What I think I know about reading

I have a queasy feeling in the pit of my stomach. It's linked, I think, with a sense that in these blog posts on reading I'm exposing myself, running the risk of looking foolish.

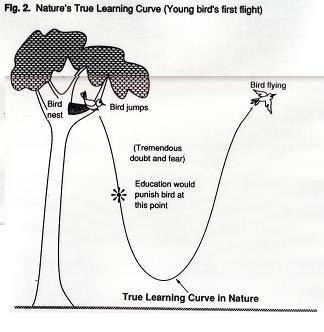

This isn't going to stop me, especially given that I often tell my students that successful learning always takes us into unfamiliar and risky territory. And given that I'm going to ask my postgraduate students to take the same risks, it would be doubly hypocritical to stop now.

But I feel uneasy all the same.

Why foolish?

Well, the world seems full of folk who have thought about, researched and implemented ways of promoting adolescent reading, and the safe way forward for me, as a teacher of 'literacy across the secondary curriculum' to postgraduate trainee teachers, would be to cull the best of what's 'out there', then to present that to my students.

Instead I've decided on a three-step program:

bring to the surface and expose to the fresh air all those preconceptions and assumptions that I make all the time, in my own teaching practice, about how to promote a reading culture in my students;

test those assumptions against the experience of a student (his name isn't Josh, but I'll call him that from now on) who I taught last year and who has agreed to be a part of my short research project;

compare the results of these first two steps with what has been written on the subject.

The queasiness is connected, too, to the risk that what I do in Step 1 (which is the subject of this blog post) will look like either the bleeding obvious or the missing-of-the-bleeding-obvious ... and that this blog post will be somewhat embarrassing to read in hindsight. But I think that's what learning is inevitably like. If we're going to be active learners, we need to take these kinds of risks.

**************

Where to start then? Maybe with a story.

The other day Andrew, one of my Year 11 English students, told me that he found it difficult to engage with our course because none of it seemed relevant to him.

"I've got my life pretty much mapped out," he said, "and I know what I want to be doing in 10, 20 years from now. I can't see where all these books and all this writing fits into that. I can't see any connections."

When we sit down to read with the expectation that the material is going to be meaningful, that it is going to connect us more strongly to what we see ahead of us or alternatively yearn for, then adolescents (like us all) will read. Without this conviction, we read ineffectively and without pleasure or purpose, like Andrew.

Reading a book is like forming a relationship; we should expect that something good will come out of it. Indeed it is not simply like forming a relationship; it involves actual relationships (with a friend, a teacher, a parent or a community), or it feels like it holds out the promise of future relationships.

A boy I taught over 20 years ago suddenly comes to mind.

Dan was 11 at the time. He was full of a confused tension (as I was) between, on the one hand, wanting to be able to read (and therefore focussing on READING and seeing my flash cards and readers as keys to what he desperately wanted to be able to do), and, on the other hand, wanting to be able to be Dan-in-the-world (and therefore focussing on being, and belonging, and connecting, and understanding, and responding). Neither of us saw the strong connections between these two impulses. But suddenly, towards the end of the year and after a sustained imaginative involvement in an exciting classroom project where he had become a particularly active member of our community, he began to read, out loud and to his father, material from the project.

I tell Dan’s story in my book School Portrait.

Experiences in the classroom like these account for certain assumptions I have about reading, and about my role as a teacher interested in promoting adolescents to read more and better. I assume that I do more to encourage adolescent reading by setting up the conditions that will promote connection, knowledge and community (in other words, by concentrating on my subject and on fostering community of learners) than I will by focussing on the reading needs of individual students. The implications of this are:

The more I can infect my class with my love for the subject, the more individuals in the class will want to read. Reading is a means to an end, not the end in itself.

The more my students know about the subject, the more they will want to read, and the more they will understand from their reading.

The more the class inquiry is centred around clearly identified fertile questions, the more purposeful and effective the reading will be.

The more each student feels he can make a meaningful contribution to the learning of the class as a whole, the better he’ll read.

The atmosphere in the class - the sense in which it is experienced as a community of learners and budding scholars - will impact on the amount of good reading done.

Could I perhaps express these implications as maxims, ones that I could then test out in the next two stages of this little research project, when first of all I interview Josh and then I read books about reading?

The more I can infect my class with my love for the subject, the more individuals in the class will want to read. Reading is a means to an end, not the end in itself. Maxim 1: Reading is stimulated by a teacher’s love for the subject matter.

The more my students know about the subject, the more they will want to read, and the more they will understand from their reading. Maxim 2: Prior knowledge is a gateway to reading proficiency.

The more the class inquiry is centred around clearly identified fertile questions, the more purposeful and effective the reading will be. Maxim 3: An inquiring mind directs a reading that is purposeful.

The more each student feels he can make a meaningful contribution to the learning of the class as a whole, the better he’ll read. Maxim 4: We read better when we sense we are agents in the learning of others.

The atmosphere in the class - the sense in which it is experienced as a community of scholars - will impact on the amount of good reading done. Maxim 5: Belonging to a community and the urge to read are linked.

How do I know these things? Because I'm a reader myself, and they are true for me.

Maxim 1: Reading is stimulated by a teacher’s love for the subject matter. Some years ago I read some of the philosophy of Spinoza because a my PhD supervisor's face would soften when he quoted Spinoza. "Steve, listen to this!" he would say, "The love towards a thing eternal and infinite alone feeds the mind with a pleasure secure from all pain. That's good, isn't it! That's a good thought! A fine thing to think about!"

Reading Spinoza wasn't easy, but I persisted and ended up writing an appropriation of Spinoza's Ethics, which I called 'On the natural laws governing learning'. I was infected by my teacher's love for his subject.

Maxim 2: Prior knowledge is a gateway to reading proficiency. There's research about this, much of it sharply critical of reading tests which fail to take this into account. But I'm talking about my own experience here. When I first opened Spinoza's Ethics, I came across sentences like this one: "God (Deus) I understand to be a being absolutely infinite, that is, a substance consisting of infinite attributes, each of which expresses eternal and infinite attributes." I could make neither head nor tail of this. I didn't know what it meant, or why he had written it. Talking with my teacher helped. So did finding out about Descartes and the ways in which Spinoza was reacting to things Descartes had said. Discovering something about Spinoza's life made a difference, too, especially knowing what he rebelled against in his own religious community. Slowly a vague sense of what Spinoza saw as being real and of value began to take shape, and I found myself being able to read the words, to make some sense of them, and to use them as stepping stones to later passages in his Ethics. They began to become pleasurable to me.

Maxim 3: An inquiring mind directs a reading that is purposeful. Ten years ago, as I embarked on my PhD, I was deeply drawn to two questions, one of which had come out of my 20 years experience as a teacher, and the other from some of my personal experiences and from my work as a psychotherapist. The first question was What is the nature of stories, and why are they listened to by my students with such reverence? The second was Why are so many people dizzied by their experience of the world? In one way or another these two questions guided my reading over three years: Freud and Jung, Winnicott and Hillman, Spinoza and Neitzsche. Some of it I found very hard going, but the questions which troubled or excited me kept me focussed. I wanted to know more about things that mattered to me.

Maxim 4: We read better when we sense we are agents in the learning of others. For some years I was an organiser of a professional reading group for teachers at my school. We selected educational books to read and discuss together. We would read the book, usually over a school holiday, and then meet for an extended dinner (in a fine old dining room, the food and wine paid for by our school). One evening, in the midst of an animated discussion, one of the other teachers (someone with whom I often disagreed) said: “Come on Steve, say more. It’s good to hear what you think.” The sense that others valued what I had to say was animating and no doubt encouraged my close reading of subsequent book choices.

Maxim 5: Belonging to a community and the urge to read are linked. Many members of the English Companion Ning are currently reading and discussing together Maja Wilson’s Rethinking Rubrics. There have been hundreds of responses to it, pages and pages of them, and it can be daunting keeping up with the flow, following the different threads, as well as making sure that we’ve read the text itself. Why do I enjoy it so much? Partly, of course, because the ideas are interesting in themselves and I can see ways in which my own teaching is being influenced by the exercise. But it’s also that sense of belonging to a valued community which encourages me to keep reading, to stay connected, to be involved.

**************

So, my assumptions have thrown up five maxims which I can test in my case study with Josh and then in the reading that I do afterwards.

I'm left with a further thorny question, though. What do I mean by 'reading'? Am I only interested in finding out about Josh's experiences with the written word? With books? What about the internet and TV documentaries (both of which Josh mentioned spontaneously yesterday when we had a brief chat)? Am I including in ‘reading’ all those ways in which he pursues knowledge, in which he tries to understand the world better? Am I then, including listening? Viewing? Discussing? Should my course with the postgraduates restrict itself to words on a page, or have a much broader view of what 'reading and writing' entails? If I go the broader definition, how do my maxims stack up then?

Questions for a later post.