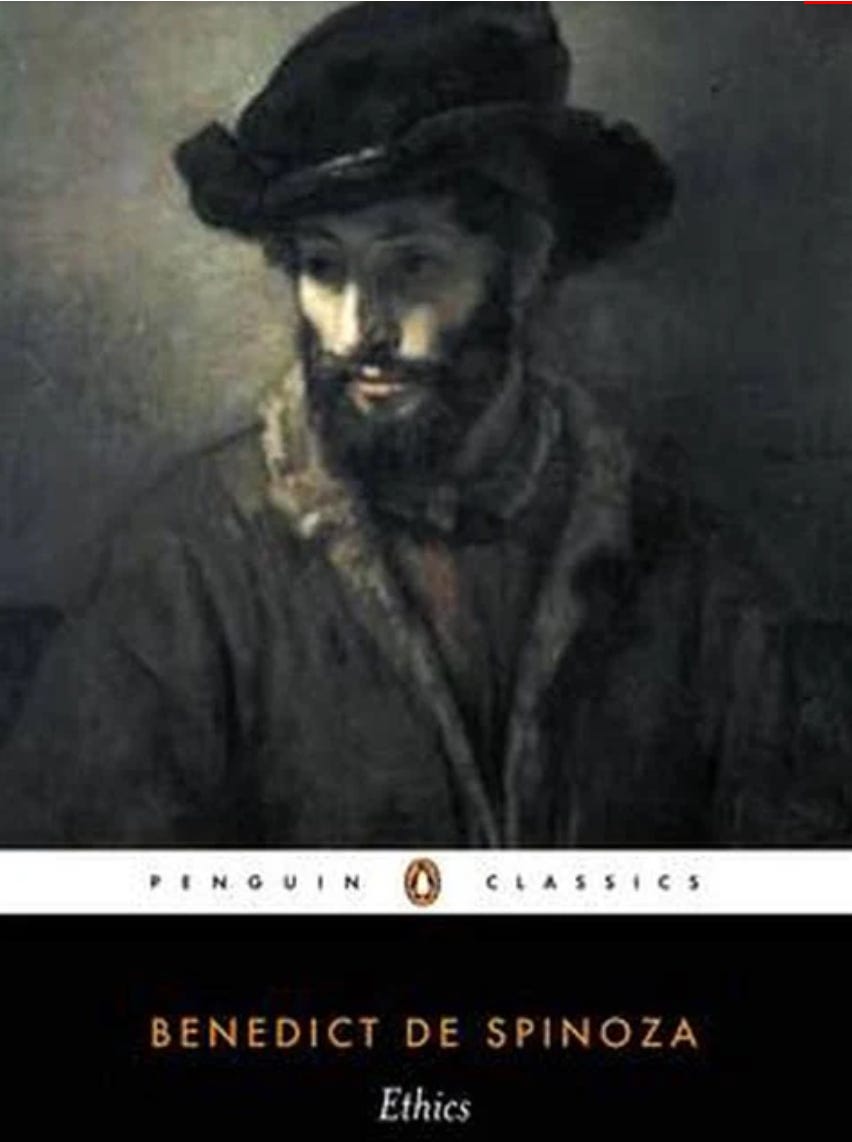

In the post On the natural laws governing learning, I have told the story of the weekend when I tried to channel Spinoza and how this gave me a more potent way of thinking about teaching and learning,

As an academic I wrote (with colleagues) an article called A love towards a thing eternal: Spinoza and the classroom which views both conversations between preservice teachers and then the drama of a Year 10 English class through a Spinozian lens.

5.

After I’d retired from the university, the principal of Macquarie Primary, the extraordinary Wendy Cave, asked me to sit with groups of teachers and LSAs (Learning Support Assistants). She wanted me to listen to them talking about their work and their students, and then for me to write three stories drawing on the material.

The first of these - The Ant Colony - doesn’t mention Spinoza. But Spinoza’s way of thinking - or at least Steve Shann’s interpretation of Spinoza - permeates the story. When I reread the story now, I imagine each being - each teacher, each student, each ant, each staffroom, each ant colony - as a mode of the one substance, each with an inbuilt urge (sometimes successful, sometime not) to connect with other modes.

I see natura naturans. Nature naturing.

6.

Harriet, the main character in my novel The Worlds of Harriet Henderson, describes in her private journal a moment, both exciting and awkward, with her new English teacher Molly McInness.

We had English just before lunch, and after everyone else had left I asked Ms McInness if she had a moment. Sure, she said, and we sat at a desk by the classroom window in the winter sunlight.

I told her about wanting to be a writer, and asked if she would be able to give me some help.

She’d love to help, she said. What did I have in mind?

Suddenly I felt tongue-tied. I think I blushed. I think now, looking back, I had no words because in fact all I had in mind was having an excuse to sit with her one-on-one. (I’m trying to be honest here, though I can feel myself reddening again as I write these words.)

There are many ways such a moment might be read. Some kind of Freudian reading, for example. Or a slightly awkward and embarrassing adolescent crush perhaps.

But for me, and I’d like to think for Giles and Spinoza too, what is happening here is no different from a river finding its way to the sea, a worker bee setting out on a foraging expedition, a planet following its orbit around a sun. It’s nature naturing. It’s the urge in every living thing to interact with other living things to become more of what it essentially and potentially is.