I'd kept a diary from time to time during my fifteen years as a teacher, but at the beginning of the 1982 school year I decided to try something a bit different. In the past, I'd written about general events in the class and my reactions to them, and only occasionally about a particular child. I might find it helpful, I thought, if I followed the progress of four or five of the nine-year-old children in my class over the course of a term or a year.

But which children? I wanted a group that, if possible, reflected the diversity in the class itself. So I chose Dan because he was struggling with his reading, and Kate because she was highly articulate and literate. Anna had a sense of the dramatic and an openness that I enjoyed during those first days of term, whereas Chris had some kind of a barrier which I found hard to penetrate. And Paul, when he came into my class in 1983, chose himself. He was one of those people who grabbed the spotlight, and either captivated or infuriated those around him.

I wrote in that diary almost every day for a term, and less regularly after that, until, in 1984, I recorded the daily progress of our medieval village, the simulation described in the second half of this book.

It was at about this time that I began to think about using the material in my diaries for some kind of book. But exactly what kind of book I wasn't sure. Certainly one that told the story of the medieval village, perhaps centering around the school lives of Dan, Chris, Anna and Paul. (Kate was no longer in my group.) I was sure that something could be done around that. But there were other things too.

I wanted to write about my own professional life during that time: of my attempts to understand the children better; of my growing unease about some assumptions our society holds, and in particular the notion that education can be packaged into logically ordered and attractively presented curricula by adults, and then dished up to children; of my increasing awareness that each of these children had a powerful and natural urge to learn, as did the other children in the class, which sometimes I attempted to redirect into barren and narrow channels.

As I worked with these children and got to know them better, as they reached out to understand the social, intellectual and physical world around them, and as they struggled with the expectations which they and their society had for them, I found myself continually coming back to the same three questions. Are there really skills, attitudes and knowledge which we adults need to isolate, analyse, organize and package into a core school curriculum for the children? Or should we adults be starting somewhere else, with the children themselves, with each child's unique experiences and interests and strengths and needs, and somehow building our school experiences on these? And if so, how?

The popular press writes as though the progressive movement in education has had its chance, and that it's time we got back to the basics. From my perspective, the movement for real reform in the schools has not yet begun. What writers now point to as evidence of change in school is still, in my view, mutton dressed as lamb, the old assumptions about how children learn and what our society requires seasoned with a garnish of computers, 'new maths', open plan architecture, new methods of assessment, and the like. There are many individual teachers in all sorts of schools doing humane and helpful things with the children in their classes. But the school structures, and in particular the assumptions about learning which pervade our society, are working against them, making their jobs more stressful, more difficult.

What are these assumptions? I think they can be summarised as follows: there are important social, academic, and physical skills that can be learnt by children in schools; some of the skills can be taught directly by a teacher, and others will be learned from the way the teacher structures the learning environment; skills are best learnt in a systematic way, beginning with what's easiest and most basic, and then going on, step-by-step, to material that is slightly more complex, with the adult always firmly in control of the process, making decisions about what the child will do, and when; if a child is struggling, there may be emotional, physical or intellectual reasons, and an expert (sometimes a teacher, sometimes an outside specialist of some kind) can work out what the problem is through tests and/or interviews, and can point to a remedy; sound educational packages exist or can be put together which enable teachers to ensure that children learn the important skills.

These are, I believe, widely held assumptions, and certainly not restricted to either the more traditional or more 'progressive' point of view. But the more I wrote, and the more I reflected on the experiences of these children, the more I felt that they were misleading. I came to feel, and wanted somehow to express this through the book, that unless we can let go many of these assumptions, then we'll miss seeing important opportunities for children's learning, we'll continue to set up schools which make it harder for children to learn, and we'll continue to train teachers in the wrong skills.

What is misleading about these assumptions? I hope that this book will go some of the way towards answering that question, but perhaps some thoughts by way of introduction might be appropriate here.

It is the view of the child that is implied in them, a view which suggests that the child is the receiver of skills given by the adult. The spotlight is on the quality of the package, the programme, the syllabus, instead of being on the child as an active learner, as a person who brings experiences and perceptions to the classroom.

The truth is, I think, that children (particularly of primary school age) learn less of enduring importance to them from what is taught or intended by teachers and parents than we realise. Children learn from what they do, and from what involves them heart and soul. While this sometimes includes what happens during 'lesson time' at school, it also happens (and sometimes more often) when they're playing with each other, when they're arguing and planning and swapping stories, when they're making and building, when they're painting and writing and drawing about things that grip their interest and imagination. It happens when they're making their cubbies and when they're in their fantasy worlds.

Children learn most when they're most involved. We adults know this is true for ourselves. Most of us can talk about events or processes that have involved truly significant learning for us because they were connected with what we really cared about and were deeply interested in. But we worry about applying this to children in case they miss out on learning that maybe isn't fun but which is important nonetheless.

If left to themselves, perhaps some children wouldn't have the courage to attempt what is hard, challenging, a bit frightening. Perhaps we, as adults, wouldn't either. But surrounded by other people (adults and, very importantly, other children) who are helpful, understanding and trusted, or who are models, children will venture out into the unknown, and will tackle what doesn't come easily. I hope to show this with many examples, but the story of Dan will perhaps be the most dramatic.

The reader will see in this book, I think, evidence that the lives of these children were made richer, their horizons were extended, and their skills were developed. But it was not because Allen and I had a programme which we taught effectively. Indeed the pages of this book are littered with examples of me interfering with children's learning by being too teacherly. No, they learnt most when they brought their imaginations and intelligence and past experiences to bear on school activities. In important ways, Allen and I took our lead from the children themselves. They were our focus and our starting point.

And so, in this book, I'm wanting to share with the reader my perceptions of these particular children; of Anna and her fluctuating feelings about herself; of Chris and his growing self-confidence and understanding of the wider world around him; of Dan and his nightmarish battle with reading and writing; of Kate and her developing friendship with Zoe as they made the turtle; of Paul and his impact on the group and on his friends. I'm wanting, too, to share the excitement of the medieval village, a project that grew in all sorts of unexpected ways. And I want to write about my own feelings and thoughts during this time, of how it sometimes felt like we were travelling in a deep and exciting forest, with mists suddenly closing in and then clearing again, the well-worn paths all leading backwards, and just a few dim tracks winding off through the darkness ahead.

To write the book I have drawn on four sources - the diaries I kept during the period; transcripts of interviews with children and adults who took part in the village; my memory; and (when these sources failed to supply details of situations or dialogue) my imagination. I have tried in all this to capture the personalities of the people involved and the atmosphere of the actual events.

The AME School is a non-denominational, independent school in Canberra which was founded some fourteen years ago by a group of parents who called themselves the Association for Modern Education (AME), and who wanted something different for their children. Exactly how it was to be different has been the subject of debate within the school for all of its life, though there's always been an emphasis on close and informal relationships between teachers and pupils, and an attempt to make the classrooms lively and happy places. There are usually between 200 and 250 children at the school, and they range in age from five to sixteen. The pupils come mainly from middle-class homes, with many parents working in Canberra's government departments. The AME staff are appointed by the School Council, which oversees all aspects of the running of the school, and which is made up primarily of parents, though teachers are represented. The day-to-day happenings in the classrooms are the responsibility of the teachers.

Working with children in unorthodox ways was not easy, as the reader will discover, even in as supportive a climate as we enjoyed at the AME School. Since leaving there, I have been teaching in the government system, working in overcrowded classrooms, large schools and amidst government cutbacks. There is a temptation to be overwhelmed, or to fall back on the values and apparent certainties of a traditional school system. It seems to me that the times demand a more imaginative response.

Many friends and colleagues read early drafts of the book, and helped me shape it into its present form -Margaret Byrne, Liz Rawlins, Beth Basnett, Allen Rooney, Peter Scherer, Bernie Perrett, my father Mick (who also found me the perfect hideaway for writing) and Enid Shann. And I found the imagination and insight of Michael O'Rourke of McPhee Gribble Publishers bracing, challenging and deeply helpful.

I want to acknowledge, too, the debt I owe to some of the many writers on education. I found that the books of A.S. Neill, John Holt, George Dennison, Charles Silberman, David Holbrook and R.F. Mackenzie (to name a few) spoke directly and excitingly about children.

Molly Steinberg helped me with the typing, photocopying and transcribing of many hours of recorded interviews. My sister Cathy, her husband Peter, my mother Betty, and Patrick Prouheze helped in many practical ways while I was closeted away finishing the book.

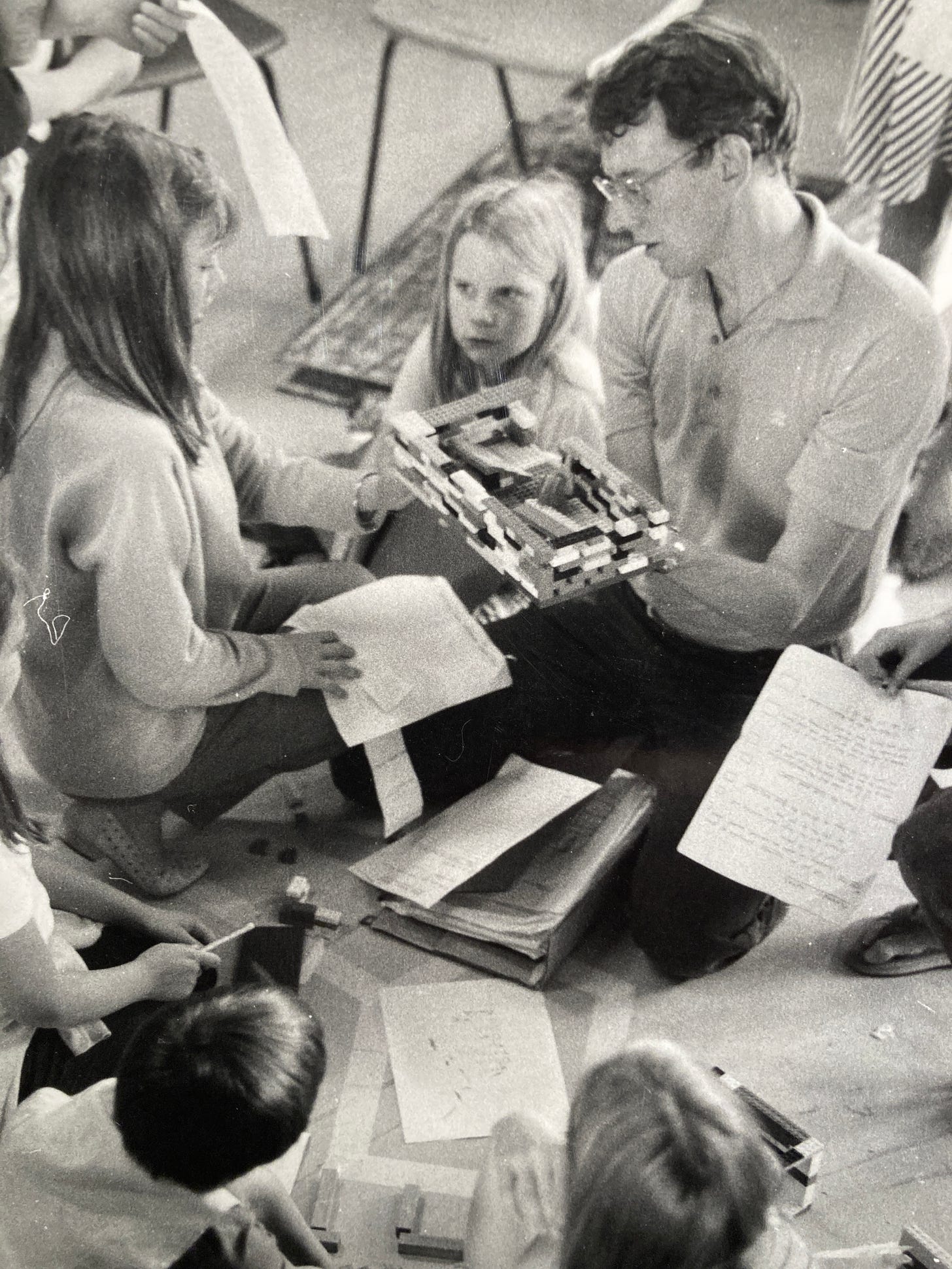

Liz Rawlins and Allen Rooney took the photographs which appear in the book, and which do so much to capture the atmosphere of the village.

The children themselves - Chris, Anna, Paul, Dan, Kate and her friend Zoe - were tremendously helpful, as were their parents.

I owe a more general debt of gratitude to the AME community: to the parents for their faith, to the staff and Bernie Perrett, the Principal, for their help and insight, and to all the kids for their energy and enthusiasm.

And working with Allen Rooney for a little more than three years was a real joy. His thoughtfulness, sensitivity and lovely sense of fun helped me through the times when I couldn't see the way out of the forest, and made the good times especially good.