Part 1 Chapter 6: Interlude

From my book 'School Portrait' (McPhee Gribble/Penguin, 1987)

I was met before school one morning towards the end of 1983 by Christine, a woman in her late thirties who had been, for several weeks now, a student-teacher in our classroom. Christine had spent the years since university at home with her young family, and was now looking forward to starting a career. She had an air of calm efficiency about her, and a ready smile. She clearly enjoyed being with children, and was particularly popular with the younger girls, who would vie with each other to sit on her lap during meeting times.

There was an older man waiting with Christine. He was in his forties, and had the thick compact moustache one usually associates with British army officers. Walter was Christine's supervisor from the teachers' college, and had come to watch one of her prepared lessons. As we stood chatting, he seemed at pains to appear quite comfortable amidst the bustle and noise of our classroom, though he held his clipboard tightly under one arm, and was tapping his biro against it as his eyes flitted round the room.

Christine had chosen to give a lesson on the history of early Canberra, and, as usual, she had prepared thoroughly for it. She had some photos of Limestone Plains when the only existing buildings were some farms and a church, and she passed these out the beginning of the session to the ten or so eleven-year-olds in our quiet room. She also had a letter written by one of the early settlers in the area, describing the language and the effects of a drought on the farmers. She read the letter out loud, asked the kids what they could deduce about early Canberra from it, and the children answered dutifully. Then Christine gave each child a list of questions about the letter and photos, and for twenty minutes the children wrote quietly.

I'd observed many student-teachers giving prepared lessons like these, and I could remember giving a few of them myself. Christine's lesson was more successful than most, because she had selected her material and planned the session carefully. But, as the kids answered questions like, ‘What kinds of transport are mentioned in the letter?' and ‘What evidence is there in the photos that religion played an important part in the lives of Canberra's early settlers?', I couldn't help but compare the scene in the room with the one in the cubby area which I could see out of the window. Allen was sorting the timber into large outdoor shelves, and about a dozen kids were banging in nails, helping each other to carry large planks, and digging post holes. One group had recently finished building a two-storied cubby, mainly out of old packing crates, and Mark was standing on its roof, acting the part of the king in the castle. In another part of the area, a cubby had been flooded out by rain the night before, and its owners were on their knees in the mud, bailing out the dirty water with jars from our wet area.

Which of these two activities provided the children with the deeper insight into the lives of the early settlers, I wondered rhetorically. The cubby building, with its boundary disputes, timber and tools shortages, the kids' pride of ownership, and the minor natural disasters? Or the classroom lesson, where the kids were writing simplistic and lifeless answers about churches and carts?

Walter was very pleased with the session, he told us after the kids had gone. It had been thoroughly prepared, its aims and objectives clearly spelled out, its presentation effective and disciplined. There had been a balance between teacher-presentation and pupil-participation, and between oral and written work. After Christine had left us, I asked Walter what he thought the kids might have learned from the session. ‘Some appreciation of the settlers early life, and valuable practice in the basic skills of discussing and writing,' he said.

The following morning I had an appointment with a parent. Tony was an ex-journalist, now based at home writing a book. He was worried about his son, Stuart, who'd always been a reluctant reader, and was concerned that not enough was being done at school to help. He and some other parents had been discussing their mutual concerns, and were thinking of approaching the school Council with some definite proposals, which, he’d told me over the phone earlier in the week, he wanted to discuss with me.

I told him about yesterday's lesson on early settlers, and about the contrast I'd observed between the cubby area and Christine's classroom.

'Are you saying, Steve,' he said, as we sat on some logs not far from the cubby area itself, 'that you think kids should be allowed to spend all their time in the cubby area if they want to? How would they learn to read and write? When would they do any maths?'

‘No, I don't think they should be able to spend all their time there,' I said. I told him that I thought there were useful classroom activities which some of them wouldn't come to unless we insisted. I liked kids to include some reading and writing and number work in their contracts, though, as much as possible, what they did in these areas was up to them. It was just that our education system had got the balance all wrong. It saw the cubby building and children's play as supplements to the basic 3-R's schooling, whereas for me it was the playing, exploring, imagining, questioning, and creating which was basic.

‘Take yesterday's lesson, for example,' I said. ‘If it had been based on the experiences those kids had had in the cubby area, on their negotiations, building, disappointments and triumphs, then a session organised by Christine about the early settlers could have been just the thing to stimulate an interest in history, to set the kids looking more closely around a museum or dipping into some old newspapers or history books. But, presented the way it was, the lesson made no attempt to link the material with the outside lives of these children. And the children behaved in that lesson accordingly, as if the subject matter, while possibly mildly interesting, didn't have anything to do with themselves, their thoughts or their experiences.'

I told Tony the story of the desert dweller who left his tribe one day, and travelled beyond the known boundaries of his world. After many miles, he arrived at the banks of a mighty river. He'd seen water before of course, when the occasional rains left impermanent and muddy water holes, or when he dug up roots to sqeeze out their moisture. But this river was something new, and he knelt before it in wonder. He tasted the cool, fresh water, and watched a small branch being whisked along by the river's power. He saw the light play over the rapids, and gazed at the peaceful reflections of sky and hills in the deeper pools. What a beautiful thing this was! How wonderful to capture some of it, and take it back to his tribe! So he scooped up some of the river in a bark bowl, and carefully carried it home. But, when he came to show his water to the rest of his tribe, it had died. It did not flow or splash or swirl anymore, it had no strength, and soon it turned stagnant. The tribesman cursed the water, and threw it away.

‘When we take children out of the world of their own experiences,' I said to Tony, 'out of the world of fantasy, imagination, talk, activity, argument and play, then we remove them from the source of their energy and intelligence. They then appear either dutiful and somehow limited, as in Christine's lesson, or bored and rebellious. We need to base what we do at school on what really matters to kids.’

Tony couldn't see how school activities could be organised around what happened to be occupying the minds of the kids at any given time. 'By the time you've surveyed the kids' current preoccupations and planned your work around them, the children's interests have changed.'

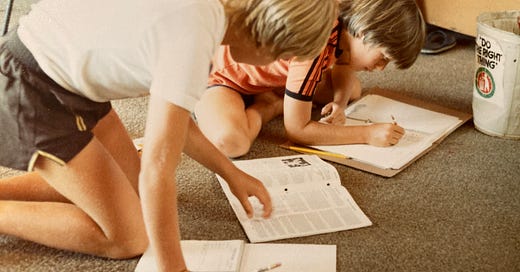

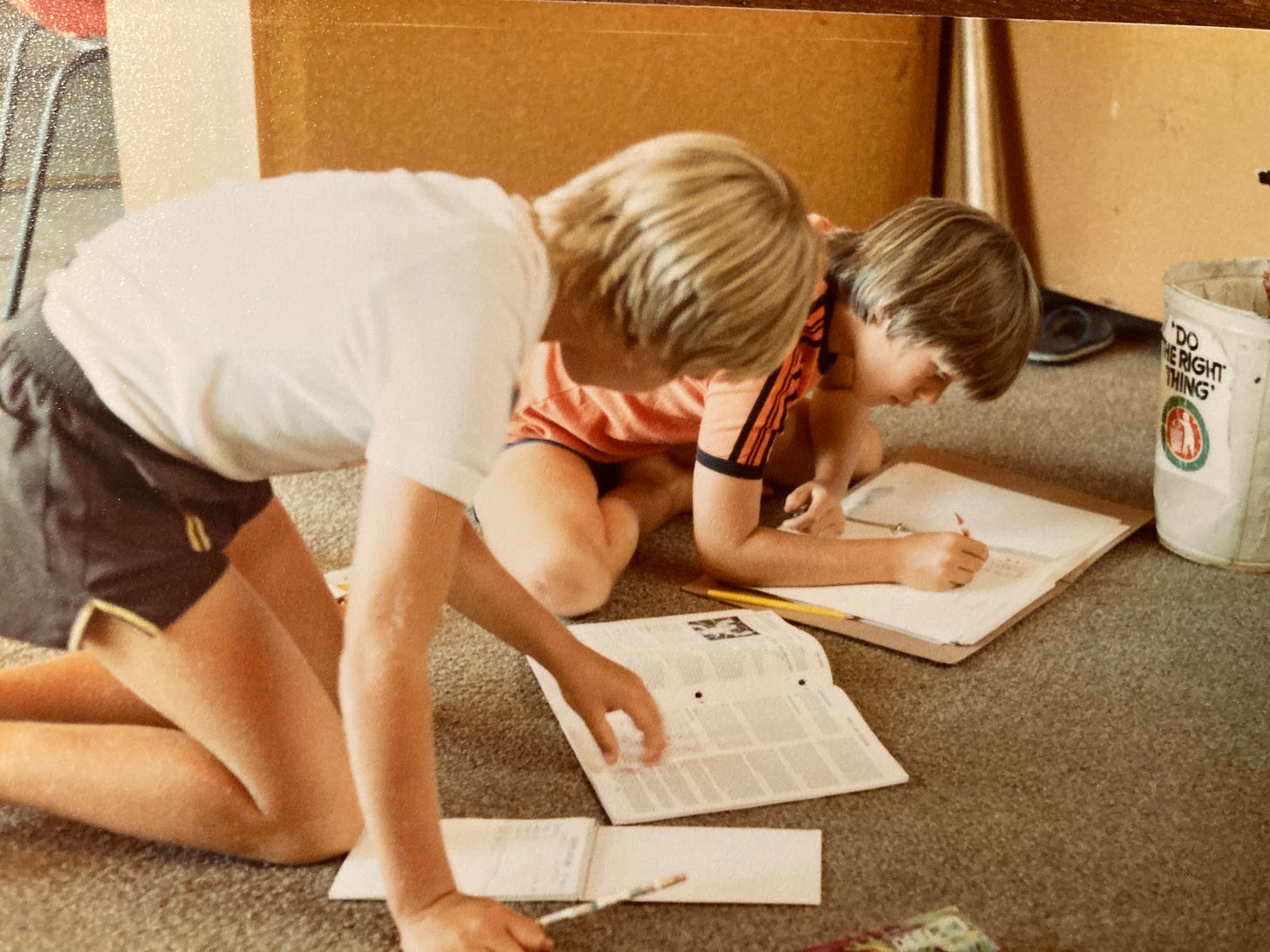

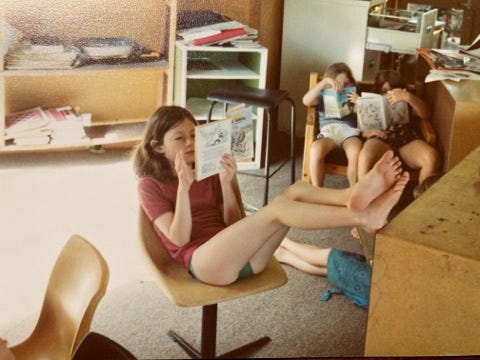

'That's true,' I said. ‘Which is why there needs to be more time in the school day when the adults aren't organising lessons themselves, when the kids have a chance to pursue activities they choose, in ways which they determine.' I described how Allen and I knew that kids would want to have time to play and make things with friends. We knew that many of them would want to draw and write and paint. That they'd enjoy stories and making up plays, that they'd want to go on camps and day trips, that thost of them would browse in the library. These are all activities they do if they're given the chance, so we give them the time, space, materials and encouragement.'

‘It sounds wonderful, but frankly I don't see it working,’ said Tony. ‘I like being in your classroom. I like the friendly atmosphere, and I like the relaxed look on my son's face when he's here and when he's ready to go off to school in the morning.' But it seemed to Tony that his son was missing out on some basic instruction in reading and writing. His son wouldn't browse in the library, not unless he was forced. 'Stuart feels he's a weak reader, and he says he can never think of anything to write, so he doesn't. That's going to get worse unless you teachers start making him do some work. When the organisation is as loose as you have it here, with kids all working in different places, doing different activities, then some are going to slip through the net.'

"Well, that happens in every kind of school,' I said. There was no school system in the world where a teacher was expected to work with twenty-five or more children that could guarantee to reach all the children, even when the school had as its sole aim the teaching of 'the basics'. I'd worked in exclusive private schools in Sydney and Melbourne, in comprehensive schools near Bristol and in Aberdeen in the U.K., and in government primary and high schools in Canberra. In every one of those schools there had been kids like Stuart. It didn't matter how the children were taught, or what proportion of the overall programme was devoted to the development of these skills. It was natural that Tony wanted us to fix the problem up, to find the quick remedy. But there was no magic, instant solution.

"So what are you saying, Steve? That we all relax and have fun, and wait till Stuart learns to read and write by himself? That sounds pretty irresponsible to me.'

‘No, we don't just wait around. We try to make Stuart's life here at school as full as possible, we try to make room in the day for him to build in the woodshed and make models in the wet area, both of which he loves doing. We show him that we value these things by talking to him about them, asking him to show what he makes to the group, and asking him for suggestions about what materials we need for these areas. We also plan bigger events, based on the outdoors or on make-believe and role-play, which we think will stimulate him. And we make time for him to tackle the skills he finds difficult.'

It all seemed too haphazard to Tony. Why, he wanted to know, had we gone for six weeks in 1983 working on a large-scale play, during which time the only reading and writing Stuart had done was incidental? He didn't see why we couldn't put aside a small part of each day to give kids like Stuart the regular practice they needed. ‘These other activities you do here are fine, and I don't want them interfered with,’ he said with he some feeling. 'All I want - and I'm speaking here for a number of other parents - is that you pay more specific attention to some basic skills, that you have targets for language and maths skills, that you regularly assess each child's progress in relation to these targets, and that you keep us informed about this progress. Then at least we'll be in a better position to help our kids get over these difficulties.'

Tony went on to tell me that he and about ten other parents of children in the primary school had framed these requests in the form of resolutions, which they were going to present to the School Council.

Knowing that a group of parents was about to petition the School Council for changes in our classroom practice stimulated in me a considerable amount of soul-searching over the last months of 1983. Was it possible to isolate these literacy and numeracy skills, and to teach them in a more orderly and effective way than we had been doing? Would Dan have learned to read any quicker, or Anna become less intimidated by numbers, in a classroom with specific targets and regular assessments?

There is, I think, beneath the surface of all teachers who work in alternative ways, a fear that perhaps we're making an awful mistake, that we're sacrificing what might be mundane and routine and basic for what is immediately exciting, stimulating and creative. We do our work from day to day, buoyed up by the kids own excitement, but in a world that is telling us we're wrong, were frivolous, we're idealists with no sense of what life is really like. And underneath there's the worry that someone will be able to prove that our theories are wrong, that kids who are taught by us are disadvantaged.

The issues raised by Tony brought about this fear in me. It brought it out into the open, and over the following months I worried away at it. The more I thought about it, the more I felt I needed to tackle it head on. It seemed increasingly clear to me that what the parents were asking for - the targets, the assessments, the regularity - were not just added extras that we could tack onto our existing programme. They were a fundamentally different way of looking at children and learning.

They were based on the assumption that children are only learning to read when they have a book in front of them, only learning to write when there is a pen in their hands, only learning to compute when they are doing a sum. I could see, by watching my own kids at home and by working with these kids at school, that children make sense of the world (a world that includes words and numbers) through play, through pretending to be shopkeepers or cooks or librarians or monsters or Darth Vader, through cooking, through arguing, through coping with their day-to-day lives, and through the stories they make up and hear. They watch what other people do, and they copy and adapt. They explore and experiment with material objects, and with words and numbers. This is how they become literate and numerate.

I wanted the children in my class to develop all of the skills that were basic to living in our modern society. I wanted to see children come to know themselves well, to understand something of their motivations, their potential, their strengths and limitations. I wanted to see them become more knowledgeable about how societies work and how they could be influenced and changed. I wanted to see some of the children becoming leaders or innovators. I wanted them to be able to think clearly and creatively, and to be skilled in communicating their feelings, thoughts and opinions clearly, both for themselves and for others.

I wanted to see the children becoming more aware that others had thoughts, feelings and rights, and that 'consensus' wasn't just a political slogan. I wanted to see them develop the skills and knowledge that enable people to find out about the social, intellectual and physical world around them.

My aim was to encourage the development of these skills through helping children to explore the world which they found around them, rather than forcing them to explore what we adults deemed important. It seemed to work better that way, and as a result the children became more literate, more numerate, more skilled. And I'd learnt, from working with children like Anna, Chris, Paul and Dan, that every child takes a quite unique and uneven path to social, emotional and intellectual maturity, and that this was incompatible with the parents' call for order and predictability.

Tony and the other ten parents presented their resolutions to the School Council, and there followed a period of debate within the school. A parent working group was set up to talk to parents and teachers, and to report back to the Council in 1984. And, in the meantime, Allen and I had started to talk about having a medieval village project in our classroom.

My talk with Tony had crystallised a lot of my thinking, and I began to feel a kind of responsibility to 'put my money where my mouth was', to somehow clearly demonstrate my principles. It was in this frame of mind that I began my planning for the village with Allen. There was a part of me that saw the project - with its emphasis on the make-believe, fantasy, role-play - as a testing ground for the ideas that I'd been putting to Tony.

There were potential problems in this. I was in danger of setting myself up, feeling that I was putting my reputation on the line, giving myself all sorts of self-imposed standards and pressures. The village project could end up being more important to me than to the kids, more centred around my need to prove a point than the kids' needs to explore the world around them. It was a danger that I was only vaguely aware of at the time.