Rubrics Part 1: The search for meaning

It sounds so silly, pairing the search for meaning and a rubric. Like deciding what mark to give Anna Kerenina. But this is what we do all the time in our English classes, whenever we’re required to give a grade for a student’s creative work.

This is what I have to do today: create a rubric for a digital story that we’ve asked our Year 11 students to make. I wrote about these students and their course in my last post.

Right now I don’t want to get into the question of whether or not we should give grades for these kinds of pieces. That’s another topic. I have to give a grade.

Instead I want to think about another issue. Can we assess this digital story in a way that encourages honesty and supports a genuine search for meaning? And, in particular, might a rubric help?

These questions are especially important to me right now because of the nature of this particular course. The boys have been exploring a number of central questions.

Why are certain texts valued?

What makes a classic?

Who or what determines meaning in a text?

They are questions which attempt to take us into the battleground between the postmodernists who say that all value and meaning is relative, and the traditionalists who tell us that we frequently read texts ‘in quest of a mind more original than our own’ (Harold Bloom). It’s difficult, challenging work. It’s also necessary, given the influence of both postmodernists and traditionalists in the senior English course which the boys will do in their final year at school. The students (and I) struggle with unfamiliar and uncomfortable ideas; they (and I) feel tremors in the ground we once thought was solid.

One of last year’s students described this struggle beautifully:

I found that the long period of time devoted to this part of the course in 2008 allowed me to repeatedly change my attitude towards the questions that were being asked. I went from having never really thought about why texts are valued, to thinking that it had something to do with a text's capacity to sustain differing meanings and interpretations, to a very culturally deterministic position, and eventually to a fragile and unsatisfactory impasse between subjective emotions and cultural pressures. I went from not really understanding the main text (Studying Literature by Brian Moon), to agreeing with pretty much all of it, to challenging some of the major assumptions behind it. The most important thing about development of understanding was that it gave me a long-lasting interest in, and respect for the complexity of, the questions that were being asked. But this did take time.

It was for this reason that we have decided against asking the students to write an essay. It’s way too early. Instead, because we want them to think about (and learn from) their wobbly thinking and tentative wonderings, we’ve decided to ask them to create a digital narrative. “Working in small groups”, we’ve asked them, “create a digital narrative which tells the story of your journey during the first 7 weeks of the course”.

All of which brings me to the central questions I’m asking in this post. How will we mark this? What are we valuing here? What might a marking rubric look like?

Recent online conversations with Maja Wilson (author of Rethinking Rubrics in Writing Assessment) and a re-reading of the responses to (yet another) wonderful conversation on the English Companion Ning (this one called ‘Standards of writing’) have helped get rid of some of my fuzziness around the issues.

Maja Wilson (and others) have pointed out the need to distinguish between two categories: our ongoing responses and interaction with our students in what she calls our ‘interpretative communities’ (responses and interactions which develop our – students’ and teachers’ - thinking and deepen our understanding) on the one hand, and on the other our grading at the end of the process, which attempts to identify a stage reached. As Daniel Sharkovitz put it in the Ning discussion:

If we hide our responses to student work behind rubric masks, we will fail to give kids perhaps what's most important in our response--the response itself.

So I have to keep reminding myself that the marking of this digital narrative task mustn’t be the sum total of the feedback I give my students about their experience of the course. It’s just the bit at the end. Secondly (and, if I’m understanding her right, this is again connected to Maja Wilson’s point about interpretative communities), the marking rubric needs to be the result of a shared understanding between students and teachers of what the goal is, and of what is valued in the attempt to achieve the goal.

In this case, we’re wanting the students to tell the story of their experience of our course; that’s the goal. And we have two values: honesty and the ability to engage an audience. We’re not (at this point of the course) interested in how well the students have grasped particular ideas, engaged with the texts or managed the routine and expectations of the course. We just want them to tell a story, and to tell it well.

So, will a rubric help? My sense is that it will, particularly if I publish a draft rubric and ask students to help me refine it. Doing this will get us to refine our values and our shared thinking about what this task is all about.

[There’s a wonderful irony implicit in this attempt. The course is, in part, an exploration of postmodern notions that the meaning of a text is largely determined by the reader, by the context, and assumptions and values he or she brings to the reading. By asking the students to create a digital narrative, and by putting myself in the position of a marker of that text, I’m saying that I believe the student has created the meaning and that the success of his text can be measured by the extent to which I have ‘received’ his meaning. In other words, the very marking of the piece positions me as a traditionalist rather than as a postmodernist. How would I respond if a student genuinely took a postmodernist perspective and challenged my right to do this? I think I’d have to take this as evidence that he had truly understood one of the possible perspectives our course teaches!

And, as I write, I can feel the slippery elusiveness of trying to capture the uncapturable, of trying to write a rubric which helps us evaluate creative work. But I’m going to have a go, even though by the end of this post I might be empty-handed.]

I’ve had a look at a rubric for digital story-telling, one that Kelli McGraw drew my attention to. It has categories for point of view and purpose, voice and pacing, images, economy and grammar. But I’ve got Dan Sharkovitz sitting on my shoulder saying:

let me offer you the one standard that I have been able to commit to memory, sort of. Certainly, it has helped me help my students … To be clear about my own bias, I came along during the days of Strunk and White, and the "vigorous writing is concise" mantra. And I thought if I really believe that, why use nine words if six will do? Why write thousands of standards, if one will do. Here it is, the one standard that I have actually been able to memorize: When students compose a text, they will use whatever is necessary to achieve their goal.

These words remind me, as I sit down to draft this rubric, that this is a creative task, that the goal is to tell a story, and that there are many different ways to achieve this in a digital narrative. One might rely on the images almost exclusively (in which case the rubric’s grammar categories are irrelevant and would derail those students who are overly constrained by what the rubric says). The same applies to a student who wanted to tell the story essentially through (a limited number of) words; he might feel obliged to provide music (if it’s mentioned) or come up with a balance of elements: words, music, images. The point here is that there are a thousand different ways of telling a story using the digital narrative, and the students should feel free to use ‘whatever is necessary to achieve their goal'.

[Is all this thinking helping, or am I just procrastinating? I’m not sure that I care all that much. It’s pleasurable thinking. It’s thinking that connects me to conversations - with Maja, Kelli, and Dan, soon with my students, and also with anyone else who cares to join in - which give me a delicious sense of belonging to a community of inquiry.]

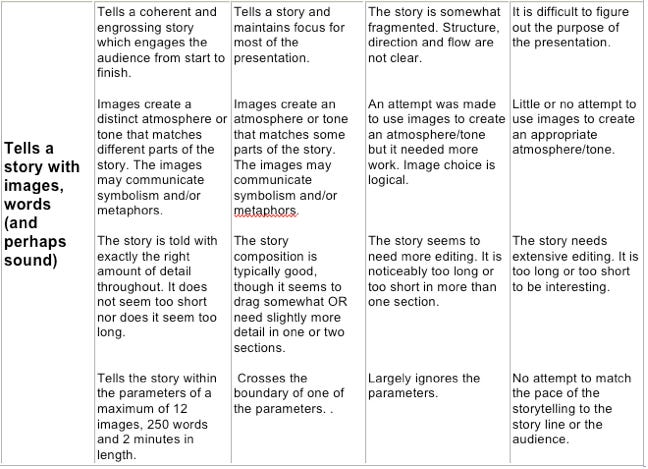

So the goal is explicit (to tell the story of an experience of the course), and the values are out in the open as well (to tell it honestly and to communicate the student experience clearly and engagingly). There will be details as well: that it takes no more than 2 minutes to watch, with a maximum of 12 images and 250 words.

[I’ve never made a digital narrative myself. I should have a go. Maybe that’s my next blog post?]

There’s one final consideration. For reasons that are a bit foggy , we (the three teachers involved planned this assessment about 4 months ago) decided to make it a group exercise. In groups of around 3 students, they produce one digital story which tells the stories of all the group members. [Or could it be a digital story that tells the story of one of the group members? I think this would be fine. Yes, we want the students to reflect on their own experience, but if the group chooses to write one story rather than three, then inevitably all three will find themselves thinking about their own experience. I think we should leave this open.]

Anyway, it’s a group exercise. Maybe one student will look after the technology, another think through how the story might be told, and a third could be the co-ordinator of the project. However they do it, the group aspect is important. Does it need to be reflected, then, in the rubric?

Let’s see. Time to have a crack at it…

***************

At which point, an interesting thing happened. The more I worked on the rubric, the more I found myself being drawn back to Kelli McGraw’s original. Here's my adaptation of her rubric.

So, there’s the draft. The crucial next step is to involve the community in its evolution. Does it accurately reflect the goal of the exercise? Does it reflect the values we hold?

We won’t be able to tell, of course, until my two teaching colleagues and the students see it. Then, with a dose of good luck and perhaps some careful management, we might move from a draft reflecting my meandering thinking and Kelli’s careful construction to something that is the work of one of Maja’s interpretative communities.

Does the rubric have the potential to help our search for meaning in our Texts-Culture-Value[s] course?

***************

And just as I was about to press POST an hour or so ago, I happened to notice another discussion on the English Ning, one that I hadn’t seen before, this one called ‘Rethinking Rubrics in Writing Assessment’, where Maja Wilson writes:

Often, I don't know what I value until I bump into it, so how could I possibly articulate all my values before-hand, even on a self or student generated rubric? I heard Tibetan throat singers on the radio years ago for the first time and had to pull my car to the side of the road because I was weeping. I'd never heard the sound before, and it moved me deeply. I wouldn't have been able to tell you two minutes before I heard it that I valued anything about that unearthly sound. Imagine if that throat singer had read my set of "values" about singing, and decided not to do his gravelly resonant thing because my rubric indicated I wouldn't reward it?