On the natural laws governing learning

An experiment, written in 2000, when I was facing something of a crisis in confidence on returning to teaching

“Fame has also this great drawback, that if we pursue it we must direct our lives in such a way as to please the fancy of men, avoiding what they dislike and seeking what pleases them. . . . But the love towards a thing eternal and infinite alone feeds the mind with a pleasure secure from all pain.” Spinoza

Preface

Down at the coast by myself in the year 2000.

Feeling shaky.

Possibly feeling, with Spinoza looking over my shoulder, that I might be directing my life in such a way as to please the fancy of folk, avoiding what they dislike and seeking what pleases them. Wondering what a love towards a thing eternal and infinite might actually mean, given my circumstances.

I’d recently returned to teaching at the age of 53 after a break of around ten years. It had turned out to be more difficult than I expected. After a couple of terms of pleasurable dabbling, I’d begun to want to be a serious teacher again, and found myself surprisingly uncertain and self-critical.

Too much of the time I didn’t feel as confident as I ought about my classroom practice. I’d find myself speaking to students and classes in ways that didn’t sit easily with the image I had of myself as a teacher.

On top of this (and probably related) was an inarticulateness in discussions with other teachers about educational matters. I’d written quite a lot, but there were been times when I was uneasy about a direction a conversation was taking and was unable to find the words in my mind (let alone out loud in the discussion) to express whatever it was I was feeling. I wondered at times if too much water had passed under the educational bridge while I was elsewhere.

Perhaps I couldn’t speak because I no longer knew this river.

This became something of a crisis in confidence. Didn’t I know anything any more? What had happened to the solid centre I once thought I had?

The trip to the coast was an attempt to wrestle with some of this.

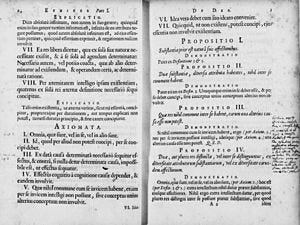

Spinoza

For some years I’d had a developing interest in the philosophy of Spinoza. There’s much of it I didn’t understand. But two aspects of it spoke to me. They were

the way Spinoza links human behaviour and ethics to a metaphysics about God and the nature of the world, and

his attempt to uncover reality through the exercise and reason and a mathematical logic.

The first of these, the link between the micro and the macro, had always been right up my alley. I’d always enjoyed (indeed in a sense needed to) think about the detailed (eg. classroom practice) in terms of the global (eg. educational philosophy). My way into teaching was through the ideas of A.S.Neill and people like John Holt, both of whom attempted this marriage.

But the second, the emphasis on discovering truth through the exercise of reason, was not me at all. I’m an intuitive, rather than a logical, thinker.

Yet it was to the logic of Spinoza that I was drawn during this crisis week at the coast.

To begin with I re-read some of his writing and some of the commentaries, while at the same time trying to write about my lack of confidence.

Then, one night, I had the idea of trying to write something ‘in the style of Spinoza’, partly for fun and partly because I had a feeling that one way of rediscovering some solid ground might be to subject some of my intuitions to a closer rigorous and rational examination.

I scribbled late into the night and for much of the next couple of days.

The result is the following rather bizarre document, written at times with tongue in cheek, but also with growing enthusiasm for the solidity this method seemed to be giving me.

PART 1. Learning as belonging to nature

Preface

Definitions

I. Learner: I’m defining learner here as any person engaged in the business of learning (see definition below). In order to draw attention to the ‘naturalness’ of the act of learning, there are times when I shall be calling a learner ‘an organism’. In order to remind us that we’re functioning in a school, there will be times when I’ll call a learner ‘a student’. These three terms – learner, organism, student – are here by definition interchangeable.

II. Learning: I understand by learning a natural process by which the learner or organism, through the engagement of his body/mind with other body/minds, becomes more what he essentially (or potentially) is. Learning, then, is to do with expressing the essence and enhancing the power of the learner.

III. Natural: I am not using the word natural to mean either ‘easy’ or ‘happens by itself without interference or the involvement by others’. Instead I’m using the word in a more biological or environmental sense, to mean ‘being a part of the natural world’. Learning is the result of an inbuilt natural tendency or urge in the organism to attempt to increase in its own being or essence or power. Learning, then, is natural for a student in the same way that growing is natural for a plant.[1] Given favourable conditions (which are always a highly complex web of different factors), learning takes place naturally; given unfavourable conditions, learning (like growing) struggles (and becomes learning of a different type) or stops (the organism dies).

IV. Teaching: By teaching I mean the way a teacher organises the environment (which includes herself) to enable students to learn.

Propositions

PROP 1. Learning belongs to nature.

Proof: This is self-evident from the definition (Def II and III).

Note: The move to remind ourselves that learning belongs to nature is a part of the much bigger issue of where to position human beings and human nature: are we a part of nature, subject to all the natural laws, or do we have our own set of laws because we sit somehow above or outside of the natural world? The historical and scientific evidence says that without question we’re descendents of the apes and that our bodies turn to soil after we die (to become nutrients for other aspects of nature). The arguments put forward here are based on the self-evident fact that we belong to nature and that therefore our learning is a natural function of our being.

Many misconceptions and difficulties follow from our inability to understand this clearly.

We assume that learning is something that must be learned. The current catch phrase ‘learning to learn’ expresses this succinctly, and it is based on the nonsensical twin assumptions that children arrive at school without any experience of learning and that in order to learn we must be taught what learning is all about. No one needs to learn how to learn in order to learn.[2] Learning does not have to be learned. It is a natural act, and cannot be avoided.

But because we have it in the back of our minds that learning is an unnatural act (ie. that learning doesn’t belong to nature), we teachers see it as integral to our role that we find ways to ‘make it happen’. Or we divide our classes into those who seem to ‘take to learning naturally’, and those who don’t (and who must be cajoled, bribed, persuaded, seduced etc).

However, if we understand that learning belongs to nature, then we begin to see classrooms and learning more clearly. We withdraw time and energy from activities designed to ‘bring horses to water even if we can’t make them drink’ (detentions, moral cajolings, appeals to their future interests, notes in diaries, phone calls to parents, grades, marks) and instead concentrate on vigorously playing our part in the natural learning environment, as role models, ‘walkers-of-the-talk’, guides, providers of resource materials, challengers, adversaries, thorns-in-the-flesh, link-makers, experts and fellow enquirers.

Remembering that learning belongs to nature not only changes how we are in the classroom; it also effects what we teach. We’re more likely to feel at ease allowing students to express their own preoccupations and perspectives and natural reactions, to see their responses as being at the heart of the curriculum. We’re less likely to give in to the pressure to ‘move on’ because there isn’t time, given the requirements of the curriculum, to explore these student perspectives.

PROP 2. A learner-organism has an inbuilt urge or necessity to exist.

Proof: This is obvious. The alternative, that organisms do not have an inbuilt urge or necessity to exist, is absurd, as nothing would then explain why they move to incorporate those external objects necessary for their existence: sunlight, food, water, shelter, safety, a mate, etc.

PROP 3. An organism is always a part of another organism.

Proof: Again this follows inevitably from what has already been established. An organism, in order to satisfy its inbuilt urge to exist, makes relations with other organisms. This sets up complex webs of interconnection and interdependency, familiar to us all. No organism exists as a self-dependent entity. Every organism is a part of a much bigger web, which is itself an organism.

Note: Is a student the fundamental organism we teach, or is it the group of students that we call a ‘class’? Is it the mind of the student (and his body is his own business, and that of the PE staff), or the whole person? Or perhaps the fundamental unit is the student/teacher dyad? Or, in the case of team teaching, a group of teachers with a class? Or a family? Or the school which is the organism, of which the student is a part?

The point of this apparent diversion is to suggest that what we’ve said about organism-learners applies to these other organisms as well. The class has an inbuilt urge to exist. So does the teacher-pupil dyad. The natural laws that I’m outlining in these propositions apply to all organisms. Many implications follow from this, which I will explore later.

PROP 4. Nature is always a highly complex and dynamic set of inter-relationships.

Proof: The inevitable connections between organisms (see Prop 3) must necessarily be dynamic (an organism is born, grows, changes, and dies and each of these changes effects the surrounding organisms with which the mutating organism has relations) and complex (because the interconnections are so huge and the changes so constant).

PROP 5. The learner naturally develops the capacity to adapt.

Proof: Because the learner-organism has an inbuilt urge to exist (Prop 2), and because it is a part of a dynamic natural world (Props 3 and 4) the organism must learn to adapt to changes around it.

Note: This, as we shall see, has positive and negative aspects, so far as classroom learning goes. The learner will adapt to whatever is going on in the classroom, in ways that are intended to further the learner’s learning but which may in fact do more for the teacher’s ego.

PROP 6. The inbuilt urge necessarily involves others.

Proof: This follows from Prop 4 and Prop 5.

Note: We know this from our empirical observations, even though we sometimes speak (and think) as though learning were a solitary activity (‘Now go off to a quiet space and really learn this stuff!’) Those who spend huge amounts of time alone tend to do one of two things: they either invest enormous amounts of energy (and considerable ingenuity) trying to break through into some spectacular connection with the outside world, or they retreat deeper and deeper into a solipsistic world of their own creation with increasingly more fragile links with other people. In the first instance, the learning becomes more and more desperate (and occasionally spectacularly successful), and in the second the learning tends to become more and more a part of a self-imposed self-sufficiency that leads to chronic loneliness, mental illness and sometimes in early death. This is why we become concerned at those students whose natures or experiences (usually the latter) have turned them away from actual relationships and towards an almost exclusive pre-occupation with the sanitised and superficially-less-problematic world of cyberspace.

PROP 7. The impulse to learn is to attempt to know better (to feel more deeply) the connection between me and non-me.

Proof: Learning being the natural consequence (Prop 1) of the inbuilt urge to exist (Prop 2) in a world that necessarily involves relationships with others (Prop 7), the impulse to learn must inevitably be about the connections (the relationships) between that organism (me) and everything (animate and inanimate, material and ideational) which is other (non-me).

Note: From the very beginning of life, the baby is exploring, influencing and adapting to the non-me world.[3]

In our classrooms this is replicated by the students going through a stage, often unconsciously, to ‘work the teacher out’, to find areas of mutual interest or responsiveness, to see what gets a reaction or how to get approval. There’s both an exploration of the me/non-me intersection going on, and an attempt to find ways (negative if the positive doesn’t seem possible) to animate the relationship.

This exploration of the relationship between the me and the non-me can take quite primitive and unconscious forms in the classroom. Teachers are familiar with the ritual ‘boundary testing’ at the beginning of a school year. A prominent psychiatrist (Winnicott) describes this process as being a feature of all human relationships, the attempt by the ‘me’ to destroy the ‘non-me’, hoping all the while that the ‘non-me’ will be strong enough to survive the attack and therefore prove itself worthy of the ‘me’s’ love. By this process, says the psychiatrist, the ‘me’s’ world is expanded to include the ‘non-me’. The survival has resulted in a real relationship, which in turn leads the ‘me’ to have an enhanced experience of a bigger and more powerful world.

PROP 8. No organism survives without the capacity (intelligence) to learn what is necessary for the development of its essence and its adaptation to the ‘non-me’ world.

Proof: This is just the corollary of Prop 5.

Note: This is the challenge for educators.

If it is true that survivors all have the capacity to learn what matters to them, why do so many of our kids do poorly at school? Is it perhaps because, for many of the students, we’re focussing on the wrong things, or teaching in inappropriate ways? How can we organise our classrooms so that this capacity/intelligence is developed, engaged, harnessed?

As things stand at the moment, it’s not a challenge that we’re taking up particularly rigorously. Instead we tend to fall back on the myth (and the point of these logically-connected system of propositions is to show that it’s a myth, that the myth has no rational or logical foundation) that some students have it – the intelligent ones – and others just don’t cut the mustard … and that, in order to keep standards high, we need to direct our attention towards the former.

The popular educational research these days – Howard Gardner, Julia Aitkin et al. – is telling us that our division of students into the bright and the not-bright is limiting us, that there are many different kinds of intelligence (Gardner) and many different thinking styles (Aitkin) which can be used as doorways to deeper learning for more students. Yet how often do we hear that x isn’t all that bright or that of course the reason y is struggling is that he’s not particularly clever? These attitudes are dated and the tenacity with which they continue to underpin our educational discussions is a major stumbling block to true learning.

PART 2.Learning as an activity directed towards power

Preface

Definitions

V. Body/Mind: By this I’m drawing attention to ‘two sides of the one coin’, where often (and misleadingly) we think about the body/mind as if it were two separate things. A learner is an individual with a body/mind. This body/mind can be seen in two different ways, viz. the learner can be perceived as a body which has ideas, and it can be seen as a mind which expresses itself bodily. The implications of the use of this term will be explored below.

VI. By power I mean the individual’s capacity to be active, to be effective, to create effects, to be an agent. The opposite is to be passive (or powerless).

Propositions

PROP 9. To learn is to act.

Proof: To learn involves relationship (Prop 6) and adaptation (Prop 5). This cannot be passive. Therefore it follows that to learn is to act.

PROP 10. To act is to have an effect.

Proof: Because an organism is always a part of another organism, any change in us (adaptation) must necessarily affect a change in the organism with which we are in relationship. Therefore to act is to have an effect.

PROP 11. To learn is to have an effect.

Proof: This follows immediately from Props 8 & 9.

PROP 12. To learn is to become more powerful.

Proof: To learn is to act (Prop 9), to have an effect (Prop 10), which means to be an agent. Therefore to learn is to become more powerful (see Definition VI).

Note: By now the reader may be saying something like, ‘Hey, just a minute! The learning I see going on in my classroom or in yours doesn’t necessarily make the learner more powerful!’

This is precisely the point of this writing. I’m not saying that everything that is called learning is part of a natural process and results in the learner being more powerful. Instead, I’m saying that much of what we call learning isn’t learning at all, and that to judge whether or not something is genuine learning we must ask ourselves if it does make the learner more powerful in the ways I’ve been outlining here.

Too often our logic has gone something like as follows: Learning is good for you. Classrooms are set up in order to facilitate learning. Therefore what goes on in classrooms is the type of learning that is good for you. This is not good logic, has led to lots of fuzzy practice and the bolstering up of the fuzzy practice by extraneous sticks and carrots.

What I’m wanting to draw readers attention to here is the nature of true learning. We get (I get) into conceptual and practical tangles by trying to justify/promote false learning.

PROP 13. To learn is to become more developed in what one already is. The learner’s essence is enhanced.

Proof: If an organism (learner) is always a part of other organisms (Prop 3), and if through learning the organism becomes more powerful (Prop 11), then it follows that the organism’s individuality (his essence – See Def V) is enhanced. Thus to learn is to become more developed in what one already is.

Note 1: But what about those cases when the organism loses its individuality in its relationship with the bigger organism? This of course happens, as when an insect is eaten by a frog, the frog is eaten by a Frenchman, or the Frenchman dies for his country in the trenches. This also happens in classrooms, when a student becomes a part of a mob mentality (and is lost in the student body) or becomes over-anxious to please the teacher (and is lost in the teacher body).

Again, these examples simply reinforce my point about the difference between true learning and false learning. True learning, by definition, enhances the individuality or essence of the learner. If the essence hasn’t been enhanced, true learning hasn’t taken place.

Note 2: How profoundly this differs from the common view in its implications about what education is about! Now we come to see more clearly the point of this careful consideration of definitions, propositions and proofs. For we now begin to see that the purpose of education is to develop something that is already present, that the student brings to the classroom an essential individuality that is at the heart of the educational project.

It is for this reason that a learning environment must make room for the experiences and perspectives of the students who learn in it. This means going further than asking them what they think of the materials that we introduce. It means taking seriously questions like, ‘What has this got to do with me?’ and making clear and conscious connections between the actual experiences and preoccupations of our students and the curriculum. Different teachers will do this in different ways. Some will take the students’ experiences as a starting point. Some will make connections as they introduce their material. Others will sit confidently in the knowledge that their material is vitally connected to the present needs of their students, and will draw the students into their confidently constructed learning environments without ever mentioning an explicit link with the students’ lived lives.

What teachers won’t do is imagine that education is all about filling empty vessels (none of the students is empty) or lighting fires (there are burning issues preoccupying even – perhaps especially – the most lethargic). Both of these are familiar metaphors in the educational literature, and both are inadequate. I’m suggesting that the extended metaphor I’m using here – to do with nature and interconnected organisms – provides us with a surer footing for our educational practice.

PROP 14. There always exists a connection between the learner’s essence and his learning.

Proof: The essence is engaged and developed in learning (Prop 12), and it follows that without the engagement of the essence (or individuality) of the organism-learner, there would be no learning. Therefore the essence and the learning are always connected

Note: This will be clearer if we understand ‘essence’ not as a noun but as a verb. An essence isn’t a thing; it’s a process. Indeed the essence is the process of expressing and developing the individuality of the organism, and for the reasons given is therefore what drives (or causes) learning. The only reason I don’t say ‘the essence is the same as the learning’ is because the notion of ‘individuality’ is attached to ‘essence’, and so by making a distinction between the terms, I am reminding the reader that the way one organism enhances its essence (learns) will look quite different from the way another does.

PROP 15. This connection between learning and essence exists in the learner’s body/mind (Def 2:V).

Proof: The organism is the place where essence (which has its roots in the ‘me’ world) and learning (which has its branches and leaves in the ‘non-me’ world) intersect, or have their relationship, or are connected. (These terms are here synonymous.) This is clear from Props 1 – 13, especially Prop 7.

The body/mind, then, is like the trunk (though in some ways the image is too concrete).

Note: It is perhaps time to look more closely at the meaning and significance of the term ‘body/mind’.

Nearly 400 years ago Descartes made popular his notion that body and mind were two separate things, and the world – the educational world no less than other parts – has suffered the results of this misconception ever since. Despite Shakespeare (whose psychological dramas took place in body/minds, never either one or the other) and all good novelists since, despite Spinoza (who countered Descartes’ thesis explicitly), despite Nietzsche, Freud and Jung (who all in their insane and highly original ways demonstrated beyond question the existence of unconscious layers of the self which manifested themselves both in the body/mind – see again Def IV), we continue to behave as if our learners have bodies (which need to be exercised and are the domain of the extra-curricula program) and minds which need to be stretched (which is the day-to-day business of classroom teachers).

Educational research is lending its weight to the rediscovery of our body/minds. It talks about kinaesthetic, auditory and visual learning, thereby making an explicit connection between body and mind. (‘Learning needs to take place in bodies, and there are three entrances!’) Links are being made between music (is that body or mind? it’s an absurd distinction) and memory, between fitness and intellectual capacity, between babies secure at the breast and learners contentedly and confidently gobbling up the curriculum.

We are ever tempted to think of the students in our classes as either engaged (and probably disembodied) minds or unengaged bodies. To begin to think of learners as body/minds opens up new perspectives. Why does my Year 7 class engage better with Treasure Island when they do some drama? Why does reading aloud (well) a passage from a book or a piece of creative writing in front of a room full of other body/minds do something (more powerful? more permanent? more exciting? more satisfying?) that a silent reading doesn’t do? Why do my Year 9’s (and I) like Baz Luhrmann more than Zeferelli? Because our bodies are engaged, along with our minds … or, to put it more accurately, it’s our body/mind that is engaged, which is a more natural and real and powerful system than unminded body + disembodied mind.

Perhaps above all, the concept of the body/mind immediately makes room for the existence of the unconscious, perhaps the concept most unfortunately neglected by educational theory. Boys have reactions (to teachers, to texts, to each other, to events) which they can’t articulate in words but which are expressed in their (lethargic, angry, anxious, non-committed animated, focussed, excited) bodies. Writing, so often an activity that professional writers see as a voyage to discover what it is that lies buried in the unconscious self (‘I write to find out what I do not know’), is seen in our rationalistic culture as something we do to express what we already know. That which lies beneath the surface of our consciousness, information or pre-conceptions which can only be expressed with frowns, sighs, desperate threats to give up, day-dreamings or dreams – so often hold the key to our next steps in learning. If we could train ourselves to relate to body/minds more, rather than to just minds, we’d be given doors into these vital experiences.

PROP 16. Learning changes the world (of the organism and of the bigger world to which it is connected), and the changed world requires different kinds of learning as a result.

Proof: To learn is to become more powerful (Prop 12) and is to have an effect (Prop 11), which means that both the organism is changed (Prop 13) and consequently the system to which the organism belongs is changed (Prop 3). Therefore the world (of the organism) is changed. It is essentially different, its essence or individuality has changed, and there is always a connection between the learner’s essence and his learning (Prop 14). The changed world needs a different kind of learning for the new conditions it finds itself in.

PART 3.Learning as an activity directed towards mating and animating

Preface

Definitions

VII. Intelligence: I understand by intelligence the capacity of the individual to employ his essential faculties in order to become more powerful.

VIII. Pleasure: By pleasure I mean the emotion experienced from having our impulses gratified.

IX. Pain: By pain I mean the emotion experienced from having impulses frustrated.

X. Perfect: By perfect, I mean complete, itself without the need of anything extra. In this sense the only thing that is perfect the totality of all that exists – what Spinoza called alternatively God or Nature. Every other organism belongs to another organism (Prop 3), and is incomplete – imperfect – without it.

XI. Pathological attunement: By this I understand the process by which a student becomes motivated (see definition above) to please the teacher rather than learn (see definition above).

XII. Projection: By projection, I understand the psychological mechanism by which one person (eg a learner) attempts to alleviate the stress of negative emotion (such as anxiety) by making another person (eg a teacher) feel the same emotion.

Propositions

PROP 17. Learning involves activity. It is never a passive process, but always excites or animates.

Proof: Learning is always active (Prop 2:8), always increases power (Prop 2:11), and must therefore necessarily change both the organism and any organism of which it is a part. Another way of saying this is to say that learning excites (ie makes more active) and animates (increases the energy) both itself and those organisms with which it has a relationship.

Note: These things have already been established in the first two parts.

PROP 18. The organism-learner is innately relational, ie it has a natural tendency to form relationships with other organism-learners.

Proof: This has already been established (Prop 1:6, for instance).

Note 1: The purpose of this wording is to draw attention to the natural tendency towards the establishment of relationships (eg with other learners and with the teacher). This exists irrespective of the conscious or apparent attitude of the other students or the teacher.

Note 2: The existence of fundamental urges has been a perennial preoccupation for philosophers. What is the life force? For Jesus it was love, for Spinoza God (or Nature) acting through the laws of human nature, for Schopenhauer power, for Nietzsche the will to overcome, for Freud sex and for Jung the operation of both the personal and the collective unconscious. In some of these philosophies, the implication is that the life force comes from the inside, is individually generated, and this led Wittgenstein (amongst others) to complain that too much philosophy had been the result of lonely brooding men contemplating the rather empty chambers of their isolated minds (he could talk!). Recently the Jungian writer Giles Clark has coined the phrase ‘the relational urge’, to draw attention to the way our life force is always to do with relationship with others.

PROP 19. The organism-learner is innately expressive.

Proof: The organism has a natural tendency to make itself known, to have an effect, to elicit responses from other organisms (see Props 1:6, 1:7, 2:10, 2:11, 3:15). Therefore the organism-learner is innately expressive; it has a natural tendency to make its essence known and felt.

Note: Again this has important implications for the classroom. Students want to express themselves, want to make an impact on their fellow-students and on the teacher. And they want to do this in a way that feels authentic to themselves (their individuality, their essence). How to do this in a classroom with 30 students in it is a major organisational problem, and yet some way must be found for true learning to be taking place. Our experience is too often of a group of students being present only with a (non-essential) part of themselves, and certainly not with their body/minds, and as a result not making a connection with whatever the curriculum might be in any substantial or permanent way.

PROP 20. Learning always involves the emotions. Pain and pleasure are inevitably involved.

Proof: We seek to animate and effect other organisms (see Prop 11) but we cannot control them (they too are organisms seeking to enhance their own essences which are different from ours). To the extent we successfully mate with other organisms we experience pleasure (see Def 3:2 above), and to the extent that our matings are frustrated because other more powerful organisms have a different agenda from ours we experience pain (Def 3:3 above).

There are also pleasures and pains involved in the roots of our learning experience, the ‘me’ world. To the extent that we can satisfy our urge to express our essence (Previous Prop), we experience pleasure. To the extent that this is frustrated, we experience pain.

Note: It is sometimes implied students will learn if the task is pleasurable and avoid the task if it is painful, and that therefore learning must be made to be fun. It is also frequently and accurately observed that such an attitude leads to a trivialising of learning. Pleasure and pain are both inevitably involved in learning. We strive to enlarge our ‘me’ worlds both because of the pleasures offered by the ‘non-me’ world (enhanced power, greater capacity for expression, deeper insights into our own natures, the pleasures of love, and so on) and because of the experienced pains of the ‘me’ world (loneliness, feelings of inadequacy, lack of confidence, a feeling of being powerless or rudderless, frustration that things don’t work or make sense, etc). These pains are just as important as the pleasures, and when we fail to make room for them in the classroom (ie when we fail to allow for the expression of pain, of the negative – of complaints, for example), then we condemn the learning to the sort of trivialising or superficiality or non-permanence that often bedevils our teaching practice.

PROP 21. These pains and pleasures are experienced by both aspects of the body/mind.

Proof: Given that the learner is an individual with a body/mind (Def 2:V), and that the body/mind is the intersection between ‘me’ and ‘non-me’ (Prop 2:14), and that the body/mind is one substance and not two (Def 2:V), the only place where pleasures and pains can be experienced is the body/mind.

Note: Why is this an important or helpful point to make? Because as teachers we tend to forget that the external signs of whether true learning is taking place is not just in the mind (and how the intelligent mind responds to questions and tests) but also in the body. The withdrawn student is expressing something as much as the animated one; the former that his urge to learn is being frustrated, the latter that his urge to learn is being satisfied.

Our gut reaction to the withdrawn student is too often that he is unable to learn – more about this later – or that he is unwilling to learn, or that for some reason his mind simply isn’t engaging. We see the sullen-ness as evidence of a lack of ability or willingness, when in fact it is a sign of a mismatch between the learning environment we’re attempting to create and the student’s urge to learn. It is true that we cannot make our learning environment fit the learning needs of every student in our class at every moment. It’s nevertheless important not to misinterpret the signs, to recognise them for what they are (our necessary and understandable failure to engage with a particular individual’s natural urge to learn). The teacher is, in this case, the organism with more power to adapt and relate; if the situation is to be turned around, it is primarily the teacher’s responsibility to act.

PROP 22. The mind/body of the organism perceives aspects of the ‘non-me’ world as having a perfection or completeness it lacks.

Proof: The organism-learner has an inbuilt necessity to exist (Prop 1:2) but cannot do so without other organisms (Prop 1:3). Therefore it must satisfy its need to exist by recognizing in its body/mind[4] the relative perfection of the organism with which it desires a union.

We are impelled to learn partly through our painful experience of the inadequacy of the ‘me’ world (see note to Prop 3:18). We are drawn to the ‘non-me’ world to ‘fill the gap’ by our intuitive knowledge that the ‘non-me’ world holds the key to the completeness that we lack. This is a true perception in that we are connected to the bigger world (Props 1:3 and 1:4), and that the bigger world is perfect (see Def. 3:XI) This is a fantasy (a false idea) in that we will never achieve the completeness we crave.

Note: I have used the word ‘hunger’ already in connection with the natural urge to learn. Just as when hungry our eye sees the yellow pasta with the red sauce topped with the yellow cheese and the green flecks of basil and calls this ‘beautiful’, just as our nose takes in the tomato and basil combination and calls this ‘perfect’, so our learning sensibility invests a good teacher or a new theory or body of knowledge as having a completeness or perfection that we lack. He have a hunger for knowledge. We want to learn. This applies to me talking to my supervisor about Nietzsche or Spinoza, to a Year 9 student captured by the adolescent and energetic excitement of Baz Luhrrman’s Romeo and Juliet, to my 22-year-old daughter’s watching of safety videos about motor bike riding now that she has a bike, to my 4-year-old son’s playing with the new set of jungle animals at crèche. We all want to devour these beautiful objects, to incorporate them into our beings.

PROP 23. This perception of the perfection of the ‘non-me’ world is experienced as a desire. We want to possess the object of our desire, which is an aspect of the ‘non-me’ world.

Proof: This is clear from Prop 3:21 immediately preceding, and from the Note.

PROP 24. The organism-learner has an urge to mate with that desired aspect of the non-me world.

Proof: This is just the another way of saying what Prop 3:22 says.

Note: It is as if the masculine part of the learner wants to fertilise the feminine part of the ‘non-me’ aspect with its essence, and the feminine part of the learner wants to be fertilised by the essence of the masculine part of the ‘non-me’ aspect.

PROP 25. The desire will exist until satisfied and a relationship with the ‘non-me’ world has been consummated.

Proof: We have established that the organism is innately expressive (Prop 16) and innately relational (Prop 17), also that it has an in-built urge to increase in power (Prop 2:12) by incorporating aspects of the ‘non-me’ world into itself (Prop 1:7). Given the existence of these natural laws, nothing can bring them to an end except that they be fulfilled. Therefore a desire will exist until satisfied and a relationship with the ‘non-me’ world has been consummated.

Note: Educationists, unlike psychologists, underestimate or do not perceive a number of consequences of the unquenchability of this kind of urge to mate, to be connected, to learn. The urge to mate does not cease to exist if the object of the desire in unavailable; instead, the subject substitutes another object for the desired object which is denied, and attempts to find satisfaction in the substituted object.

This takes a number of forms.

One is the substitution of the mob for the desired but unavailable object. The ignored boy joins the gang and makes his mark on the world through bullying and violence that cannot be ignored. (A consummation has been achieved.)

Another is the substitution of the child’s own body for the mind/body of the desired object, a move may begin with an obsession that the body be perfect and that can lead (after further failures) down the path of self-mutilation and eating disorders.

A third (and I believe quite common one) is the substitution of the organism’s own mind into the desired object. Winnicott suggested that there are people who become so frustrated at repeated failed attempts to establish relationship (firstly with mother, parents, family, friends, clubs, community etc) that they begin to relate to their own minds as if it were an external object. They create solipsistic worlds which they increasingly habitate, cutting themselves off from the messy and painful frustrations of the real world. The relative comfort of these worlds, the fact that they can be controlled or shaped into whatever form the creator desires, makes them a seductive alternative for the complexities and pains of a life lived in society. Managed adequately, this process leads those boys prone to this to write or play music or make computer programs or devise mathematical or scientific ideas, which can lead them back into the world from which they’ve retreated. Badly managed, the process becomes a slippery slope into isolation and perhaps even madness.

Teachers have a tendency, when they see some of these processes being played out in individual students (and we have boys who fit into these categories in all of our classes), to think that here is evidence of the urge to learn, to connect, to animate, to mate, being weak or non-existent, and this undermines our confidence that learning is a natural and inevitable process. What in fact we are seeing, though, is the natural urge continuing to strive to find an outlet, even (in extreme cases) if the outlet turns out to be self-destructive.

PROP 26. The natural urge to learn will always persist; if frustrated it will try to find alternative routes, if thwarted it will persist perversely (even when it damages itself).

Proof: This is to make explicit what is shown in the previous Proposition and Note.

PROP 27. The enhanced organism (an aspect of the non-me world has been incorporated) will now begin to desire another aspect of the ‘non-me’ world. The appetite is insatiable.

Proof: Given the ubiquitous existence of a ‘non-me’ world for all organisms (except for God), there is always more to learn, more to incorporate, more power to be desired.

Note: The appetite is insatiable but not constant. It is always there, but the degree to which it is felt varies. After coitus, for example, it is temporarily stilled. After a big meal, we do not want to eat for a while. There needs to be time for desire to be stir again, for the hunger to return.

Do we allow for this in our classrooms? Is there time for reflection, stillness, rest, or that kind of mucking around with ideas, all of which create a kind of gap or emptiness or vacuum (which can be experienced as a pleasure and/or a pain) into which new ideas or impulses can be drawn? Or are we always in so much of a rush to ‘get on’ and ‘get things covered’ that important stages in the natural processes we’ve been talking about are left out? If so, then the possibilities for true learning are prejudiced.

This tolerance of emptiness, stillness etc should also include a tolerance for experiments or tinkering that might take us down fruitless tracks. We need to develop a classroom culture that not only tolerates mistakes, but also acknowledges their necessity. (All good writers, scientists, sports-stars, musicians, produced their best through a process that included mistakes.) Our preoccupation with making the most of our time, for using every minute wisely, means that mistakes are seen as failures and idle thoughts or stillness as a waste of time. Again good learning is prejudiced.

PROP 28. The attempt to animate others lies at the heart of learning, but can be exploited by a more powerful organism to diminish the power of the desiring organism-learner.

Proof: A successful mating is only possible if each side opens itself up to the other (or, to put it in language consistent with the metaphor used in Parts 1 and 2, if each side adjusts its internal relations to allow for the effect of the other). This means that each becomes vulnerable to the other, though naturally the less powerful organism is more vulnerable than the stronger one, by definition. In some circumstances, then, it is conceivable that the weaker organism will be made still weaker by the powerful organism.

Note: This is obvious in practice, most obvious in the relations between nation-states, but no less true in the relations between students and their teachers or students and their parents.

The student will rightly intuit that he must animate the teacher. He must behave in a way that in some way excites or interests the teacher, so that the teacher will invest energy in the student. In a healthy learning environment, this will happen quite naturally, partly because the teacher is predisposed to be interested in the student, and partly because the student’s learning itself will please the teacher. The teacher, in other words, will be animated by the learning, and this in turn will create the conditions for further learning. (It’s obvious that the teacher’s learning is involved here too, and much might be written about this, but not here.)

But, in an environment where results are more valued than learning (see Part V below), the form of the attempted animation by the student takes on a different form. The teacher allocates the marks (results), there is a confused connection made between getting results and learning, and the student transfers his libido from true learning to the getting of results.

The inevitable consequence of this move is to be tempted to do whatever seems to please the teacher or get the highest marks. If that means (because of the pressure of other curricular and extra-curricula demands) cutting corners in the name of efficiency, then that’s what the student will do. Typical student symptoms of such an unhealthy climate are: regurgitating what the teacher or textbook says, lying about true feelings and real experiences, plagiarising from other students or the Internet, learning how to say nothing impressively, and forgetting what has been learned almost immediately so that, next year, it has to be taught again. Typical teacher symptoms of the same situation are frustration that students won’t think deeply enough, a conviction that some boys are natural lies and cheats, a feeling that their original love of their subject is for some reason being hijacked by administrative overload to do with the calculation of results.

PART 4.Motivation and learning

Preface

Definitions

XIII. Motivation: By this I understand the feeling of desire (experienced in different circumstances as joy, energy, potency, curiosity, love, inadequacy, frustration, anger, determination and hunger) that is both the cause and effect of learning.

Propositions

PROP 29. Learning is its own motivation.

PROP 30. Motivation is caused by perceived need.

PROP 31. Motivation comes from within and without an organism.

PROP 32. Many different emotions or states can cause a student to be motivated.

PROP 33. Motivation is intimately connected with other body/minds.

PROP 34. Students do not have a fixed capacity to learn; their capacity to learn can be developed by teachers.

PROP 35. Our Year 7 changes have as their aim improved conditions for learning..

PART 5.Assessing

Preface

Definitions

XIV. Assessment: By assessment I understand the process used to measure whether learning (as defined above) is taking place.

XV. Outcomes: Outcomes here refers to descriptions of the ways in which a student is more powerful as a result of learning.

XVI. Results: Results are the numerical scores given to students at the end of an agreed period, and are the basis on which grades are given. They have bugger all to do with learning.

Propositions

PROP 36. Assessment is not learning.

PROP 37. Assessment needs to follow teaching.

PROP 38. Assessment is about measuring the amount of learning achieved in a given time span, not about judging/confirming the ‘natural order’ of students.

PROP 39. The results of assessment have as many implications for teachers as for students.

PROP 40. Results and learning are two different things, and are unrelated.

PROP 41. Assessment and the getting of results are two different activities (see definitions).

PROP 42. Our teaching practices are geared to results rather than learning.

PROP 43. Our teaching practice is aimed at producing learning, not results.

PROP 44. The garnering of results focuses on what is common between students, not on what is ‘of their essence’.

PROP 45. A classroom that focuses on results and common standards produces fear, anxiety, lying, cheating and pathological attunement.

PROP 46. To put a numerical mark on a piece of writing is to send a false message about the nature of learning.

PROP 47. Corollary: Because students are learning animals (Axiom 1), they will learn how to get good results, not learn how to learn.

PROP 48. Teaching that focuses on results leads to students who focus on results.

PROP 49. A student who becomes a good learner will get good results, but the opposite is frequently not the case.

PROP 50. When fear or anxiety are greater than the individual’s confidence that he can do something about these by learning, then the learning stops.

ENDNOTES

[1] Indeed the term ‘growing’ is interchangeable here with ‘learning’.

[2] It would mean something if the phrase was ‘learning how to learn better by learning something about learning theory’ … though that wouldn’t be quite as catchy!

[3] Note about Stern’s researches.

[4] Another aspect of the body/mind is that its consciousness or knowledge can reside in different places in the organism, in the mind consciously or in the body unconsciously. We can know something without knowing that we know it, and can be alerted to the existence of this knowledge through a bodily symptom (we shift in our seat because our body knows that we are bored), a spontaneous impulse (a Year 9 student in one of my classes was shocked when, in a silent gap while I was struggling to articulate something, suddenly shouted: ‘Just say it!’, indicating a frustration his conscious mind couldn’t calmly articulate), or a dream.

Mary Macken-Horarik sent me the following via email:

Hi Steve,

This is a fascinating excursion into the mind and heart and rigorous thinking of Spinoza and of what happened in your own thinking as a result of the collaboration with him. But I found myself wondering at the end of the excursion where it landed you in terms of teaching. Did it galvanize you or make you feel yourself to be on solid ground when you did teach? Please write some more about this if you can find the time and have the interest to do so.

Mary

I won’t say why, but with this article on Spinoza in mind, you might enjoy the book, “The Weight of Ink” by Rachel Kaddish.

Cordially,

J. D. Wilson, Jr.