A love towards a thing eternal: Spinoza and the classroom

Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 2014 Volume 43, Number 5, November 2015

A love towards a thing eternal: Spinoza and the classroom

Steve Shann, Michele Bauer, Rachel Cunneen, Jaki Troy and Courtney Van Blerk

Abstract

There is a growing concern about the struggles of early career teachers and an understandable questioning of the preparation being offered by teacher education courses. Are our preservice teachers being given workable strategies and techniques to allow them to survive the early years? Is it strategies and techniques that are primarily at issue here? Could it be that there is something more fundamental, to do with an underlying philosophical understanding about human nature, the desire to learn and the need to relate? I want to suggest that instruction about strategies and techniques is too often built on an insecure and incompatible foundation of assumptions about the nature of the world of sentient beings and their relationships. Ontology matters. Philosopher Spinoza divided the world of thought into ideas that were adequate – contributing to our well-being, potency and happiness – and those that were inadequate – leading us to feel weak, at the mercy of outside forces, and sad. I want to argue, with Spinoza, that inadequate ontologies lead to a sense of impotence and frustration, and that adequate ideas – a stronger ontology – can underpin and sustain a more durable pedagogy. I explore this idea by looking at some classroom events through a Spinozean lens.

1.

And the rain fell, and the floods came, and the winds blew and slammed against that house; and yet it did not fall, for it had been founded on the rock. Everyone who hears these words of mine and does not act on them, will be like a foolish man who built his house on the sand. The rain fell, and the floods came, and the winds blew and slammed against that house; and it fell – and great was its fall.

The Gospel according to St Matthew 7:25–27

It seems that there is something of a storm raging in education (Clandinin, Downey, & Huber, 2009, p. 142) and it is now beyond dispute, and of increasing concern, that there are casualties amongst early career teachers (Fauk, 2010, p. 95; Johnson et al., 2012). Could it be that some of our work on early career teacher capacity is built on sand? Are we ignoring some potential rockier sites? I want to argue in this paper that the answer to both these questions could well be “yes”.

There is a great deal of building activity though, that is for sure. In particular, there is feverish activity going on in university teacher education courses and in school-mentoring programmes (supported by the roll out of the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers) to explicitly teach our beginning teachers the strategies and techniques that will equip them to operate effectively in increasingly complex and challenging classroom environments. We have teacher education programmes and school-based mentoring schemes in place to support beginning teachers as they (to draw on the language of the AITSL, Australian Professional Standards for Teachers)

understand how students learn,

discover content and teaching strategies for full participation,

employ literacy and numeracy strategies,

structure and sequence learning programmes,

use effective classroom communication,

manage classroom activities and challenging behaviour,

assess and report in timely and appropriate ways, and

engage in professional learning to improve practice.

Professor Raewyn Connell (2009), however, warns us that this (implicit and often explicit) emphasis on strategies and techniques might be dangerous sand. In an article called “Good teachers on dangerous ground”, she suggests that in recent years there has been a shift away from what she calls a “humanist” approach to teacher education which “rested on certain foundational areas: history of education, philosophy of education, educational psychology and sociology of education” (p. 216), and towards a “technical vision of the good teacher” (p. 217). This is a view of teaching as a learned collection of “specific, auditable competencies and performances” (p. 220). The audit culture in education, she says,

. . . construes teachers as technicians, enacting pre-defined “best practice” with a pre-defined curriculum measured against external tests – a situation for which skill, but not intelligence, is required. (p. 224)

It is a view that rests on the (unstable) notion that teaching is a quasi-science, where possession of the appropriate tool kit (knowledge, skills, strategies) can lead to predictable and desirable outcomes. And, as Warren Liew (2013) argues, there is no evidence to suggest that this is the case. Indeed, he suggests, central to what we know about teaching is that it is a performative act, inevitably involving live bodies and symbolic forms, where “a teacher’s actions and decisions are infinitely susceptible to revision and reinterpretation in the midst of real-time interactions” (p. 263).

Practically limitless in number and kind, these multiple variables participate in countless simultaneous and multidirectional interactions best characterized as volatile, indeterminate, and contingent. (p. 270)

Perhaps, then, given the inevitable uncertainties that science increasingly insists on, there is no rock on which to build a more secure foundation.

2.

The Seventeenth century philosopher, Spinoza, asked himself the same question.

After experience had taught me that all the usual surroundings of social life are vain and futile; seeing that none of the objects of my fears contained in themselves anything either good or bad, except in so far as the mind is affected by them, I finally resolved to inquire whether there might be some real good having power to communicate itself, which would affect the mind singly, to the exclusion of all else: whether, in fact, there might be anything of which the discovery and attainment would enable me to enjoy continuous, supreme, and unending happiness. (Spinoza, 1677a, p. 3)

Spinoza claimed to have found such a thing.

But love towards a thing eternal and infinite feeds the mind wholly with joy, and is itself unmingled with any sadness, wherefore it is greatly to be desired and sought for with all our strength. (Spinoza, 1677a, p. 5)

That is a big call, and one that might sound discordant to a twenty-first century ear attuned to notions of uncertainty, complexity and the indeterminate.

Is it possible, though, that Spinoza’s philosophy might provide some useful alternative to the quasi-scientific “strategies and techniques” approach? Is there something in this “love towards a thing eternal” that might form a less shifting foundation for beginning teachers’ classroom practice?

What might we learn, in other words, by looking at what transpires in a classroom through a Spinozean lens? This is what we attempt to do in this paper.

3.

Before I do so, however, I want to place this move within a growing educational interest in the lifeworld of classrooms seen through a Spinozean lens. This lens focuses our attention on the enlivening energies and couplings driven by the human desire to become. We are animated, said Spinoza, by our drive to preserve our being, “a telos or vocation that is immanent in the nature of every human qua human” (Aloni, 2008, pp. 535–536). This drive is experienced in our body-minds, and “involves treating thinking in terms of an embodied process, making it inherently entangled in the material relations that the individual body is engaged in” (Dahlbeck, 2011, p. 13). It is, says Semetsky (2010), “an objective capacity to affect and be affected that makes us think and learn” (p. 478). Through this lens, we see teachers and students “as made up of forces connecting with other forces” (Mercieca, 2011, p. 1), “at once social and desiring” (Deleuze, as quoted in Semetsky & Depech-Ramey, 2010, p. 1).

The moments, “where actual relations between actual bodies – of children and pedagogues alike – are treated as the starting point for understanding the larger social body that they are part of” (Dahlbeck, 2011, p. 2) are affect-laden, fluid, relational and unpredictable. They are, in their early stages, necessarily tentative, playful and uncertain, attended typically with uncomfortable feelings of perhaps-not-belonging, of feeling concerned that the yearning to be included may not be realised. Things are fluid, “in perpetual movement; a moment is formed by the specific, particular relationship among forces that will change in any number of possible ways” (Semetsky, 2010, p. 480). The doubts and uncertainties are inevitably felt by the teacher as well as the student. The teacher’s uncertainty and his/her inevitable lack of control over the emerging and shifting field, contributes to a developing tension which threatens the efficacy of the learning and at the same time gives it a potential life which the participants can share and make something of. Learning begins in uncertainty, in the opening up of gaps and unknowns (Shann, 2010).

This is a dangerous and exciting business, failure always a vitalising possibility. “Becoming by definition is an experiment with what is new, that is, coming into being, be-coming” (Semetsky, 2010, p. 480).

The teacher’s role, then, is to concern him/herself with what is present, with the “moments that are formed by the relation of forces present” (Tocci, 2010, p. 769), with the “singular flows of power pulsating with a given intensity and always interacting with and affecting other, external, powers in its constant endeavor to persevere” (Dahlbeck, 2011, pp. 3–4), rather than with “goals and purposes based on external relations from a view- point that can only be described as being situated somewhere beyond existence itself” (Dahlbeck, 2011, pp. 4–5).

4.

Spinoza himself had a perplexing “reluctance – conscious or unconscious – to deal with educational topics in his writing” (Aloni, 2008, p. 531). How, then, might we further mine his more general philosophy for its educational implications? How might we adapt his philosophy to an educational setting? How might we imagine what he would have said about specific classroom events?

The approach I have taken in the rest of this paper is as follows.

First of all, in Section 5, I have drawn on his Ethics (Spinoza, 1677b), and letters (Spinoza, 1677a), along with some of the commentaries referred to in the previous section, to help me imagine what Spinoza might have said had he written explicitly about education. I have written this in the form of a letter from Spinoza to his friend, Henry Oldenburg, a letter composed of the kinds of propositions, definitions and proofs upon which his Ethics is built. Then, in Section 6, I have written a reply to Spinoza, outlining how his ideas about “a thing eternal and infinite” throw light on specific events in a university class in 2009, and then in a single lesson taught by an early career secondary English teacher in 2011.

5.

To the very noble and learned Mr Henry Oldenburg, Most noble sir,

I thank you and the very noble Mr. Boyle very much for kindly encouraging me to go on with my Philosophy. I do indeed proceed with it, as far as my slender powers will allow, not doubting meanwhile of your help and goodwill.

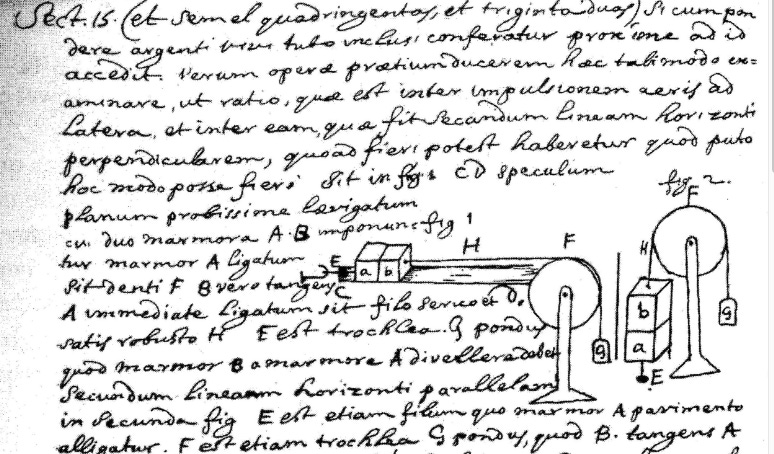

I am presently engaged in writing about the application of my Philosophy to the education of the young. I have begun to articulate a series of Definitions and Propositions, to which I will attempt to attach Proofs, in a book to be called ‘On the natural laws of learning’. Here are the Propositions I will lay before my reader, should the book ever find its way into the public space:

Part 1: Learning as belonging to nature

Definitions

Learner: I define learner here as any person engaged in the business of learning (see definition below).

Learning: I understand by learning a natural process by which the learner or organism, through the engagement of his body/mind with other body/minds, becomes more what he essentially (or potentially) is. Learning, then, is to do with expressing the essence and enhancing the power of the learner.

Natural: I do not use the word ‘natural’ to mean either ‘easy’ or ‘happens by itself without interference or the involvement by others’. Instead I use the word in a more biological or environmental sense, to mean ‘being a part of the natural world’. Learning is the result of an inbuilt natural tendency or urge in the organism to attempt to increase in its own being or essence or power. Learning, then, is natural for a student in the same way that growing is natural for a plant. Indeed the term ‘growing’ is interchangeable here with ‘learning’.

Propositions

I. Learning belongs to nature.

II. A learner-organism has an inbuilt urge or necessity to exist.

III. An organism is always a part of another organism.

IV. Nature is always a highly complex and dynamic set of inter-relationships.

V. The learner naturally develops the capacity to adapt.

VI. The inbuilt urge necessarily involves others.

VII. The impulse to learn is to attempt to know better (to feel more deeply) the connection between the learner and the world beyond the learner.

Part 2: Learning as an activity directed towards power

Definitions

Body/Mind: By this I’m drawing attention to ‘two sides of the one coin’, where often (and misleadingly) we think about the body/mind as if it were two separate things. A learner is an individual with a body/mind. This body/mind can be seen in two different ways: the learner can be perceived as a body which has ideas, and it can be seen as a mind which expresses itself bodily.

Power: By power, I mean the individual’s capacity to be active, to be effective, to create effects and affects, to be an agent. The opposite is to be passive (or powerless).

Propositions

VIII. To learn is to act.

IX. To act is to have an effect.

X. To learn is to have an effect.

XI. To learn is to become more powerful.

XII. To learn is to become more developed in what one already is. The learner’s essence is enhanced.

XIII. There always exists a connection between the learner’s essence and his learning.

XIV.This connection between learning and essence exists in the learner’s body/mind

XV. Learning changes the world (of the organism and of the bigger world to which it is connected). This changed world requires new adaptations from the learning. Learning, therefore, is never-ending.

Part 3: Learning as an activity directed towards mating and animating

Definitions

Intelligence: I understand by intelligence the capacity of the individual to employ his essential faculties in order to become more powerful.

Pleasure: By pleasure I mean the emotion experienced from having our impulses gratified.

Pain: By pain I mean the emotion experienced from having impulses frustrated.

Perfect: By perfect, I mean complete in itself without the need of anything extra. In this sense the only thing that is perfect the totality of all that exists – God or Nature. Every other organism belongs to another organism (Prop III), and is incomplete – imperfect – without it.

Propositions

XVI. Learning involves activity. It is never a passive process, but always excites or animates.

XVII. The organism-learner is innately relational, ie it has a natural tendency to form relationships with other organism-learners.

XVIII. The organism-learner is innately expressive.

XIX. Learning always involves the emotions. Pain and pleasure are inevitably involved.

XX. These pains and pleasures are experienced by both aspects of the body/mind.

XXI. The mind/body of the organism perceives aspects of the not-me world as having a relative perfection or completeness it lacks.

XXII. This perception of the relative perfection of the not-me world is experienced as a desire. We want to possess the object of our desire, which is an aspect of the not-me world.

XXIII. The organism-learner has an urge to mate with that desired aspect of the not-me world.

XXIV. The desire will exist until satisfied and a relationship with the not-me world has been consummated.

XXV. The natural urge to learn will always persist; if frustrated, it will try to find alternative routes, if thwarted it will persist perversely (even when it damages itself).

XXVI. The enhanced organism (an aspect of the not-me world has been incorporated) will now begin to desire another aspect of the not-me world. The appetite is insatiable.

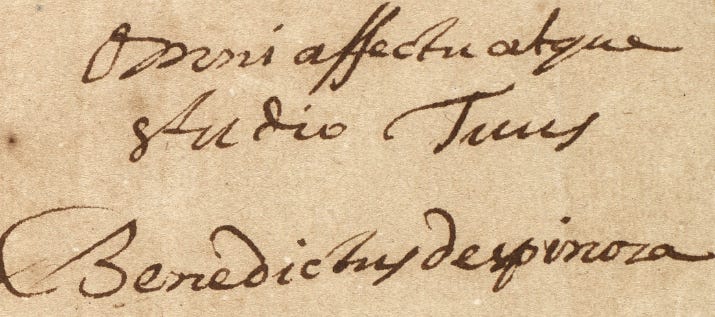

I wrote this letter last week. But I could not send it because the wind prevented my going to the Hague. That is the disadvantage of living in the country. Therefore when you see that I do not answer you as promptly as I should, you must not think that this is due to my forgetting you. Meanwhile time urges me to bring this to an end. Of the rest on another occasion. Now I can say no more than to ask you to give a hearty greeting from me to the very Noble Mr. Boyle, and to remember me who am

In all affection yours

B. de SPINOZA

Voorburg, 20 November 1665

6.

To the very noble and learned Mr Benedict de Spinoza, Most noble sir,

What a shame you will never receive this letter, or know how much joy the discovery of your lost letter to your friend, Henry Oldenburg, has given me. What you write about ‘the natural laws of learning’ seems, to me, of special importance to my 21st century world, where our understanding of the true nature of learning has become undermined by inadequate ideas. In particular, and in spite of our constructivist rhetoric, we continue to be guided by the assumption that our students are incomplete minds in need of external instruction. You remind us that, on the contrary, a student is innately relational and expressive, driven by both a desire to persevere in its own being and to mate with the not- me world in order to enhance its essence. Your ontology, it seems to me, provides us with a firm foundation without which our customary pedagogic approaches can easily totter.

When we discipline ourselves to see the world through the prism of your Twenty-six Propositions, we begin to see aspects of learners and learning that are otherwise invisible. We see more deeply and more adequately. Seeing the classroom through the lens you have provided for us provides us with the philosophical grounding that makes our pedagogy more durable.

I want to show rather than assert here. I want to describe to you an intellectual encounter involving three students with whom I worked a few years ago. It is, I think, a story which, when viewed through the lens you have made available to us, makes visible in the real world many of your abstract Twenty Six Propositions.

7.

I was teaching a university teacher education unit called ‘Literacy across the secondary disciplines’, and Michele, Jaki and Rachel were three of my ninety Graduate Diploma in Secondary Education students. As part of our work together, I asked the students to wrestle with what I hoped would be an unsettling and fertile question: ‘Redefining writing? What next! Is this just a distraction from our core disciplinary business?’

The resulting discussion about literacy was interesting in itself, but this is not why I want to tell you this story. Instead, what I experienced, observed and documented with those three students was, it seems to me, both consistent with, and illuminated by, your Twenty-six Propositions. We four – teacher and students – were animated by feelings of potency and joy, not because everything was simple and smooth (it most certainly wasn’t!), but because our learning was located in, and generated by, our body-minds engaged in something deeply natural. We were living out what you have described; we were body/minds deeply aware of the connection between our individual desires to know more and to feel more potent on the one hand, and our relationships with each other on the other.

At various times during this encounter, these three students and I were confused, indignant, anxious, uncomfortable, surprised, absorbed, intrigued, opened-up, impatient, stirred, pressured, ambivalent, excited, yearning, dizzied, frustrated, encouraged, connected and elated. We were, to use the language of your Twenty-Six Propositions, active body-minds animated by an inbuilt urge to exist, express, adapt and affect. Pain and pleasure were inevitably involved as we attempted to take in what we experienced as a gap in our own imperfect understanding of things.

We began, as I said, by wrestling with an unsettling question. Some of the other students in this class were clearly unhappy about this. Nature, as you said in Proposition IV, is always a highly complex and dynamic set of inter-relationships. One student complained that ‘redefining writing in a vague way . . . effectively makes writing equal to any communication devalues writing as a skill’. Another wrote that he was ‘having a little difficulty finding any relevance to the lofty discussions that are occurring here in this unit’. But then, a third student, William, responded to some of this discontent by writing an extended piece called ‘Writing as continuum’, a piece which was soon to become (as I will show) the focal point of the body-mind encounters between Michele, Jaki and Rachel.

William argued that images, creative writing, artistic works and scientific writing all expressed and communicated ideas and meanings, and that they all existed on a kind of historical continuum, stretching back to cave painting and then hieroglyphics, through the printing and industrial ages where the written word was privileged, and now into a post- industrial society with a re-emergence of the use of images through new technologies.

William’s elegant post (I have not done it justice here) provoked a spirited discussion.

Michele, for example, had been thinking about ideas like William’s for years, but always alone, wondering if others saw things as she was beginning to, wondering how her natural inclination to take a big-picture approach was going to work once she got into her own history classes and felt the pressure of small-picture syllabi. She wanted her students to grasp big changes, as she’d been stimulated to do all her adult life. But, until she read William’s post, this had felt like a project to be pursued on her own, in her own quiet way, through reading and thinking. William’s post signaled to Michele that she wasn’t the only body/mind on this course wanting to think more broadly. An organism, you remind us, is always a part of other organisms (as with your Proposition III), and the inbuilt urge necessary involves others (VI). The impulse to learn is an attempt to know better (or feel more deeply) the connection between me and the not-me world (VII).

Michele began to imagine a potential dialogue here; even bigger conversations, if others were interested. Maybe some of her fellow students would like to know about the things she had been reading? Soon after William had posted his piece, Michele went online and typed:

Hey William,

I am with you on this one. I think writing, and literacy in general, need to be unlocked from‘Western’ boundaries. I am reading some articles that support this. Let us break out writing from the constraints it has been given!!!

I think our non-linear, multi-modal world has found a way to bring all worlds together, but it is not going to be by sticking to our traditional ‘reading and writing’ literacy methods.

Michele

A second student, Jaki, was also wrestling with the question about the nature of literacy. Two distinct intellectual strands in her thinking – the way she’d always used words on paper to represent her thoughts on the one hand, and her love of images as she trained to be a visual arts teacher on the other – were being conflated in this discussion, and it was surprisingly unsettling for her.

But, as you say in your fifth Proposition, the learner naturally develops the capacity to adapt, and Jaki’s was an agitation that stimulated her desire to engage, her ‘urge to mate with [a] desired aspect of the not-me world’ (XXII). As Jaki herself put it, she wanted to explore a field ‘without hermetically sealing it off’.

This meant playing with ideas, letting thoughts emerge spontaneously, and communicating these emerging thoughts with others in the group. After reading William’s post, she wrote online:

Hi, everyone on this blog so far. You really started something here William! What I can really appreciate is that I am not alone, I was concerned that I was going too far out on a limb in the way I was thinking about this. What I can see so clearly now is that this collaboration is really working for me, it is supportive, provocative and leading me towards a larger expressive exercise. It is great to read how everyone is thinking creatively about human (and other) expression.

I am coming to a view that writing is indistinguishable from the whole range of human experience and creative endeavour. A metaphysical light is shining on my understanding of writing. An almost limitless concept of writing is emerging for me, that it is anything which conveys meaning. That reading and writing and creating are all inextricably bound together and are not just human constructs. It is all written all around us and we read into everything what we want and desire to know.

Here was Jaki experiencing the not-me world as having a relative completeness that she was reaching out to incorporate. Here was a part of Jaki ‘desiring and seeking and longing for some other part that holds tantalizing hopes of filling the holes that perforate any seeming semblance of wholeness’.

Three hours later, a third student, Rachel, responded online:

Jaki – wow. This has given me so much to think about. I really like this. I’m an English and ESL teacher – and find that I’m beginning to use dance, art and song to convey ideas – particularly for those who struggle with conventional forms of reading and writing. It seems to me that the old parameters are breaking down at the moment. It’s often scary but exciting too. Some of the parameters that challenging me most are the ones that you articulate so beautifully – so thank you.

This discussion was affecting Rachel for reasons particular to her; there was a connection between what had always mattered deeply to her and what she now wanted to learn more about (Proposition XIII). For some time she had been politically concerned about ecological issues and, stirred by some of the writings of Val Plumwood (2008), had a particular interest in the ways our society kept favouring and elevating the lives and expressions of human beings over the non-human world. At the same time, as a writer she harboured a hope that words held some kind of key to a possible way out of environmental catastrophe. For some time now, she’d been thinking about a concept that might be called ‘eco-literacy’, and this university collaboration felt like an opportunity to grapple further with this.

Both pain and pleasure are inevitably involved in this kind of learning (XIX). Rachel read, in our online space, the rumblings from some of the students in the course. These posts touched a sore spot in her: the worry that her love of literature was a personal indulgence, an escape from reality. She wondered if maybe she had been responsible for this outburst of concern, as she’d written in an online post just a couple of days before:

I’m struggling to wrap up my own report for tonight. I’m finding it much harder than expected – for me it’s difficult to extend a meditation on writing into more practical ideas about pedagogy. Anyone else the same?

But Rachel was not satisfied with this. She wanted to find her way to a deeper, more satisfying response. She waited until her young daughters were asleep, poured herself a glass of wine, and wrote, in one sitting, a story that had been percolating all through these discussions with William, Michele, Jaki and others. The story began:

I sit outside, wishing for silence. It’s a clear night and I see the pale glow of a computer screen in the house next door. So many people ‘talking’ to each other as they spill their thoughts onto and into their own little networks. Sometimes it’s as if a thin mist of chatter hangs in the night sky, over the steaming planet.

Rachel then wrote about two students, Deng, a refugee, and Tassie, born and raised in affluent Canberra. One of the themes of her story was the power of words, the issue that she’d been exploring all the way through our unit and in her online discussions with Jaki and Michele. She finished her story with this:

Deng began [as a young child] by drawing stick figures in the sand, Tassie began by copying her name from her preschool teacher’s example – but both were learning to leave their mark on the world. In doing so they change it, little by little. Or so I believe and so I keep teaching as if I know I am changing the world for the better. I keep quiet about my convictions while we are learning to put spaces between each word (Deng) or to use apostrophes correctly (Tassie – again and again) but my intent is there, in every tap of the keyboard, every scratch of the pen.

By the end of our semester, Michele, Jaki and Rachel, largely through their connections with each other (XVI), had a sense of having possessed a desired aspect of the not- me world (XXI).

Most noble sir, do I strain your Propositions by attempting to link them so explicitly with what happened in my classroom? Am I pushing things too much in suggesting that your philosophy directs our attention to what exists at the heart of learning, and therefore provides us with a practical guide for teachers, and one which leads to teacher and students feeling more joyful and potent? I think not.

With deep respect and heartfelt thanks, I remain yours

Steve

Canberra, October, 2013.

8.

Michele, Jaki and Rachel were exceptionally articulate and engaged students, and we might wonder if the same underlying Spinozan dynamics are evident in a more typical secondary classroom. Does a desire for a perceived lack play such a powerful role there? Do we find, in a Year 10 English class in a typical neighbourhood government high school, for example, the same purposeful urge to relate intellectually with others in order to possess more of the not-me world?

Earlier this year, Courtney (in her second year of teaching) told the following story to me and my current teacher education students.

I had a crazy lesson today in a Year 10 English class. 20 students. Week 2 of the new year. The type of class list that every teacher looks at and pats you on the shoulder with a look of pity in their eyes and says “good luck”. Last period of the day. Our topic was Prejudice.

I gave the students an “expectations” talk to start the lesson. I started to give instructions and several students began to talk over the top of me. I used all of my usual techniques waiting, reminders to settle, looks, proximity control . . . nothing was working. I handed out the first activity. As I helped three students work through one of the questions, a fight exploded on the other side of the class. I turned to see a very angry teenage girl screaming and swearing, while another ran out of the class and several other students laughed. I sent the girl with the temper outside to cool down. I turned to the class and told them that I expected to see question 1 complete by the time I got back.

I stepped through the classroom door. Another teacher was standing outside and offered to follow the girl who had taken off. I turned to Little Miss Temper. She had given me attitude all week. She was sitting on the ground with her arms crossed.

Let us pause here for a moment, and contemplate the scene: a young teacher wanting to introduce an important topic – prejudice – to her class, but seeing her carefully prepared lesson being undermined by a disengaged Year 10 class and two girls embroiled in an out- of-control spat.

This is the moment when what a teacher believes about human nature really matters.

If Courtney, deep down, had thought that these kids did not want to learn, or did not have the capacity to engage, or that they were obsessed with their social worlds to the exclusion of all else, then everything that had happened up to this point in the lesson would confirm her underlying ontology. Her strategies and techniques would then evaporate, and she would find herself falling back on a kind of carrot-and-sticks approach that would sap her energy, drain her spirit, and contribute to a growing sense in her that she was wasting her considerable intelligence and creativity as a teacher. This, I am suggesting, is the experience of many of the young teachers who end up leaving the profession after countless days of apparently fruitless struggle and stress.

If, on the other hand, Courtney believed that her students were, superficial appearances to the contrary, learner-organisms with an inbuilt and unquenchable desire to adapt, relate and become more powerful by incorporating more of the not-me world into their own gapped experience of things, then she would persist with her constructivist approach, confident that she and her students would find a way through in the end, fraught and uneven though the progress might be.

Let us see what actually happened.

I sat down on the ground in front of her and just asked, as genuinely and respectfully as I could, “What just went on in there?”. She calmed down, opened up and accepted responsibility.

I still had a class resembling wild monkeys. I was quickly sorting through strategies in my head. What would they respond to? How to get their attention? How to start building relationships? I tried to bring the class back into a conversation about prejudice. Some were having troubles with getting examples. Six students continued to chat while I tried to talk.

Then I decided to fight fire with fire. In the biggest voice I could muster I began: “For goodness sake! Teenagers are so rude! You all lack respect! You are self-centred, self-absorbed, sex-crazed, risk taking and immature.”

As my momentum built, the class began to fall silent. By the end of the rant, they were all looking at me. Wide eyed and engaged. “But what about teachers, miss?!?”I pulled out a pile of post-it notes. I wrote my rant on the first post-it and while I had their attention, I stuck it to the wall.

“Okay, pretend that this class is all on Facebook. I just put this post up. I would like you all to ”comment“ on my post.” They all fervently began to write responses and stick them up.

I had been trying to get this class to have discussions about prejudice. I decided that using a language/text that they use daily (Facebook) might be the key to getting them to have a discussion. While they wrote stereotypes about teachers and disagreed with my first ranting post, I wrote three discussion points on post-its and labelled them as “status updates”.

I got their attention again and told them to now read each status update and respond to one. As the momentum built, they began to respond to each other’s comments. They asked if they could “like” comments as well and I allowed it.

They were now paying attention to each other’s opinions, and encouraging each other in voicing these opinions. Students who had not said “boo” for a week and a half were freely writing paragraphs about prejudice.

As the lesson drew to a close, I pulled down the posts in response to my rant. I read each response out loud. “Teachers do not care”, “Teachers do not like teenagers”, “Teachers do not listen to all sides of a story”, “Teachers exaggerate”, “Teachers say we do not work hard”. I added in that we eat children for fun.

I joked my way through the comments. As I got to the end, one of the boys with a lot of attitude said “Miss, you know we are not talking about you.”

“But you hardly know me,” I replied.

That is when Little Miss Temper said, “But Miss, you are the first teacher to ask me what happened in a fight. They usually just kick me out and give me detention because I have a temper.”

Another boy chimed in “Hey Miss, this was an awesome lesson.” I sent them out on the bell and did a little happy dance.

9.

Courtney herself attributes her success on that day to her ability to apply particular constructivist pedagogies of Piaget, Bruner and Dewey: learning needs to be built on prior knowledge and real interests, meaning is co-created through collaborative engagement.

But I think it goes deeper than that.

Courtney was not deterred by appearances. She knew that beneath the apparent antagonisms, resistances and ennui, her students had a desire to know, to be connected, to adapt and to learn. Her students wanted to fill gaps; she just needed to find a way to make that possible. Her underlying ontology supported her strong grasp of pedagogical possibilities by convincing her that what she saw in those first few minutes of the lesson – the inattentive pupils, the explosive fight – was only part of the reality that confronted her, and that perseverance, firmness and a belief in the capacity and willingness of the students to learn would, in the end, get her somewhere.

A toolkit of strategies and teaching techniques is not enough.

This raises significant questions for teacher education. In an era where the economic drivers are increasingly pushing us online, where are the relational spaces where deeper questions can be explored? Where, in the modern university, are the equivalent of Courtney’s classroom? In an era where the utilitarian (“Give me techniques that work, not ideas that distract!”) is often valued at the expense of the philosophical, where are the university units that encourage young teachers to examine and test the efficacy of their assumptions about human nature?

Inadequate ideas limit our actions; a strong and grounded philosophy makes us more potent. A confident grasp of a sustainable and true underlying ontology creates confidence, courage and at least a hint of Spinoza’s “thing eternal and infinite [which] feeds the mind wholly with joy”.

References

Aloni, N. (2008). Spinoza as educator: From eudaimonistic ethics to an empowering and liberating pedagogy. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 40(4), 531–544. doi:10.1111/j.1469-5812.2007. 00361.x

Clandinin, D. J., Downey, C. A., & Huber, J. (2009). Attending to changing landscapes: Shaping the interwoven identities of teachers and teacher educators†. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 37(2), 141–154. doi:10.1080/13598660902806316

Connell, R. (2009). Good teachers on dangerous ground: Towards a new view of teacher quality and professionalism. Critical Studies in Education, 50(3), 213–229. doi:10.1080/1750848090 2998421

Dahlbeck, J. (2011). Towards a pure ontology: Children’s bodies and morality. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 46(1), 8–23.

Fauk, T. (2010). Literacy as dialogue. Philosophical Studies in Education, 41, 72–82.

Johnson, B., Down, B., Le Cornu, R., Peters, J., Sullivan, A., Pearce, J., & Hunter, J. (2012). Early career teachers: Stories of resilience. Adelaide: University of South Australia.

Liew, W. M. (2013). Effects beyond effectiveness: Teaching as a performative act. Curriculum Inquiry, 43(2), 261–288. doi:10.1111/curi.12012

Mercieca, D. (2011). Becoming-teachers: Desiring students. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 44, 43–56.

Plumwood, V. (2008). Shadow places and the politics of dwelling. Australian Humanities Review, 44(March), 1–9.

Semetsky, I. (2010). The folds of experience, or: Constructing the pedagogy of values. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 42(4), 476–488. doi:10.1111/j.1469-5812.2008.00486.x

Semetsky, I., & Depech-Ramey, J. A. (2010). Jung’s psychology and deleuze’s philosophy: The unconscious in learning. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 44(1), 69–81.

Shann, S. (2010). Agitations and animations. English in Australia, 45(3), 65–74.

Spinoza, B. (1677a). On the improvement of the understanding (R. H. M. Elwes, Trans.). New York, NY: Dover Books.

Spinoza, B. (1677b). The ethics. London: Everyman.

Tocci, C. (2010). An immanent machine: Reconsidering grades, historical and present. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 42(7), 762–778. doi:10.1111/j.1469-5812.2008.00440.x