Part 1 Chapter 4: Dan

From my book 'School Portrait' (McPhee Gribble/Penguin, 1987)

It was 9.30 on that first morning of 1982. The kids had arrived, and it was time to start. I wished Allen luck with his first day as he closed the divider that separated our two rooms.

'OK, everyone, time to get started,' I called out to the kids in my class. 'Could we sit in a circle on the carpet by the windows, please?'

The kids made their way in their twos and threes to the spot I'd pointed to. I could sense them watching me out of the corners of their eyes, looking for hints as to what I was like. There was some small talk in the circle for a few minutes, and then I began.

‘Can you all think for a minute about what it is that you'd really like to do, or to learn, this year? If I know what you're expecting from being in this group, well, that's going to help me with my planning.'

Some of the kids looked thoughtful, others looked a bit taken aback, as though I were invading their privacy. There were a couple of nervous giggles, and someone (Chris?) said under his breath, 'Doing no work!'

We started around the group.

‘Ice-skating,' said the first girl. ‘I’d really like us to go ice-skating some time.'

I smiled and nodded, even though this wasn't the sort of response I'd had in mind.

'Roller-skating,' said the second.

'Horse-riding,' said a third. I was resigned, by now, to a fairly superficial list of 'fun' activities. Oh well, I thought, my fault. I should have explained myself better, or done it in a different way.

‘What about you, Dan?' I asked a boy with fine brown hair and a chorister's cherub face.

He didn't hesitate. 'I really want to learn how to read and write this year.'

The room was suddenly very still. Dan's comment was so unexpected, so unlike the comments of the three before him, that it was as though he had said something embarrassing. Given the circumstances, I thought that to open himself up as Dan had done took a fair degree of courage. Or was it desperation?

We continued around the circle, but I found myself listening with only a part of my mind. I had first laid eyes on Dan one day in Katherine's class when I'd been invited through to watch some small plays. Dan sat under a table with an embarrassed and stubborn grin on his face, even though he was meant to be in one of the plays. Katherine couldn't coax him out, nor could his friends.

At the end of 1981, Katherine and I had gone together to meet someone at a reading clinic who had been helping Dan with his reading. Dan's mother had been there too, and had cried as she described to us the nightmare that learning to read had been for Dan.

I hoped very much that I could help him. But how? From what Katherine had told me about his reading, his problems seemed enormous, much greater than any I had so far encountered. I had no special training, nor had I found the 'specialist' at the clinic very helpful. She'd done a series of tests, and had given us impressive-sounding analyses of auditory and oral skills, short and long term memory, general knowledge and intelligence. But they didn't tell me anything about the person called Dan. And they didn't tell me what to do to help him with his reading.

The discussion around the circle led on to other topics about what the kids had done last year, about activities they'd seen my class involved in, and about some of my plans for the coming year. I was involved in it all, but conscious at the back of my mind of the responsibility I felt towards Dan.

Later I talked about Dan with Penny and Nancy, two other teachers at the school with whom I lunched regularly. They both had a particular interest in reading difficulties, and Penny had taken a year long course on the subject in London.

I described to them how that morning I'd asked Dan if he'd like to read to me, and how he'd immediately looked both anxious and determined. He chose a particularly easy book, one with a short sentence and a big picture on each page, which he'd managed quite well. But I could tell from the way his eyes darted back and forth that he was using the pictures as much as the letters to work out the simple text.

Penny and Nancy agreed on what would be most important for Dan. Firstly, they told me, he needed to have books around him which he could read easily, no matter how simple, so that he would be picking up skills and confidence just through the act of reading. And secondly I needed to take every opportunity to bolster his morale, through the inevitable ups and downs that he would encounter as he struggled with a world saturated with print.

What I liked especially about those meetings with Penny and Nancy was the lack of jargon, the practicality, the fact that I went away feeling more empowered rather than somehow inadequate in the face of the knowledge of the 'experts'. I left these lunchtime meetings convinced that there were in fact no experts in this field, just a lot of people struggling to understand and help real children with very real problems.

I saw a much more confident and lively Dan that afternoon when he and his good friend Michael worked in the wet area with some of our recycled junk.

"Hey, let's make a sewerage works,’ said Dan, picking out some cardboard toilet roll cylinders. ‘These can be our pipes!’

They consructed a rough sewage works in about fifteen minutes, laughing and chatting happily as they worked. Then they got some empty egg cartons and made a boat and four barges joined together with a string cable.

Katherine had told me that Dan had painstakingly kept a diary in 1981, and that it was important to him. So, after he and Michael had put away the models, I suggested that he begin a new diary for this year. Do you want to write about your models?" I asked.

‘No,’ he said, shaking his head very definitely. ‘No, something else....I know, I'll write about the roll.' I had asked him earlier in the day if he would help me keep the roll.

He worked much more seriously on this writing than many of the more literate kids, his head bent over the page except when he was asking me to spell nine of the thirteen words. It took him about fifteen minutes to write, in a very neat and angular print:

I am looking after Steve's roll, and Steve has to fill it in. 8/2/82.

The following morning, I gave out some spelling exercises for the bulk of the class, and then worked for a while with Ra and Dan. I gave each a transcript of a simple story I'd recorded on tape, and I asked them to listen to the recording and follow the transcript. After some practice, and when they felt ready, they were to come and read the transcript to me.

But it didn't work out like that. Both wanted my continuous attention, but other kids in the class were needing help too. Ra became discouraged, and he told me that he couldn't find the story on the tape. I found that for him. Later he returned to complain that he couldn't read the transcript. I explained again that it was a transcript of what was on the tape, and that he could use the two together. Then he came back because 'it was too noisy in the room'. Dan was with him this time, looking rather anxious.

I cleared some kids out of the quiet room for them, but soon Ra was back, saying that he didn't like the story and he didn't want to do this anymore. I was feeling frazzled by now, and worried that the activity seemed to be damaging morale rather than helping them with their reading. Ra went off to the woodshed, while I went into the quiet room to see how Dan was feeling.

He looked up from the transcript as I walked in. His eyes were glassy.

'Do you want to go and do something else?' I asked. 'Ra's finding this too difficult, and he's gone off to the woodshed.’

Dan nodded, and left. But I didn't like the way it had ended, and at lunchtime, I sat with him outside for about ten minutes.

"How's it all going?' I asked, as we sat down.

'Good, he said, but his eyes avoided my face. I sensed that he’d feel more comfortable listening, rather than talking about his feelings, as he seemed to feel ashamed of his difficulties.

‘I've been thinking about what you said on the first day,' I said, ‘about wanting to learn to read and write this year. And I've been talking to Penny and Nancy, who have both had lots of experience with kids who've found reading hard, just like you. We all agree that it's most important that you read and read and read. It doesn't matter what you read, as long as it's reasonably interesting, and it's easy enough. It's no good struggling with books that are too hard to enjoy or understand. That's what was behind the tape-recorder idea, but exactly how you do this reading isn't all that important. You can read books silently to yourself and then come and show me what you've read. Or you can read them out loud to me. Or we can use the tape-recorder like we did today. Lots of different ways. What do you think?'

He'd been listening intently to me, and had regained some of his composure. 'I think I prefer the idea of you reading into the tape-recorder,' he said.

'OK, I said. 'Let's start that way, and we'll do that till you feel you want a change. How about going inside now and choosing a book that you'd like me to read?' Dan chose a book called The Black Pirates, one of a series of early readers, and I recorded it that night. When arrived the following morning, Dan was standing at the reading corner, flicking through a book of ghost stories.

‘Steve, do you think you could record one of these for me?' I looked through the book.

'I will if you like,' I said doubtfully. 'But I think you would find it too difficult.' I flicked through the pages as I spoke. ‘Here's a short poem about ghosts,’ I said. "How about I record this one?"

'Could you read it to me?'

‘From ghoulies and ghosties and long-leggity beasties And things that go bump in the night, Good Lord, deliver us!'

‘Hey, Michael, come and listen to this!' he called, and I read it again. "It sounds really good, doesn't it?'

‘It's an old prayer from Cornwall,’ I told them. ‘People in the olden days used to ask God to protect them from the things that made creepy sounds at night.'

He was clearly excited by the poem, and so I recorded it for him on the spot. He took the recording and both the ghost and pirate books to a quiet corner, and read through them several times.

The next day I asked him if he'd like to read to Barbara, the school counsellor who was in the classroom for the morning.

‘Yeah, fine,' he said. ‘But I couldn't be bothered with the tape. I'll just read the book'. He read very confidently, Barbara later told me, obviously knowing much of it by heart. And he kept reciting bits of the poem at odd times during the day, including at one of our group meetings.

One morning a week or so later, Allen and I decided that our room was looking dull and uninspiring. So I brought in some clay, and a whole lot of useable junk, and Allen put some brightly coloured paper squares out, set up paint and papier-mâché, and got some kids to help him make some storage areas. We'd borrowed a push-mower to cut our grass outside, and there were digging tools available. We put some of the kids' paintings up around the walls, and displayed their models on our open shelves.

As the kids arrived that morning, we could see them responding to the altered environment.

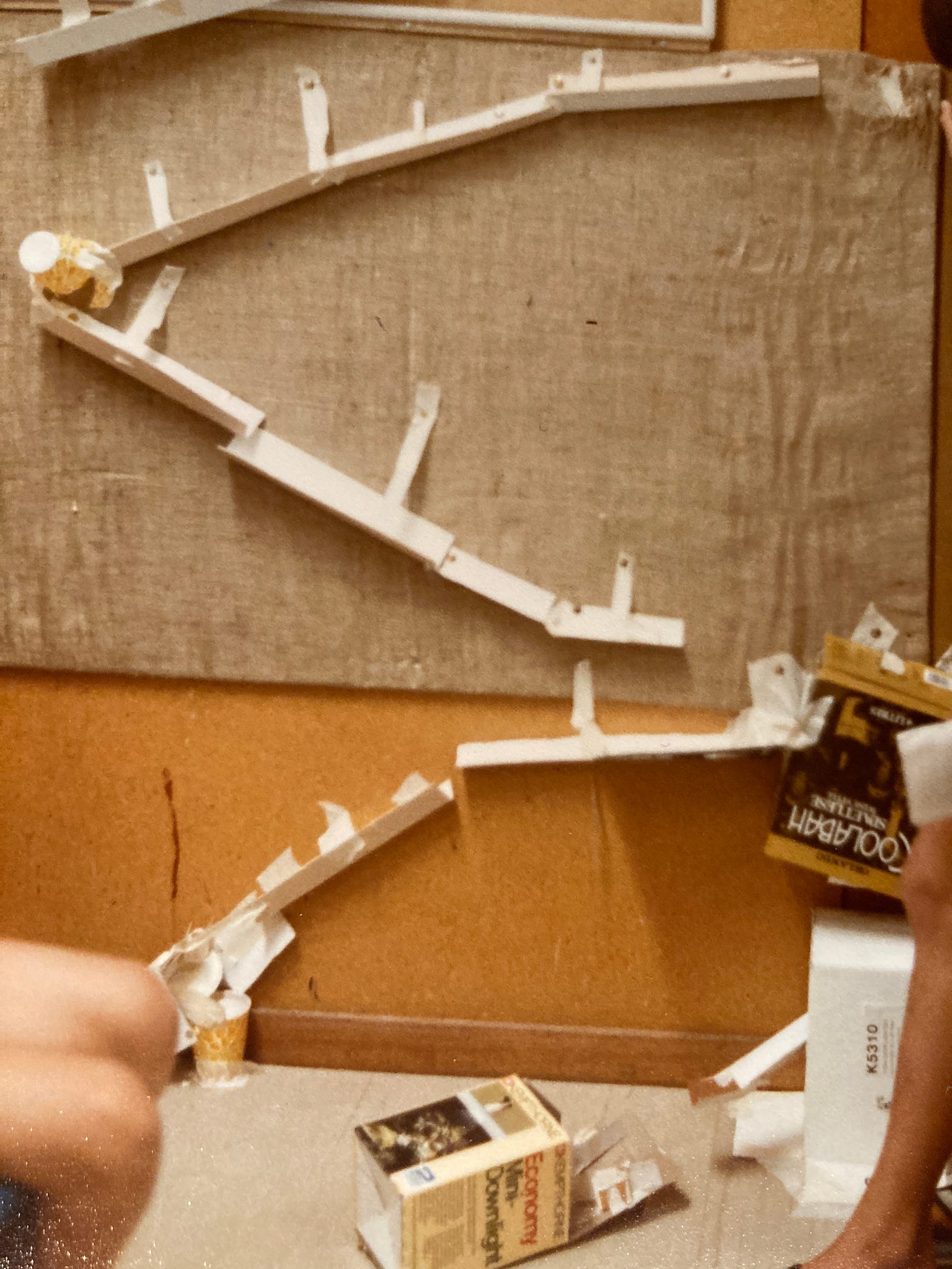

Michael and Dan couldn't wait to get to the junk table, and they were soon joined by Chris. I was outside for most of the morning, gardening, but every time I poked my head in, they were absorbed, constructing a large-scale marble chute. Dan called me in just before lunch, to show me what he and the others had been doing.

"Watch this, Steve,' he said, and he released a marble at the top of the chute.

The marble hung for a second, as if deciding whether or not to make the trip, then gathered some speed and disappeared down a toilet-roll tunnel. The track flattened out somewhere inside the tunnel, so, when the marble emerged again, it was travelling quite slowly. It came to a junction, and the boys exclaimed as it took a route it hadn't taken before, and plunged down a steep slope towards a 'spinner' - a star-shaped piece of cardboard, fastened in the centre with a pin so that, when the marble brushed past it, it started spinning, its bright colours blurring and merging.

Through more tunnels and along more tracks it ran, gathering speed until it came to a sharp upward slope like a ski jump, where it looped through the air and splashed into a jar half full of water.

The boys cheered.

I called Allen over, and we watched it again. Then, just before morning tea, we called an impromptu meeting of both groups and everyone sat round and watched the marble go through its paces. Chris had taken over and was doing the commentary for the big group. Michael and Dan were standing next to the chute, looking very proud and pleased.

As I looked at Dan's beaming face, I thought again of the importance of our valuing the things he did well. We'd given him the time to make the marble shute, we'd supplied some materials, and we'd organised a meeting where he and his friends could show their work off. If the day was dominated by activities based on reading and writing, kids like Dan would inevitably see themselves as failing. I hoped that, more and more, Dan would come to see his difficulties with reading and writing as specific areas needing special work and help, rather than as a bigger problem that somehow reflected on his general intelligence or capability.

We did some more tape-recording that afternoon, and Dan was in a relaxed and happy frame of mind. He brought me a book called The Little Blue Sea Horse, which had a fairly childish story but which didn't embarrass him. We sat in a quiet corner of the room while everyone else worked on their spelling, and he crouched beside me as I read.

Hey just a minute,' he said suddenly, and I turned off the tape-recorder.

He went to the wet area sink, and brought back a glass and a spoon.

OK,' he said. 'Can you start again?'

I began again, and every time we came to the end of a page (he was following the text as I read), he would clink the glass with the spoon.

'It will help me know where it's up to later if I get lost when I’m reading it on my own,’ he told me. It was good to hear that he was taking this activity on and making it his own, rather than it mechanically doing what I suggested.

Dan, do you want to come outside and read to me now?' I asked the following morning.

He was working on the marble machine with Chris and Michael, and he looked tense and hesitant when I spoke. The spark that I'd seen in his eyes the day before was missing. Was he feeling his friendship with Michael threatened by Chris's presence, I wondered.

He followed me to the bench outside. It was warm and still out there, and I'd been gardening with Jessie and Cass. I'd looked into the room earlier, and had seen Dan in a corner by himself, with the book and the tape recorder, concentrating hard on what my voice was reading, following it with his finger and his lips.

‘I only want to read a little bit,' he said, looking at the ground. He was almost sullen.

He managed the first page, and then came to the sentence, The ship sailed away across the sea.

‘The ship... sailed ... sailed …across ...’

His finger stopped at the word 'across'. He'd already read the word 'away' as 'across', and he was confused. I decided to let him try to figure it out, as he did when he was feeling confident.

‘The ship sailed across ...'

Suddenly he began to swing his legs vigorously and rhythmically, and then to kick at the ground. I looked quickly at his face. Tears were streaming down his cheeks.

'Oh, Dan, it's OK. What's the matter?' I put my arm around his shoulders.

"Is it to do with something that's happened inside, with Michael or Chris?' He shook his head.

"Shall we do a bit more?' I asked. He nodded, and opened the book again. I helped him with the sentence that had caused the problem, but then he came to the word 'west' and stumbled over it. The tears welled up again.

I didn't want him to leave feeling like that, so I talked to him for a few minutes.

‘I don't know why you're feeling like this today, but I can see that it wasn't a good idea for us to read together. If you're feeling bad about the reading, I want to say that you've been doing really well over the past week, and I've really enjoyed working with you and listening to you read. You shouldn't be upset over stumbling like that - it's a small thing, and you've been doing very well.'

He didn't say anything, just brushed away the tears with the back of his hand. He opened the book again.

‘Is this where I was up to?' I nodded.

He read a couple more pages, with me helping at any hint of a difficulty. My arm was still round his shoulders, but as soon as he'd regained his composure he pushed my hand away. Then he went off, back to the marble chute. When I walked through the room about fifteen minutes later, Michael was drawing something and Dan was sitting next to him, watching what Michael was doing, his chin resting on Michael's shoulder.

At the end of the day after the kids had gone home, I went to talk to Penny. I described everything that had happened that morning, and asked her what she thought.

‘Well,' she said, 'maybe there was something bugging him that had nothing to do with the reading. But my guess would be that he was just too tired to read out loud to you. It's an enormous effort for kids like Dan to read - much harder than we can imagine.'

She’d once been to a lecture on reading difficulties, she told me, where the lecturer had written some 'words' in an unfamiliar script on the board, and had then made the class try to read what he'd written, suggesting that it was really obvious and logical and he couldn't see why they were having such difficulty. The panic induced by the feeling that she couldn't see the obvious made the task even more difficult, and she felt exhausted after only ten minutes.

'It's something like that for kids like Dan when they read,' she told me. ‘The rest of the world is telling them that it's obvious, it's logical, and can't understand why they're having such difficulty, which only makes it worse. And don't forget that he'd already been reading to himself for some time. That part of his brain was probably very, very tired. Reading to you on top of that was just too much.'

What Penny said sounded right. And added to all of that, I thought, would be the resentment Dan must feel when he looks around the classroom and sees how easily most of the other kids read. It must seem very unjust to him that what Michael has taken to almost naturally has been, for him, fraught with confusion.

I was away from school one day soon afterwards, and Robyn, Allen's wife, took the group for the day. She read a story about a dragon, and then asked if anyone wanted to do some painting based on the story. Chris and Dan decided to paint together, and when I arrived at school the following day, Dan was already in the classroom.

'Hi, Steve,' he said. 'Do you want to have a look at what Chris and I did yesterday?'

He pointed to their painting on the wall. The dragon dominated it, with geometric patterns down its back, and a long red tail, bumping and bounding along (as the story described it) with pretty coloured smoke coming out of its head'.

He and Chris spent time that morning on a second painting, this time of the dragon chasing some people down a hill. They chatted happily to each other, recalling details of the story as they painted. We hung them side by side on the wall, and showed them to the whole group later that day.

Afterwards he and Michael collected leaves, twigs and grass and used them to make an abstract collage. Again, it was Dan who came to get me to show me what they had done.

‘Hey, that's lovely!' I said. 'Something you might like to experiment with some time is combining some painting and collage - doing both in the one picture.’

Dan's eyes lit up.

‘We could maybe paint the sky and a sunset onto this one,' he said.

He looked quickly at Michael, but Michael didn't seem so keen.

'But not right now,' said Dan. ‘We're going out to do some weeding in the flower garden.'

I caught up with them about twenty minutes later. They'd found some flowers in amongst all the weeds, and they called me over to ask what they were. They had plans to make borders for the garden, and again I noticed how thoughtfully Dan was listening to my suggestions.

He was such an easy kid to like. During this second month of the term we had a couple of particularly good reading times together - he wanted to read, he read well, and he went away feeling rather proud. I could see it in his walk. I felt that he was learning something about the shape of particular words and about the sounds of letter combinations, not through any special language exercises, but from experiences he was picking up from the reading itself.

But not everything went well. One morning after the kids had been working on their own activities for about half an hour, a rather dejected-looking Dan came out from the woodshed, where he'd been making a model boat with Tobias.

"My boat broke,' he said. His bottom lip trembled. He looked very young and vulnerable.

'Can it be fixed?' I asked. 'Let's have a look.' He handed it to me, and looked on in silence as I turned the boat over in my hands. The mast had snapped in two.

"Show it to Allen,' I suggested. ‘I'm sure he'll know how you might fix it.'

‘I don't really feel like doing any more on it. I'm a bit sick of it.'

‘Well,' I said, 'what do you feel like doing?'

'Don't know really.' He looked at his feet as he spoke.

I guessed he needed some quiet time to himself. Ra had just come back from the hill behind the school, where he'd been looking for insects under rocks, so I suggested that Dan do the same.

"OK,' he said, and he went off with a jar. But he was back fifteen minutes later, empty-handed and still despondent.

Later that afternoon, with a lack of sensitivity (given his discouraged mood that morning) which in hindsight I find embarrassing, I asked him to read to me and I explained to him that I wanted to give him a reading test, not to assess his reading (which I'd felt I'd been doing all along as we worked together), but to give us a kind of measure against which we could chart his progress. 'I'll give you the same test at the end of the year,' I told him, 'and we can see how you cope with it then.’

Each page' of the test had a question on it, and I asked Dan to read the question out loud and then tell me the answer.

‘ Can a dog run?' he read. ‘Yes, a dog can run... Does a cat have ... legs? Yes.. Does a cup… have a …’

The word was lid, but Dan couldn't get it. He sound out the ‘l’, but couldn't think of anything that would make sense. He started to cry.

It's OK, Dan,' I said.

‘I feel so frustrated,' he said between sobs. ‘I'm just so frustrated.'

‘I know how you feel, Dan. You'll make it, really you will. You're so keen and you try so hard. It'll come in the end. I've worked with kids who've had these frustrations before, and I know it comes after a while.' I felt I needed to confront directly what was so clearly on his mind. 'There's nothing wrong with you. I guess sometimes you feel there is. You're not dumb. It's just going to take time, and lots of reading.'

As I talked, Dan's sobs became quieter. He listened, but he didn't say anything.

'Do you want to go on, or leave it there?" I asked.

'I don't know,' he said quietly.

‘I think it would be fine if you wanted to go now.'

Dan dried his eyes, and went off.

‘Our quest is to go on a long adventure, and to kill a dragon and get the gold. This is where we start,' said Dan dramatically, partly to the audience of one (me), and partly to Tobias, who had been working on the play with him for a couple of hours now. They had taken over our quiet room, and had turned it into a fantasy world of caves, deadly worms, cardboard dragon and treasure.

I'd already asked Dan if he wanted to show his play to the whole group, and he'd been very definite that he only wanted to show it to me. Tobias had looked a bit disappointed.

'OK,’ he said to Tobias, 'off we go, through the underground tunnel!'

Dan gave me a running commentary as they crawled their way under a line of chairs.

"This is the Tunnel of Worms,' said Dan. 'We have to go through it to get to the treasure, for our quest. The worms are deadly - one bite and we've had it!'

They came to a piece of string dangling down through the chairs, and Tobias pulled on it. There were about ten cardboard worms attached to the string, and they came cascading down onto the boys' backs.

‘The worms, the worms!' cried Tobias, and they struggled and gasped and thrashed around under the chairs. Cardboard worms were flung out at regular intervals, accompanied by grunts and shouts and cries of ‘Take that! ... I strike with my dagger! … Look out! There's one on your back!'

They survived the worms, and inched their way forward. Goblins attacked at the tunnel's exit, but they were quickly dispatched, and the heroes found themselves face to face with the dragon, a cardboard box with eyes and teeth drawn in red paint.

‘There's the dreaded dragon," said Dan. 'Draw your sword, and let's fight to the death.'

They fell upon the box, Tobias stabbing it and Dan hopping around and shouting, ‘Die! Kill him! Death!' Tobias fell back, panting. The dragon was done for.

Now,' said Dan, 'where's the gold? Ah, here it is!'

He bent down and scooped up handfuls of yellow paper scraps, and stuffed them into his pocket. Tobias knelt beside him, and did the same.

‘Now we must destroy the magic diamond,' said Dan. I couldn't make out whether he had made this up on the spot or whether it was a part of the original plot. Whatever it was, Dan swung his sword through the air at some imaginary target. ‘There!' he said. ‘Now we must find our way home. Our mission is complete.' They crawled back through the chairs to safety. Tobias looked rather breathless, Dan very pleased.

"That was great,' I said. 'Very exciting! Where did you get the ideas for it?'

‘Sort of from our heads, and sort of from Dungeons and Dragons,’ said Dan, referring to his favourite game. He often spent time flicking through Dungeons and Dragons manuals, looking at the pictures and getting friends to read bits to him. He played occasionally too, and, whenever I'd watched, he was always very, very quiet, and on the edge of the group. Not nearly as lively and animated as I'd just seen him.

That afternoon he wrote:

I am doing a play about D and D (Dungeons and Dragons) and it is fun. 3/3/82.

School, it seemed to me, must be a very mixed sort of place for him. On the one hand it provided him with all sorts of stimulus and opportunity - his friendship with Michael, the stories he heard and loved, the painting and model-making, the play with Tobias, the opportunity to get through the reading barrier in what I hoped was a friendly and understanding relationship with me.

But it was also the place where he was brought face to face with the fact that he couldn't read like others could, and he knew how important reading was in our society.

'Steve, how do you spell "Chris" and "turn" and "orange"?' Dan whispered.

He handed me a scrap piece of paper, and I wrote the words down. We were sitting in the dining room at Jervis Bay, on our third day there. All the kids were writing. Some parents who'd come to help us on the trip were buttering bread and putting fruit and drink into the esky for a picnic lunch at Summercloud Bay, and Barry was writing on the blackboard.

A few minutes later, Dan came up and showed me his writing.

I saw a cuttlefish and I thought it was seaweed and me and Chris saw the cuttlefish turn orange. 10/3/82.

Yes, I thought, he'd had a good day yesterday. In fact he'd been enjoying himself ever since we left the school, playing cards on the bus, excitedly exploring the rainforest with the other boys, plunging his head into Tianjara Creek to cool down, setting the crab lines in the pouring rain at night, finding a frog and sketching it, pushing his friends off a rubber tyre at Greenpatch, snorkling, building the dams and rivers at Black's Harbour with Michael and Chris, finding an octopus with Barry, prawning by the light of the moon.

‘What should I do now?' he asked.

‘Well, we're going on a walk, and we'll end up at Summercloud Beach for a picnic,’ I said. 'Barry's written on the board a list of the things you need to put in your backpack. I'll read them to you, if you like, and then you can go and get ready.'

"Do you think I could try reading them myself? You listen, and help me if I can't do it.'

We looked up at the board together and I noticed how he was working out meaning from the context, using the sounds of letters to help him guess the word.

'Drink bottle … ss … socks …ff … flippers … suntan cream … hat …’

We'd had the same sort of list up there every morning, so there was a fair bit that Dan could predict. Nevertheless he read the whole list with almost no help from me, and I felt that small incidents like this must be boosting his confidence, giving him the feeling that he was coping with reading tasks in the real world.

The next morning, Dan wrote for much longer. Again, he asked me to spell most of the words for him. When he'd finished, he showed me this:

I saw lots of big sea urchins, and I did not see any small sea urchins and sea urchins are prickly and you can find the sea urchin shell on the beach 11/3/82.

It was the longest piece of writing he'd ever done.

Back at school, I stood in front of the class, talking about the projects the kids were about to start.

‘There were once two children, Alfonso and Cordelia …’

‘Oh god,' Chris groaned, 'not another one of Steve's stories!'

‘What's this got to do with Jervis Bay?' asked someone else.

‘There were once two kids,' I repeated, ‘and both went on a trip to the coast with their school and had a ripper of a time. They climbed sand dunes and explored rockpools, went walking through the bush at night and heard sounds they'd never heard before. When they got back to school, they were asked to do a project on something connected with the trip.

'Alfonso went to the library, found a book on sea creatures, and decided to do a project on the octopus, not because he was specially interested or because he wanted to find out more about the octopus, but because he had lots of information on it.

‘Cordelia, on the other hand, had been wondering for some time about, on that blood-curdling scream she had heard while walking one night. She had in her mind all sorts of pictures of what might have happened to the animal that screamed. So she spent her project time finding out about night predators and the prey. She also did a series of paintings showing several gruesome scenes of the bush at night, and wrote a short story to go with the paintings.

'The moral of my story ...'

'It had to come,' said Chris, ‘here we go again.'

‘… The moral of my story is that we want you to choose a subject that really interests you, and we want you to think carefully about how you're going to pursue that interest. You can just use books and write answers to questions if you really want to, but perhaps some of you will want to be more adventurous, more creative, like Cordelia was ...'

As my voice droned on, I became conscious of Dan's face in front of me. He was looking up intently, as though he were struggling to understand exactly what I was saying. I knew that he'd spent the weekend with his family at the coast, and he looked very tired. But I also knew that he would be fighting his inclination to doze off, and would be trying hard to do the right thing.

I finished my monologue, and then Allen asked those who'd already decided on a project to share their ideas with the rest of the group. Then everyone went off to write a rough plan for their project, which they would then hand in to one of us.

Dan sat by himself at a table, looking through a book on rockpools.

'Any thoughts about what you're going to do?' I asked.

‘Not really, he said. ‘I’m just looking through this book to see if I get any ideas.'

Dan had talked animatedly at the coast of several possibilities for his follow-up work - the cuttlefish, the frog that he'd sketched, the crabs we'd caught. But he was looking somehow deflated now, and I didn't think it would help if I pushed him to some commitment.

The following morning he still hadn't decided, but he overheard me planning to make a large model rockpool with Michael, Jenny and Jenna. He asked if he could join us, and that morning he helped the group construct a wooden frame for the model, which we covered with chicken wire and then papier-mâché. It became the focus of Dan's day for most of the following fortnight, as we prepared our Jervis Bay display for the parents.

We took time off one morning to do some reading together.

He brought over a book from the Pirate series, but was looking distinctly unenthusiastic about reading it. As it was the first time in about a fortnight that he'd read to me, I thought it important to go carefully. So we looked at the pictures and talked about what the story might be about, and then I asked Dan if he'd like to read it to me.

"Well,' he said, ‘it looks interesting. But I reckon it might be too hard for me to read.’

‘Would you rather try an easier one then?'

‘The trouble with the easy ones is that the stories are boring. Nothing ever happens. They're sort of for little kids.'

‘Well, if you like, I could read this one to you, and then you could maybe go and choose an easier one to read to yourself. What do you think?'

'Yeah, that's a good idea,' said Dan. 'That sounds good.' He was chatting quite easily now, and I was pleased we had taken the time to approach the actual reading gradually and gently.

I started reading, and sensed almost straight away that not only was Dan enjoying the story, but he was following the text with his eyes. I slowed down, running my finger under the words as I read them, and he started to read out loud with me. I asked if he'd like to read every second page, which he did with my help whenever he hesitated, and we continued like this until we'd finished the book. It was one of the best reading times we'd had together, I thought as he took the book back. But it was so hard fitting these sessions in with so much else going on.

I watched Dan playing with the papier-mâché paste one morning, at a time when he was clearing away the mess before going to lunch.

'Hey, Michael,’ he called. 'Look, I'm washing my hands in the glue!'

His hands were covered in the stuff, and he was slowly turning them over to give his hands an even spread.

'It's really warm and gooey,’ Dan said. "You ought to try it!'

"That's silly,' said Jenna. ‘It's just going to stick all over your hands.'

‘Yes, I know. That's the idea. I like it when it dries, I like peeling it all off. Good fun!'

Later Dan and Michael rigged up an electric light in the bottom of the rock pool, and covered it with green and blue cellophane:

Then they darkened the room so that the light threw colour and shadows around the pool.

But he hadn't been especially stimulated by the project, and he hadn't looked particularly happy over the fortnight, despite our successful reading session and his occasional enthusiasms with the model. He reluctantly dictated the following to Katherine when she visited our classroom one day.

Me and Michael and Jenny and Jenna made a rockpool and it was boring. I started it because I wanted to start a rockpool.

We got the wood. We nailed it together. We went up to the garage to get the wire. We put the wire in a pool shape and then we started papier-mâchéing.

Jenna made a crab and stuck it onto a ledge.

Then Michael made the best ledge out of papier-mâché. Then Michael and me went and got some wood and papier-mâchéd it - it was the best ledge.

Then I came up with the idea of having milk cartons for ledges.

We had a reading time together soon after the rockpool was finished, and he read a simple book fluently.

‘That was very good,' I said. 'How are you feeling at the moment about your reading?'

'A bit good and a bit bad,' he said, without enthusiasm.

"You've been looking a bit down in the dumps recently, I've felt.'

'Have I?' he said, his voice dull and his eyes avoiding mine.

‘You haven’t felt that?’ I didn’t want to probe, as he was clearly uncomfortable, but I did want to give him a chance to talk if he needed to.

Not really,' he said. And we left it at that.

I worried that somehow the way we'd organised the classroom since the Jervis Bay trip had contributed to Dan's lethargy. Did he feel his reading frustrations all the more because he could see other kids around him looking up information in books and writing up their research? Had I killed off the interest in sea creatures that he had so clearly shown while we were at Jervis Bay?

I found time over the following days, as our routine returned to something like it had been at the beginning of the year, to work with Dan on his reading again. One morning, I said to Dan and Ra that I wanted to do some spelling with them.

'Us?' he said. 'But we don't do spelling usually. You said you thought it wouldn't be right for us.'

‘Well, I've got something just for you two today?

Dan looked very pleased to be joining the big league. Doing spelling seemed to be something of a status symbol.

I brought over some of the cards that Penny had given me at the beginning of the year, each card with a simple word on it, like "hat', 'hit', 'hot', 'hut', 'bet', 'but', 'bat' and so on. We spread them out, and sorted them into piles - 'a' vowels in one pile, 'e' vowels in the next, etc. Then I read the words out, and we played a game of keeping the card if you could read the word. Both had a lot of difficulty distinguishing between the different vowel sounds.

(I discovered, from playing with these cards and others often over the coming months, that it wasn't simply a matter of ‘teaching' the sounds to Dan and Ra and then having them able to use this 'knowledge' in their reading. Their memories for symbols and sounds were very weak, though both could remember what they'd done at the coast or details from a story I'd read months ago. I came to feel that they learned to read better, more through their general reading than through this kind of exercise.)

After we'd played the game for about ten minutes, they went off to do some reading. Two minutes later they were back again, and Dan was holding a book in his hand.

‘Steve,’ he said, 'could we do some reading together, Ra and me? We've been looking at this book and I can read some of the words and he can read some of the others, so between us we reckon we could do it.'

‘Sounds like a great idea,’ I said, and off they went, and spent at least twenty minutes in a beanbag together, making their way happily through the book.

But I had a shock the next day. I was standing next to Dan in the reading corner when he picked up a book called A Ghost in the Classroom, and started to look through it.

‘That's funny, he said. This book looks harder to read than it did last year. Last year I could read this one easily, but this year it looks too hard. It's changed.'

I didn't know what to say. I looked through the book, and felt sure that he wouldn't have been able to read it at the beginning of the year. I felt thrown and worried. Maybe his improved reading had just been an illusion. Maybe he was just pretending more effectively!

I talked to Penny at lunchtime, and she told me that she was sure there was nothing to worry about, that the evidence of my own senses was reliable. But I felt an urgency about getting back to listening to him read more often. It was so important that he feel he was getting somewhere.

Dan returned to his daily writing in his diary, but it was still pretty much a limit of one sentence in about half an hour.

I played soccer at lunch and Andrew kicked the soccer ball into my stomach and it hurt and then Gerard tripped me. 13/4/82.

I couldn't put up my tent because it was missing something. 13/4/82.

Soon after this I wrote a report on Dan's progress to his parents, and asked for their thoughts about it all. Dan's mother wrote back:

Last Wednesday evening he was in tears when asked to write down the names of odours to be identified at Cubs. He said that he hadn't cried because he didn't know the smell name, but with the frustration at being unable to write. I am amazed that he persists with any effort to read and write. I can only believe that he must be receiving a lot of encouragement to persist from you. My own feelings range from helplessness through anger to despair

And so it continued, with the same ups and downs, over the following eighteen months. Dan continued to read regularly, more to himself now and less out loud to me, and he seemed to pass through some kind of barrier towards the end of 1982, when his reading of reasonably easy books suddenly became fluent. He still struggled with the unfamiliar, and still occasionally shed tears of frustration. But there was improvement.

He began to loosen up a little with his writing too, becoming less self-conscious about his spelling and prepared to write slightly longer pieces using his own spelling, which was erratic but (usually) readable. And, like Chris and Anna, he loved the big plays and Australian history, and he dictated to his mother a particularly good story about his character's life as a convict.

Like the others, he was again in my group in 1984, now as one of the older kids in a group of nine, ten and eleven year olds. Michael had moved to another group, and Dan and Chris had become good friends.

The bigger the group, the more comfortable Chris felt, but not so Dan. While Chris was announcing to the assembled group of forty-eight that I was sensitive about my long nose and elusive at clean-up time, Dan was sitting in a corner well out of the limelight. He was giggly and uneasy during the small group drama based on the story of Prometheus, and refused to perform with his group in front of the whole class. Later, he didn't feel able to choose any spelling words from a long list I gave him, and asked me to do it for him.

He was more relaxed the following morning. In fact I saw a side of him I hadn't been aware of before.

No don't go yet,' I said to Caitilin and Anna, who were already moving towards the clay in the wet area at the end of our class meeting. ‘I don't want anyone to move a muscle until we've sorted out what everyone's going to do.' Then I asked each kid in turn about his or her plans.

When I'd finished, everyone but Dan left. He was sitting rigid, with a twinkle in his eye.

‘What is it, Dan?' I asked. "What's going on here?' Almost without moving his tightened lips he said, 'You said not to move a muscle.' He laughed at my mock frustration, and then went to get his writing book.

At the end of the week, I wrote a couple of paragraphs about Dan for my records.

I was very impressed with how Dan tackled the maths with Chris, when many other kids were overwhelmed by the problem. Dan obviously did a lot of work on it at home that night, and came in the next day with pieces of paper covered with diagrams and sums.

He decided that he wanted me to write out his story (after he'd written what I thought was a very imaginative first sentence), and he spent a couple of sessions making a very attractive good copy. He didn't want to read it out to me at the end though, because he said, he doesn't like his stories. I believe that Dan undervalues his own ability as a maker of stories. (Remember last year's Australian history story!) He likes writing in his diary.

He wasn't pleased with his painting.

I showed Dan what I had written, hoping that he would recognize enough key words to be able to decipher its meaning.

He made sense of the first paragraph, he told me, but needed my help with the second. Then, at my request, he settled down to write his response.

He got as far as the first line, and I thought it was going well.

But, when I next looked, he had rubbed out what he had written.

He looked up at me as I sat next to him, the tears ready to spill from his big eyes.

‘I just can't do this, Steve. I can't do it.'

'Don't worry, Dan,' I said. T'll do it for you. You just tell me what to write.'

But he couldn't think of what to say, and sat there looking more and more miserable. Other kids kept coming up for help or to show me their work, and I felt myself being torn in two directions. We talked in a short-hand kind of way about his writing, and I reminded him again of the story he'd written the previous year.

In the end he simply wrote:

Steve got most of it right.

We had a parent evening soon afterwards, at which I showed parents some of the kids' work and my comments about it. I asked the parents to write something themselves, and Dan's mother wrote

Sometimes I feel like spiriting Dan off to some world where reading and writing and arithmetic don't exist.

There are lots of niches for adults without these skills - even in this advanced society.

After the parents had left that night, I sat for a while in the empty classroom. I'd talked to the parents in general terms about the connections between academic progress and creative expression, through the visual, dramatic and manual arts, and through writing. I'd said something, too, about trust and mutual respect between teachers and kids. Now, with the room empty, I thought of what these things meant for someone like Dan.

Without them - without the marble machines, the trips to Jervis Bay, the fantasy games in which he was a hero, the painting and playmaking, and without the quiet and unpressured reading times we'd had together - Dan's self-confidence would have remained low. What was important for the kids fortunate enough to be free of specific learning difficulties was vital for kids like Dan.

How would he fare in the village that we were planning, I wondered. Would his shyness in a crowd make him retreat? Would the hustle and bustle, the air of excitement, swamp him? Or would he find a little niche for himself, rather like the ones his mother hoped existed in the modern adult world for people like Dan?

There was no way of knowing. We'd soon see. I turned off the lights and went home.