Rubrics Part 3: a noun or a verb?

A noun or a verb?

Is a rubric a thing that we create (whether to give transparent feedback or to limit the creativity of our students, depending on your viewpoint)? Well, of course it is! 'Rubric' is a noun. Any dictionary will tell you so.

But what happens when we think about it as if it were a verb? I don't mean this literally, of course. There are too many good nouns that have been turned into pretty awful verbs, and I'd hate to hear someone suggest one day, "Hey, let's rubric this, shall we?"

I mean something very different. I'm wanting to highlight the change that comes when, instead of thinking of a rubric as an object which is created by a teacher and then used to give feedback and evaluate student work, we think instead of the creation of a rubric as a collaborative act that fosters community, as something which (verb-like) describes an action (or, more accurately, a process) rather than an object.

Too theoretical?

I want to tell a story to bring this back down to earth.

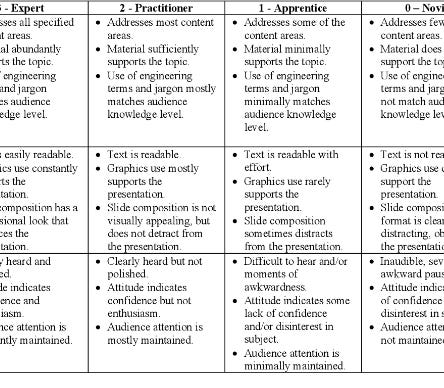

A week or so ago I drafted a rubric and described this in a blog post, which I posted here and on the English Companion Ning. I also shared it with my colleagues at school and with the students.

The responses I got here and on the Ning ranged from suggestions about amending the rubric to thoughts about the way rubrics limit the creativity of our students and avoid the really important feedback that students need. I won't describe in detail the excellent points made - I think they're worth reading in full. Most of it, though, led me to understand something new about the issue of rubrics. I think it contributed, too, to the students' thinking about creativity and the struggle teachers have to respond constructively within the constraints of the systems that dictate some of what we do.

I want to give an example.

In the draft rubric (it was for a digital narrative), there was a clear implication that the students' digital narratives should be 'coherent', that their stories should told in a way that avoided fragmentation. Dan Sharkovitch responded on the English Companion Ning as follows:

On your other blog you have a rubric. One element speaks to a student's ability to write a "coherent" story as having more value than one that is "fragmented." Those terms are profoundly problematic for a writer. Many of the short stories in Denis Johnson's postmodern collection, Jesus' Son, are in fact fragmented (e.g., Car Crash While Hitchhiking). Virginia Woolf, in To The Lighthouse, creates a narrative structure where, as Auerbach noted in "The Brown Stocking," that Woolf's writing evokes the shifting, fragmented nature of human consciousness because her narrative is fragmented.

This worry was echoed by one of my students when he saw the draft rubric, in particular when he saw that we were thinking of limiting the digital narrative to 12 images. 'This doesn't fit in very well with what I've done so far," he said, and he described a plan to base his digital narrative around a frentic Dr Seuss book idea, where his experience of our course so far (which is the subject of these narratives) was fast-paced, fragmented, confused by divergent ideas coming in from all sides.

And so we've changed the rubric. We've ditched the limit of 12 images ... and we've had a discussion about the appropriateness of a fragmented narrative when that's the kind of experience the narrative is wanting to describe.

All of which brings me back to the 'noun' and 'verb' idea. Rubrics as objects have a limited (and sometimes a negative) effect. But when they're thought about as triggers for a process for reflection and evolution, then maybe they have a part to play in what I rather grandiosely called in my first post in this series 'Searching for meaning in our English classrooms'.