This post is going to make more sense if you have already read the post called The inner world of students. Part 1: Ben

I wrote the account of my time with Ben as part of a 1995 Masters thesis. I thought it might be fun (and might just work!) if I included in my thesis fictional letters that I received from luminaries like Carl Jung, Joseph Campbell and James Hillman, each commenting on what I’d written about students like Ben.

In my thesis, I wrote to Joseph Campbell as follows:

Dear Joseph Campbell,

When I work with children I am drawn to the world of story. If I understood more about this relationship – story to psyche, myth to energy – then perhaps I would know more about why Ben listened to the story of Iron John with such rapt attention, and why the changes I’ve documented took place at the time that he was fantasising about keys and robots and wild lions and while he was listening to the story of Iron John.

Yours sincerely,Steve Shann

My imagined Professor Campbell responded (in part) as follows:

Dear Mr Shann,

Goodness! This is no simple task you impose, one that takes us to the edge of mystery, to the edge of what we have words and ideas for, to the edge of what we have the ability to comprehend. But, like the intrepid hero of a thousand faces, the hero who sets out on the impossible task into territory full of frightful danger and dark forests, let us go to the edge and, if we cannot make out with any clarity what moves the forces and energies of the unfathomable land that is the human condition, at least we may return from our journey with a more lively and present appreciation of the unseen forces that move below. For as soon as we investigate myth, we find ourselves enveloped in mystery. The fog closes in, strange creatures appear and according to their disposition they either beckon us on or warn us off.

Ben was stuck in an infantile rage. He was being controlled by it. He was fixated to the unexorcised images of his infancy, and hence disinclined to the necessary passages of his childhood. The Freudians suggest that analysis and a kind of confrontation will break the spell and move the child onward. That may well be so. It is my contention that myth, too, can serve this function.

Some years ago, scientists conducted a most interesting experiment. They were working with grayling moths, and noticed that the male grayling moth would almost invariably be attracted to the darkest of several females. Would the moth prefer an artificial moth to a real one, they wondered, if the model were darker? An experiment was conducted where a model moth, painted darker than all the female moths in the cage, was introduced. The male moth preferred the model.

Now what does this have to do with Ben’s infantile fixations and the story of Iron John? Well, just as invention can stimulate a moth's instincts, so does human art stimulate our own - in dream and nightmare, but even more brilliantly in the contrived folk tales, fairy tales, mythological landscapes, over- and underworlds, temples and cathedrals, pagodas and gardens, dragons, angels, gods, and guardians of popular and religious art. Stories can stimulate a response in us which might be called biological and which gives us strength and energy to face life’s challenges. We carry the story within us, and we respond with a quickening of our metabolism when we hear the story told. It has always been the prime function of mythology and rite to supply the symbols that carry the human spirit forward, in counteraction to those other constant human fantasies that tend to tie it back. In fact, it may well be that the very high incidence of neuroticism among ourselves follows from the decline among us of such effective spiritual aid.

Myth and folk story are expressions of biological impulses that come from the ground of our being. The energies of the universe, the energies of life, that come up in the subatomic particle displays that science shows us, come and go. Where do they come from? Where do they go? Is there a where? Mythology opens up the world so that it becomes transparent to something that is beyond speech, beyond words. And when the world is opened up in this way, we feel ourselves connected to something fundamental to our natures.

It seems to me, from reading your case study, that Ben was being companioned into this mythological realm, the world of the gods. He follows the same pattern as the hero of all stories: initially reluctant to obey the call to adventure (the prince wants to stay in the castle); the decision to go (the walks into the forest full of monsters); the finding of allies (you and Bella); the encounter with guardians at the gate into the magical realm (his school experiences, his doubts about himself); the quest (for the key to wildness); and the return home with the gift or boon (his decision to end his sessions with you). This is the pattern of the myth, just as it is the pattern of certain powerful fantasies of the psyche. A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow men.

The point I am making here is that story actually serves a biological function. As this is an unusual claim, let me come at it again by analogy, this time using your Australian kangaroo. Since these are not placental animals, the foetus cannot remain in the womb after the food provision (the yolk) of the egg has been absorbed, and the little things have to be born, therefore, long before they are ready for life. The infant kangaroo is born after only three weeks of gestation, but already has strong front legs, and these know exactly what to do. The tiny creature, by instinct, crawls up its mother’s belly to her pouch, climbs in there, attaches itself to a nipple that swells (again instinctively) in its mouth, so that it cannot become loose, and there, until ready to hop forth, it remains in a second womb. An exactly comparable biological function is served in our own species by a mythology, which is no less a nature product, though apparently something else. Like the nest of a bird, a mythology is fashioned of materials drawn from the local environment, apparently altogether consciously, but according to an architecture unconsciously dictated from within. Its comforting, fostering, guiding images have as their function to prepare an unready psyche to maturity, preparing it to face the world. Its next function must be to help the ready youth step out and away, to leave the myth, this second womb, and to become, as they say in the Orient, ‘twice again’, a competent adult functioning rationally in his present world, who has left his childhood season behind.

Why did this particular story, the story of Iron John, speak so strongly to Ben? It is, I think, because the story answered for him the one question that plagued his life. What do I do with all this bad energy that takes hold of me? I cannot wish it away. I cannot master it through an exercise of self-discipline. How can I transform it, so that what was once destructive can fill my soul with a different kind of impulse, no less strong but more conducive to me functioning in the society in which I find myself?

The answer, Ben would have felt, was to be found in the experience of Iron John himself, the magical god of the story, the focus of the story’s energies. At the beginning, in the king’s wood, Iron John is under a spell, out of control, in the grip (if you like) of infantile fantasies. He murders hunters and their dogs. But, as in stories like ‘The Beauty and the Beast’, the boy sees in the monster something other than the outward skin. He lets him out of the cage. He goes with him into the forest. He attempts to guard the magic spring. As he does these things, he forms a relationship with the monster, and the monster with him. The monster changes. The wild and uncontrolled passions which led to the initial murders are replaced by an unsentimental attachment to the boy. Tasks are imposed, help is given. Iron John changes from beast to task-master to ally and finally to benefactor, taking up in turn four of the many masks of the gods. Iron John is the link between the boy’s everyday life and the mysteries of the unseen world, the source of all life and being and energy.

The deity in a story is, like Iron John, a personification of the energy. It’s a personification of an energy that informs life. All life, your life, the world’s life. Those who have heard deeply the rhythms and hymns of the gods, the words of the gods, can recite those hymns in such a way that the gods will be attracted. Ben changed over that time because he heard the words of the gods and he found a way to voice incantations (in the form of fantasies) that brought the hidden and inexhaustible energies of the cosmos into what I have called ‘human cultural manifestation’. And into his life.

There is a question you implicitly ask in your case study about your role. Are you a teacher or a therapist? It is, in my view, a false dichotomy, for to be a teacher – someone who passes on cultural understandings and values through the stories he or she tells about the material and invisible worlds – is to be a therapist – someone who helps train up a character fit to live in this world as it is. The first function of story is to foster an unready psyche to maturity, preparing it to face the world, to waken and maintain in the individual a sense of awe and gratitude in relation to the mystery dimension of the universe, not so that he lives in fear of it, but so that he recognises that he participates in it, since the mystery of being is the mystery of his own deep being as well. Ben felt alienated from all this at school. He felt cut off, different, bad, shunned, out of control, out of context. During the months that he worked with you, he found himself being included. As he looked at the mythological figures on your shelves dancing their wild dances, as he saw the red masks on your walls shouting their angry rage, as he told stories of wild and murderous impulse, and as he heard a story about a prince and a wild man that sounded like the drama raging inside his own breast, he was brought back into connection with the world. He no longer felt alien, a misfit. The correspondence between his internal fantasies and the motifs of the stories you told him taught him that he belonged not just in the safety of his mother's embrace, but in the world beyond the hearth as well. As storyteller and soul companion, you are teacher and therapist together.

This is the message that stories give to children like Ben: have courage, be not afraid, either of the universe within or of its manifestation in the wide world which is drawing ever closer. For where on the adventure we had thought to find an abomination, we shall find a god; where we had thought to slay another, we shall slay ourselves; where we had thought to travel outward, we shall come to the centre of our own existence; where we had thought to be alone, we shall be with all the world.

Kind regards

Joseph Campbell

______________________________________

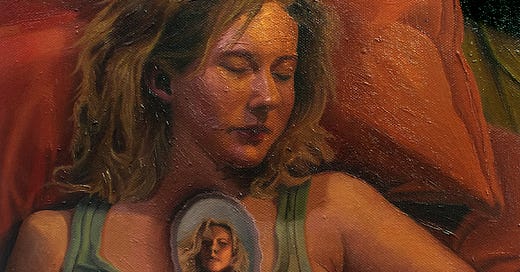

The painting at the head of this post is by Solomon Karmel-Shann.

I choose these paintings for my Newsletters not because they illustrate what I’m writing about (though occasionally they happen to), but because I like having my son’s marvellous paintings scattered around the home page of my site.

Solomon was recently awarded one of six 2024 Brett Whiteley Travelling Scholarships.