Managing doubt and anxiety for a beginning teacher

Two co-authors and I have recently had a submitted article (called Community and conversation: tackling beginning teacher doubt and disillusion) sent back to us for ‘extensive rewriting’ because ‘the implications for teacher education are not drawn out strongly enough’.

To help me think about these implications, I’ve just read a difficult and provocative article by Britzman (Teacher education as uneven development: toward a psychology of uncertainty." International Journal of Leadership in Education, 2007, 10 (1): 1-12) and want to get some thoughts down before they disappear.

Teacher education, Britzman says, is a process full of uncertainty, an experience which is necessarily distressing and usually resisted.

… teacher education is a hated field; no teacher really loves her or his own teacher education. They may soften this rage without a thought by saying, ‘They didn’t prepare me for the uncertainty’. (8)

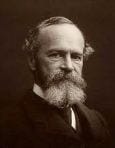

Drawing on the work of Maxine Greene, Donald Winnicott, William James, Hannah Arendt and Wilfred Bion, Britzman suggests that the reasons for this are psychological, social and sociological.

From Donald Winnicott, she borrows the notion that from the moment of birth until we die, we are never complete, we’re always dependent on others, and that this inevitably creates vulnerability, uncertainty and anxiety.

Winnicott (1960/1996) proposed ‘there is no such thing as an infant’ (p. 39). He did so to remind his colleagues the infant comes with caregivers, then toys and the objects that make an infant. Our infancy is made as a relation to others. … There is no such thing as development unless we can begin thinking with, what Winnicott (1970) called in another context, ‘the fact of dependence’ (2).

From William James she cites his ‘big idea’ that it is not in the nature of the mind to be either empty (ready to be filled with knowledge) or stable (developing steadily according to predictable developmental patterns). Instead,

The mind works through the stream of consciousness, through association, and so it is always in motion. The mind will not hold still. This complexity, he said, will be an obstacle to education. For if attention is always fleeting attention, awareness of this psychology makes the teacher’s work difficult. (5)

The experienced teacher, then, plays a vital role in drawing the reluctant and distracted student into the business of learning.

He was not afraid to suggest the need for the teacher’s authority…. The mind that knows, he warns, resists being known…. The mind, after all, is an inter-subjective relation, not an ideal or a thing to fill with knowledge. Good night Descartes: even as we need our own mind to know this, there is no mind without the other’s mind. There is no passion without the other’s passion. (6 )

From Maxine Greene, Britzman uses the idea of the preservice teacher is always in an uncertain state of becoming, having to think him or herself into the unfinished work of attempting to be.

… what is critical only emerges when the teacher understands herself or himself as subject to uncertainty. Uncertainty resides within the acts of a self [which is] committed to becoming. (3)

Britzman uses Hannah Arendt to shift the focus from the nature of the mind or the self to the nature of the world. The teacher, says, Arendt, knows the world, knows that the world is flawed and transient, but also takes responsibility for inducting the student into this imperfect and uncertain world.

Arendt turns to literature and quotes Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Hamlet complained about existence as such when he said: ‘The time is out of joint. O cursed spite that ever I was born to set it right’ (p. 192). Arendt’s conclusion still stuns: ‘Basically we are always educating for a world that is or is becoming out of joint, for this is the basic human situation, in which the world is created by mortal hands to serve mortals for a limited time as home. Because the world is made by mortals it wears out and because it continually changes its inhabitants it runs the risk of becoming as mortal as they. (7)

And finally Deborah Britzman turns to Wilfed Bion, the psychoanalyst and philosopher, who suggested that life brings us face to face with our painful emotional experience of helplessness, dependency and frustration (9), from which we instinctively recoil.

thinking is a way to render valuable one’s emotional experience. (9)

She quotes Bion’s words as follows:

Learning depends on the capacity for the container [by which he means the capacity to hold doubt and not knowing without evacuating the bad feelings this involves] to remain integrated and yet lose rigidity. This is the foundation of the state of mind of the individual who can retain his knowledge and experience and yet be prepared to reconstrue past experiences in a manner that enables him to be receptive of a new idea. (quoted p9)

***

Learning is tough, then, and necessarily involves coming to terms with uncertainty and doubt. Not learning is often the preferred option. Britzman finishes the article with a brief summary of the postmodern university, the place where ‘the idea of knowledge as capable of training minds and as bringing up of culture (bildung) is now obsolete’ and where ‘meta-narratives have worn out’ (10).

With this new instrumentalism comes a new definition of the high speed student. Learners must become adept, flexible, and able to judge knowledge in terms of its use value, its applicability to real life concerns, and its prestige. But this means that skills supplant ideas, technique is confused with authority and responsibility, and know-how short circuits the existential question of indeterminacy. The expansions of multinational and now global corporations into every corner of our lives have terrific force in the university. Students, too, are consumers; they judge the competency of their education rather than their own efforts. (10)

It’s a bleak picture she paints.

How can we think our way into some accomodations with the facts of uncertainty and doubt in such a climate?

I’m left with a supplementary question. If, as Britzman and her cluster of quoted thinkers have suggested, students need teachers to help them cross difficult thresholds (an idea closely connected to Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development, around which so much of our present understanding of good pedagogy revolves), where is the movement in teacher education to increase the quality time teacher educators have with their students, both during their courses as doubts and uncertainties surface, and in their first years in the classroom?

The trend, it seems to me, is in the other direction, with an increase in distance and online education, and a growing list of roles and responsibilities for teacher educators if they’re to meet their Professional Development Review outcomes.

There is no passion without the other’s passion.

But it seems that present realities mean that the other’s passion is not fully available.