The mythopoetic function of storytelling

We dimmed the lights for the 150 education students in the lecture hall, I paused for a few moments to get myself out of the day-to-day and into the storytelling space, and then I began.

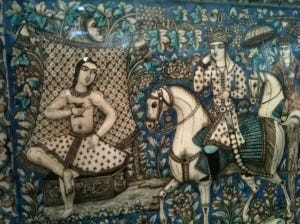

Once upon a time, a strong and powerful Tzar ruled in a country far away. And among his servants was a young archer, and this archer had a horse – a horse of power, a great horse with a broad chest, eyes like fire, and hoofs of iron. Well, one day long ago, in the green time of the year, the young archer rode through the forest on his horse of power. The trees were green; there were little blue flowers on the ground under the trees; the squirrels ran in the branches, and the hares in the undergrowth; but no birds sang. The young archer rode along the forest path and listened for the singing of the birds, but there was no singing. The forest was silent, and the only noises in it were the scratching of tiny four-footed beasts, the dropping of fir cones, and the heavy stamping of the horse of power on the soft path. "What has come of the birds?" said the young archer. He had scarcely said this before he saw a big curving feather lying in the path before him. The feather was larger than a swan's, larger than an eagle's. It lay in the path, glittering like a flame, for the sun was on it, and it was a feather of pure gold. Then he knew why there was no singing in the forest. He knew that the firebird had flown that way, and that the feather in the path before him was a feather from its burning breast.

The firebird, the horse of power, the Princess Vasilissa

For the next 30 minutes or so, I told the story that I had been learning pretty much off by heart. After it had finished and I got back to my room, I found that a colleague who had been present at the lecture had sent me an email.

You broke all the rules, you know. Academics don’t begin a year’s course like that. It was uncomfortable, unsettling, and I watched as, at the beginning, a number of the students in the lecture hall reached for their mobile phones, or swapped puzzled looks. I was uneasy myself, and found myself struggling with my own cynicism and impatience. At first I wanted the story to move faster. Yet I found that your story-telling put me in a different time and place. I'm not sure it's my time and place, but once I let my resistances loose from their moorings, once I dropped my cynicism and doubt, I did notice that I'd entered the dreaming realm, where connections are made and many things are possible.

In the week that followed (last week), I listened to the students as they talked and wrote about their reactions. A couple were incensed by the implicit sexism or questionable political and moral messages.

… it did irk me that the archer got an entirely happy ending and did not seem to learn any particular moral lesson - he did the wrong thing initially picking up the feather, then he captured a beautiful innocent bird, then he kidnapped a girl, whilst the Horse of Power solved all of his problems for him and the archer triumphed and reaped all of the rewards in the end.

Others were impatient with all the repetitions, and talked about how, in today’s world, stories are told quite differently, not just with words but with sound and fast-moving images.

My response to the story was less about what the story could mean and more to do with my own feelings while listening to the story. I found it hard to settle into listening mode and felt myself more interested in the responses of the people sitting around me. Some people were concentrating on Steve and you could tell that they were listening intently. Others around me were fidgeting and seemed to be looking to others for reassurance. It was a strange situation for the majority of the lecture. For most of us, storytelling without accompanying images or sound is uncommon.

Some enjoyed the ‘time and place’ created by the story and found themselves thinking about it afterwards.

... it seemed to reflect one of the assumptions that I bring to the course and that I had been thinking about, that (in my opinion) some of the real learning that I have done has been facilitated by something that was stressful - whether it was a test, exam, trying something new, getting out of my comfort zone, being wholly responsible for something - and this is both in education and in employment.

Finally, many wondered why I had told it, and what was the moral of the story. This is a common reaction, an offshoot (I believe) of our living in a society that values the instrumental above the mythopoetic. We are taught (partly through the stories we are told when we’re young) that every story has a moral, that the purpose of storytelling is to teach children the rational rules of living together. We have lost touch with the other function of stories (and dreams), which is to put us in touch with the mythopoetic. This is less to do with how we ought to live and more to do with how life (even the life of the invisible and unconscious) actually is. Stories are like dreams. They reflect (often in weirdly wonderful ways) hidden realities about life. At the beginning of the story, the Horse of Power tells the young archer ‘Don’t pick up the feather. If you pick up the feather, you will know the meaning of trouble.’ The archer picks up the feather, and the Horse of Power then guides the young archer through all the trials that comes his way. This is enormously confusing if you’re looking for the moral of the story. Should we listen to advice, or ignore it? Should the archer have been punished for picking up the feather, or rewarded? But if we approach the story in a quite different (mythopoetic) frame of mind, it’s not confusing at all. If we think about the characters in a story as if they are all different aspects of the one consciousness (different parts of ourselves, if you like), then the fact that we have a voice inside us that tells us ‘don’t take risks’ and another that says ‘live life to the fullest, even if that means a less secure existence’, makes perfect sense. One of the reasons I told this story at the beginning of a teacher education unit is that my students arrive with a cacophony of competing voices in their heads, a mixture of yearnings and doubts about what a university course can give them, of hopes and fears about what this choice to become a teacher might involve. One of the students put it this way:

Perhaps also when we have suspended belief in the real world logic and science, we have left space in our minds for the content of the story to move in, often bringing with it useful knowledge or behaviours. I don’t think it is Steve’s intent to pass on a moral message with this story, perhaps he merely wants us to be left thinking of as many reasons this story could be relevant as possible.