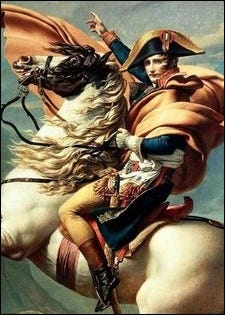

The teacher as Napoleon Bonaparte!

I've been reading an entertaining essay by Neil Postman called 'The educationist as painkiller'. He writes:

... there is nothing worse than ignorance on the subject of education. This is so because the subject of education claims dominion over the widest possible territory. It purports to tell us not only what intelligence is but how it may be nurtured; not only what is worthwhile knowledge but how it may be gained; not only what is the good life but how one may prepare for it. There is no other subject - not even philosophy itself - that casts so wide a net, and therefore no other subject that requires of its professors so much genius and wisdom.

(p85 of Postman Conscientious Objections)

It's not just the professors who feel the pressure of this burden; it's us classroom teachers as well. We're meant to be experts in subject matter that is beyond the expertise of any human mind. We can try to understand intelligence, worthwhile knowledge and the necessary preparation for the good life; indeed, we can spend most of our careers attempting to match our classroom practices with our fuzzy and evolving answers to these big questions. But we always end up feeling that there's a gap between what we ought to know and our current understanding. If we try to be experts (or even knowledgeable) about these things, we end up feeling inadequate or even impotent.

Postman suggests, both playfully and seriously, that there's a solution to this problem:

The solution is to diminish the extent of our limitations by diminishing the scope of the subject. In so doing, we may increase not only our stature but also our competence and potency...

This, then, is the strategy I propose for educationists - that we abandon our vague, seemingly arrogant, and ultimately futile attempts to make children intelligent, and concentrate our attention on helping them avoid being stupid ... By changing the way we talk about our role as teachers, we provide ourselves with necessary constraints and realizable objectives ... The educationist should become an expert in stupidity and be able to prescribe specific procedures for avoiding it. (pp6-87)

A sense of humility, a sense of potency, a specific subject matter. This is precisely what doctors and lawyers have, and this is what is to be gained if educationists adopt the metaphor of educationist as painkiller. (p89)

*****

Like so much of Postman's writing, the essay is funny and wise at the same time. It's well worth a read to enjoy what he has to say about how teachers might go about reducing stupidity. But here I don't want to go down that track. Instead I want to try a Postman-inspired experiment as part of the little research project I'm working on. Over my previous half dozen or so posts, I've been reporting on conversations with 16 years old Josh, and have been trying to come up with maxims or principles that might guide literacy teaching. But I've been feeling that there's something not-quite-right about these maxims. They feel sound but not all that useful; interesting but of limited value as a guide to action. A bit vague. A bit impotent. What would happen, I wondered, if (following Postman) I were to turn these maxims on their heads? Instead of focusing on promoting literacy, focus on fighting illiteracy? Waging war rather than establishing peace? (I'm noticing how I'm drawn to a military analogy rather than a medical one. Interesting. I don't see myself as the fighting type!) This experiment might be a dead-end. But that's the nature of research, isn't it: trying different things in order to see what works? There are many failed experiments in good science. So here goes.

*****

First of all, here are the six maxims for literacy teaching I've come up with so far:

1. The more I can infect my class with my love for the subject, the more individuals in the class will want to read. Maxim 1: Reading is fertilised by a teacher’s love for the subject matter.

2. The more my students know about the subject, the more they will want to read, and the more they will understand from their reading. Maxim 2: Prior knowledge is a gateway to reading proficiency.

3. The more the class inquiry is centred around clearly identified fertile questions, the more purposeful and effective the reading will be. Maxim 3: An inquiring mind directs a reading that is purposeful.

4. The more each student feels he can make a meaningful contribution to the learning of the class as a whole, the better he’ll read. Maxim 4: We read better when we sense we are agents in the learning of others.

5. The atmosphere in the class - the sense in which it is experienced as a community of scholars - will impact on the amount of good reading done. Maxim 5: Belonging, community and literacy are linked.

6. Teacher enthusiasm, fertile questions, prior knowledge, active learning and an animated community aren’t always enough. Maxim 6: Some academic texts need close and disciplined guidance.

Given what emerged from the last conversation I had with Josh when he talked so well about film and the part it has played in stimulating his thinking about Othello, evil and human nature, I would now want to add a seventh:

7. Literacy is about our ability to use texts (all kinds of texts, not just written ones) to increase our understanding. Maxim 7: Our work with written texts should not be isolated from our work with other kinds of texts.

They do have something of the ring of Create a wholesome literary classroom rather than Attack ignorance and lethargy. The first sounds bland; the second rather exciting.

****

So I want to have a crack at re-thinking these maxims as if they were battle guidelines for a military leader rather than part of a training manual for doctors or teachers.

Here's what I've come up with.

Let your love of the cause invigorate your army. (Replacing: Reading is fertilised by a teacher’s love for the subject matter.)

Wage war against ignorance. (Prior knowledge is a gateway to reading proficiency.)

Give the troops an objective; let them invent ways of achieving it. (An inquiring mind directs a reading that is purposeful.)

Order the troops to work as a unit. (We read better when we sense we are agents in the learning of others.)

Instill pride in belonging to the regiment. (Belonging, community and literacy are linked.)

Make sure the troops know their weapons. (Some academic texts need close and disciplined guidance.)

In battle, every object is a potential weapon. (Our work with written texts should not be isolated from our work with other kinds of texts.)

****

So where has this got me?

Certainly since writing this I keep remembering times when, with an enemy in my sights and a battleplan in my hand, I've felt more animated and potent. I wrote about one of these occasions in Play the game!

But does the narrative and metaphor we inhabit, and the language that we consequently use - have any effect on our effectiveness? Am I getting closer to some useful guidelines about how to approach the teaching of reading across the curriculum? Or am I being distracted by Postman's clever essay and heading down a blind alley?

I'd be interested in your thoughts.