Thinking about theory

Theory is all very interesting for some people, and I guess I have to know it because it’s required for our assessments. But really I think what’s going to make me a good teacher is the experience. I learn from doing, not from reading about stuff.

It’s a sentiment I hear a lot from students.

As I slept my way through my undergraduate degree, some forty years ago, it’s a sentiment I used to share. I learnt a little theory in order to pass my assessments. Any deeper connection between theory and practice pretty much passed me by.

But my relationship with theory changed as soon as I started teaching and I realized how little I knew. In some ways, I was like a doctor who snoozed through the lecture on how to treat a broken leg and then found himself in a war zone.

I discovered three important things about theory.

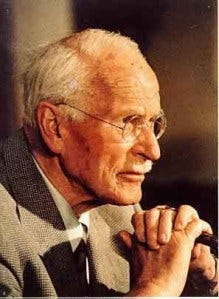

Good theory is consolation. When I found myself becoming overwhelmed, it was wonderful to discover that other teachers had felt similar feelings and were trying to think their way to a more powerful practice. In my early years, I read a lot of John Holt, George Dennison, A.S. Neill, Neil Postman and R.F. Mackenzie, and I discovered a whole community of teachers who struggled with some of the same issues as I did, and who found consolation in exploring relevant educational ideas. It felt better to be a part of a community of such thinkers. Ever since I’ve had a preference for theorists who convey a sense of the complexity and unpredictability of our work (Barbara Comber, Elizabeth Moje, Rudolf Dreikurs, Carl Jung, Howard Gardner, David Perkins) over those who imply that the art and craft of teaching is just a matter of using a model.

Good theory brings courage. We feel most discouraged when we feel alone, without help. In my early weeks with Andrew, I just wanted him to go away; I didn’t know what to do. As I read the paragraphs from Dreikurs’ book about possible motivations behind a power struggle, I no longer felt alone. Dreikurs knew about boys like Andrew! There was a way through this tangle! Even before I’d read about his suggested approaches, I felt a sense of relief and renewed optimism. This was explored territory.

Good theory builds effectiveness. As a young teacher, I kept experiencing situations for which I had no strategies. Discovering ideas that led to more effective action made a difference. Holt taught me that certain kinds of teaching makes children say stupid things. Dennison taught me that apparently random acts of violence in the playground are governed by an intricate set of unspoken rules. A.S. Neill told me that a certain kind of self-government is not only possible but builds a sense of ethics. Neil Postman showed me how to use questions to enliven learning. R.F. Mackenzie encouraged me to link learning to bodies. Each of these ideas changed my teaching for the better.

Good theory does all these three things. Theory learned just to pass a university assessment does none of them.

Jung reminds us that, of course, no theory explains everything.

The moment one forms an idea of a thing and successfully catches one of its aspects, one invariably succumbs to the illusion of having caught the whole. One never considers that a total apprehension is right out of the question. Not even an idea posited as total is total, for it is still an entity on its own with unpredictable qualities. This self-deception certainly promotes peace of mind: the unknown is named, the far has been brought near, so that one can lay one’s finger on it. One has taken possession of it, and it has become an inalienable piece of property, like a slain creature of the wild that can no longer run away.

Jung ‘On the nature of the psyche’ CW 8, 356.

But it would be a mistake to imagine, as I once did, that therefore theory has no uses at all.