1.

One of my grandchildren in Melbourne has been unhappy at school. Her parents have been looking at alternatives, and last week I travelled down to Melbourne to visit, with my granddaughter and her parents, Preshil School.

We spent a morning there with other interested parents and students, listening to the new Principal and the Primary School Co-ordinator, touring the primary school campus, and hearing from four of the students.

It was an exciting visit for me, bringing back happy memories from 44 years ago. I spent three days at Preshil in 1980, sent by my alternative school (the AME School in Canberra) to shadow its famous and distinguished Principal, Margaret Lyttle, and to see what we might learn from its philosophy and practice.

When I got back to Canberra from that visit in 1980, I wrote a report for the AME staff, which I’ve reproduced elsewhere in The Mythopoetic Classroom.

2.

What was it about last week’s visit that I found so exciting?

The most obvious answer is that the school seemed a possible solution for my granddaughter. She would go into a small class of about 14 in a sun-filled classroom set amongst the trees. I stood on the balcony outside the classroom and watched the class in action.

At first the children were gathered around the teacher, planning the day perhaps, or sharing a story. Then the group dispersed. A small group stayed with the teacher, another group of four moved to a table and began working on some task, and one student went by herself to a corner of the room and started reading. There was a sense of each child finding his or her own way into the day’s learning.

I could imagine my granddaughter being at home in that space.

3.

There was an adult in our group who found all the talk about creativity and student autonomy less convincing than I did. I heard him say something about the principal’s educational jargon; he’d heard it all before, in a number of schools, where the rhetoric had proved to be far from the reality.

I didn’t see it in the same way.

I’ve always been excited about the possibility of what we used to call progressive education. I read A.S. Neill’s Summerhill while I was at university and found the existence of that school thrilling. I worked for a year at a school in Aberdeen, co-incidentally called Summerhill Academy, whose headmaster was a friend of A.S. Neill. I taught at the progressive AME School for eight years; it was also the school my daughters attended.

Why does the Preshil’s principal’s talk stir these old enthusiasms? Why does what I see in that environment give me so much pleasure?

‘The eye and the wound are one and the same’, said James Hillman in his book The Dream and the Underworld.

What is the wound that determines what I see?

Who knows!

But the question revives a memory.

4.

I am nine years old, alone in the living room at home. I have a favourite piece of music, one of my father’s record collection. It is Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2, and it sits now in the record player. I draw the curtains, turn off the lights, then rearrange all the living room furniture so that, in my imagination, I am standing on the edge of a huge and mysterious forest. The chairs are the trunks of trees, and the paths between the trees are little inviting openings to the dark unknown beyond.

The room rearranged and dark, I turn on the record player and carefully place the needle at the beginning of the first track.

The first gentle piano chord is heard, and I imagine myself standing at the forest’s edge. More piano chords, building now in intensity, and as I wriggle through a gap and into the forest, I feel my heart beating and my young soul soaring. The violins come in over the continuing thrum of the piano, and I’m suddenly standing between the trees, the wind blowing through the leaves and onto my face. I begin to sway, and then, as a much gentler and more lyrical theme is introduced, I begin to walk slowly around the furniture, imagining that I’m now in the heart of the forest, surrounded by huge trees and thick undergrowth. There’s another shift in the music’s mood, a crescendo, and I’m suddenly skipping and twirling around the darkened room, dancing, leaping onto furniture, feeling light and energetic and graceful.

And then, with the part of me still in the real world of the family living room, I hear my mother’s car pull up in the carport. I’m convinced that my mother is going to hear the music and see me dancing, and she’ll be so happy.

I hear the front door open. I sense my mother standing, watching. I shut my eyes as I now move slowly to a lyrical phrase.

The music suddenly stops.

I open my eyes.

My mother has turned on the lights and is standing by the now-silent record player, hands on hips.

‘What on earth, Steve! Who do you imagine is going to clean up this mess?’

I’m shocked. Incredulous. Speechless.

Perhaps I clean up the room. Perhaps I just run away to my bedroom. I don’t remember that bit.

This memory of mine, this wound that I felt, is not the literal determinant of what I would then search for in my professional life. But incidents like this one, and many others like it when, the following year, I was sent to boarding school, had me searching, even while still at school, for ways in which the creative spirit might find a home in a classroom.

5.

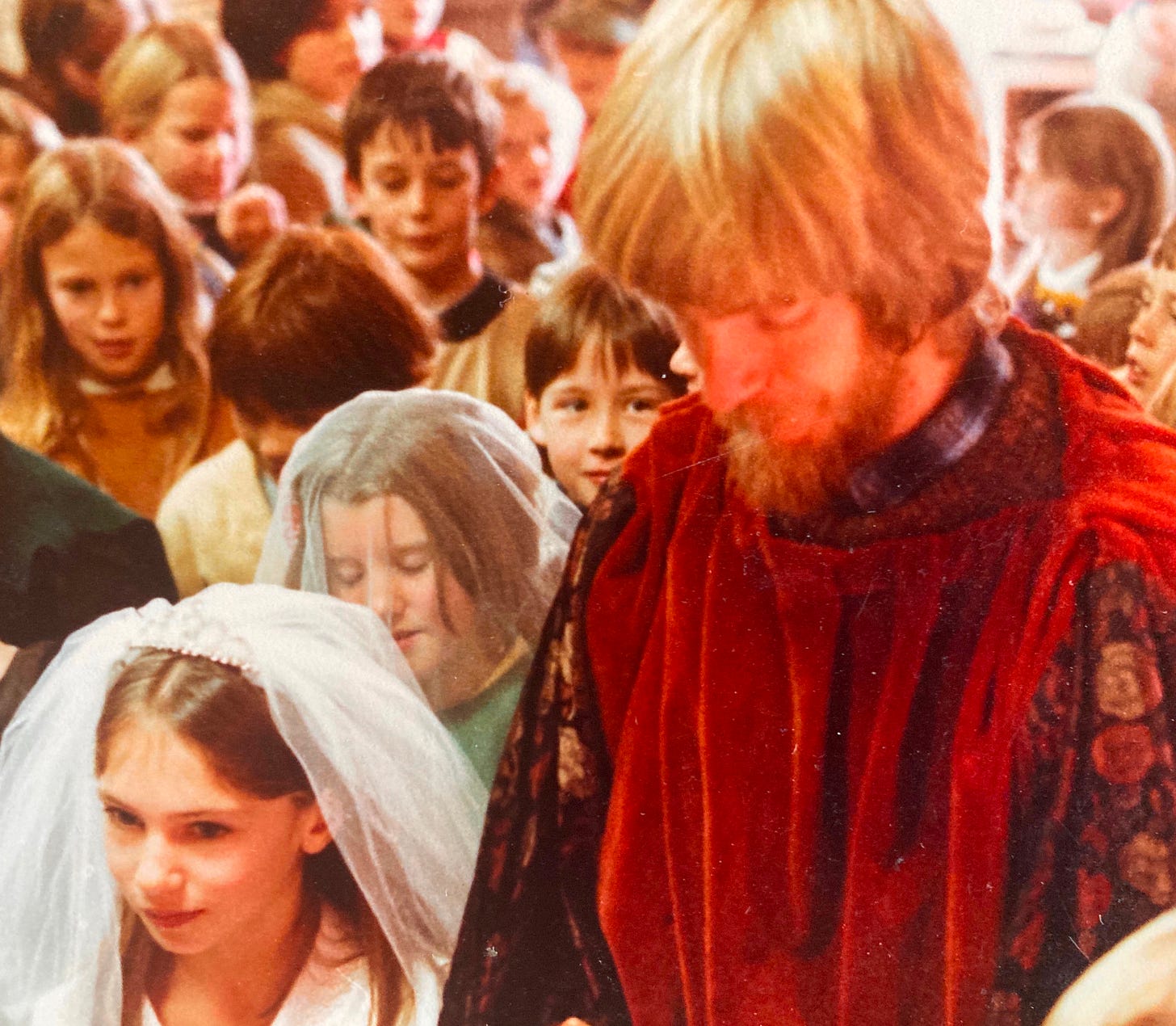

Some subscribers to The Mythopoetic Classroom have been in touch to tell me how much they’ve enjoyed reading (or listening to) School Portrait, my 1987 account of the time my colleague Allen Rooney and I set up a medieval village in our combined classrooms.

Allen was an ex-Preshil teacher.

Sometimes the wound is so deep that the eye’s vision gets distorted. One way of reading School Portrait would be track the ways in which down-to-earth Allen Rooney rescued the overly excitable Steve from a certain kind of tunnel vision!

I love this! It took me years to circle back and return to the place I started from in teaching English - the love of the word, penned quickly, often by kids who were fed up with school and needed to find a way to puncture the routines that encircled them. I learned from their first words and my own feeling but un-informed responses that I knew very little about the vast resource from which they drew their words. This prompted a journey into study of language and how it enables us to make meanings of so many kinds. But it's those first encounters with the possibilities of poetry - stand up, first thoughts, first words - that I return to in my later years. Desire must shape the seeing and the staying with that over the vicissitudes of a lifetime in education. Thanks Steve for this wonderful reflection.

Deconstruction can be torturous, that's why I think support through therapy or a classroom is so important. But I'm grateful that I was given the opportunity to find who I truly am. Thank you for your work, Steven. Ps. 🙃I'm trying to catch up on my list.