Secondary English: lost in the forest?

1.

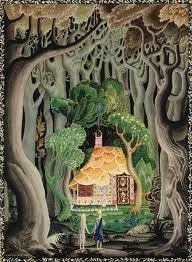

As with all good mythopoetic literature, a folk story is layered enough to contain many meanings, and the story of Hansel and Gretel is no exception. This morning it came to mind as I was thinking about an article I’d just read about English teaching.

First the article.

It is called ‘The Challenge of English’, and it’s written by a senior English teacher at a Victorian private school. (It’s a school that I have a family connection with, as my grandfather was once its Headmaster and my father was brought up on its grounds.) The author gives advice to Victorian students beginning their final year of English studies.

First he describes the nature of the English course. It is, he says, ‘an English course that develops a variety of language, interpretive and writing skills. It is a course based on the use of language; every outcome has language at the heart’.

He then explains how best to tackle the course. There is an implicit metaphor in the way he describes this course, that of a scientist observing, dissecting, describing and analysing an object.

Students need to have a mastery of their texts [in order to develop] insights into the key themes, characterisations and ideas of the text. [Students need to] have a thorough understanding of the structures, features and conventions used by writers or directors to construct meaning …. In what ways do the narrators present their stories and what are the limitations of their narration in respect to biases, personal beliefs and their world as they understand it? This is the sort of question a thoughtful VCE student should be asking. [With the section of the course devoted to the language of persuasion], the task of the student is … to surgically analyse [the language of texts] to demonstrate an understanding of the ways language and visual features are used to present that point of view.

This is all good, sound advice. Given the nature of the English course, and the way student responses are marked against explicit and measurable outcomes, to advise anything different would be irresponsible.

But the subject has wandered far from where it has its home.

And that’s where the story of Hansel and Gretel comes in.

2.

In the story, all at home is not beer and skittles, and the children – Hansel and Gretel – are forced to leave and venture into the forest. They attempt to find their way back, but in the end are lost deep in the forest where, desperately hungry and tired, they stumble across a small house, tantalizingly made of bread, cake and sugar. As they begin to eat the house, an old woman comes out of a door, a woman who seems kindness itself.

The old woman, however, nodded her head, and said: 'Oh, you dear children, who has brought you here? Do come in, and stay with me. No harm shall happen to you.' She took them both by the hand, and led them into her little house. Then good food was set before them, milk and pancakes, with sugar, apples, and nuts. Afterwards two pretty little beds were covered with clean white linen, and Hansel and Gretel lay down in them, and thought they were in heaven.

It turns out they’re not in heaven at all, but in the clutches of a cannablistic witch.

Then she seized Hansel with her shrivelled hand, carried him into a little stable, and locked him in behind a grated door. Scream as he might, it would not help him. Then she went to Gretel, shook her till she awoke, and cried: 'Get up, lazy thing, fetch some water, and cook something good for your brother, he is in the stable outside, and is to be made fat. When he is fat, I will eat him.' Gretel began to weep bitterly, but it was all in vain, for she was forced to do what the wicked witch commanded

3.

What was it about the newspaper article that had me thinking about the story of Hansel and Gretel?

It’s been my sense for some time that secondary English teaching, as it has been represented in curriculum documents and assessment protocols, has lost its way.

It’s been cut off from its home (more about that later), and, in its search for some kind of recognized position alongside valued school subjects like maths and science, has tried to establish itself within the neoliberal discourse.

It’s found itself feasting on a house made of cake and sugar. It has been seduced by the promise of rubrics and measurable outcomes into thinking that its real value lies in its potential to raise literacy standards and teach communication skills.

For a while outcomes and rubrics gave us some relief, a sense that we could explain to the students what we were looking for and how they could succeed in our subject.

But, instead, we find ourselves in a place where we’ve lost touch with our true home, the deeper essence of our discipline.

Which is what?

I’d like to come at this (in an attempt to do what good stories do) meanderingly.

4.

Last weekend I read Jeanette Winterson’s Sexing the Cherry. There’s so much in that book that made me think, both about my own life and about the world in which I live.

That’s the thing about great books, isn’t it; they make you think, they help you to see more, they give you words for feelings or intuitions that until then had remained below the surface. They help nudge us towards a greater connection with the world: the world out there or the world inside.

At one point Winterson has one of her characters say:

I have set off and found that there is no end to even the simplest journey of the mind. I begin, and straight away a hundred alternative routes present themselves. I choose one, no sooner begin, than a hundred more appear. Every time I try to narrow down my intent I expand it, and yet those straits and canals still lead me to the open sea, and then I realize how vast it all is, this matter of the mind. I am confounded by the shining water and the size of the world.

This reminds me of Digger in David Malouf’s Great World, who was ‘dizzied by the world. He could never, he felt, see it steady enough or at a sufficient distance to comprehend what it was, let alone to act on it. ‘

And this, in turn, reminds me of Spinoza, who said that our limited faculties mean that we are only able to comprehend a miniscule portion of what is, a tiny bit of the vastness that only ‘the eye of eternity’ can take in.

Reading these things doesn’t just help me make sense of my own confusions. They connect my experience to that of others. I am consoled that it’s not just me that finds things so complex, so dizzying, so endless.

Reading these things tells me something about the nature of the world. Ironically, I end up knowing more, being less dizzied, more able to join in.

I do not read these books in order to dispassionately observe, dissect, describe and analyse. They are not objects like that.

Instead they are minds with which I strive to have some kind of relationship; they are voices I listen to in order to know more about the world that I’m in.

The focus here is not on the text-as-object, but on what happens when I, as reader, open myself up to a conversation which involves trying to see the world as the writer, or one of the writer’s characters, might have seen it, or to understand something more about a character's - and therefore a human - experience .

I’m not outside, looking in at the text. The text and I are standing shoulder to shoulder, looking together at the world and sharing thoughts about it.

English has lost its way because its become text-centric.

The proper object of study for any discipline is not, as the teacher’s article above implies, the text; it is the world in which we live, and we enter into a relationship with useful texts only in order to help us understand that world just that little bit better.

I want to explore this idea some more in my next post.