Fear, drive my feet: managing my own pre-course anxiety

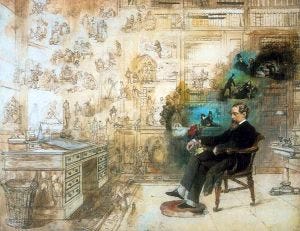

I’m standing in front of a class of secondary students, sensing their restlessness and desperately trying to hold their attention. I’m pulling out every trick I’ve learned: cajoling one sub-group, trying to beguile a second with a story or an interesting fact, and threatening a third. But I feel weak and dreadfully underprepared; I don’t really know the content or where the lesson should be heading, and I can sense the students seeing through my bluff and bluster. They’re about to walk out, I’m convinced, or give up, or maybe even riot. I redouble my efforts, but I can see that I’m losing them and that nothing will rescue this hopeless situation.

[My dream last week.]

I’m now nearly 65 and have been working with students for over 40 years now. I’ve loved teaching and the academic job I’ve got at the moment.

Yet I still have anxious nightmares before the beginning of every teaching year.

This underlying anxiety used to feel neurotic. Why would I have these dreams unless, underneath the surface, I felt insecure and unstable? I’ve come to think more recently that the dreams are healthy and help motivate me so that I prepare well. Because it’s fear rather than logic that’s driving my feet, my anxiety dreams trigger a process that is idiosyncratic and, in its early stages, not as immediately productive as it might be!

I can illustrate this by describing the five stages – familiar to me now – that I’ll go through between now and early February, when I meet the 200 students doing my Teacher Education unit on managing classroom behaviour.

Stage 1: Collecting resources

The logical place to begin would be to think about the purpose of the unit. What am I trying to achieve?

But that’s not where my underlying anxiety takes me.

Instead, with a kind of unconscious desperation, I collect my resources, scores of them, as if the more resources I have to throw at the students, the more prepared I’ll feel. I’m a bit like the warrior my son creates in his online game Skyrem. Before he goes into battle with an unknown enemy, he first gathers together an ebony dagger, an orcish battle axe, a dwarvish sword, full battle dress (including an invisibility shield) and various spells and potions. The more he collects, the more confident he feels. I’ve taught this unit before, so I’ve already collected a fair few weapons. I revisited them this morning, and, like the pre-battle soldier polishing his weapons, I made a mindmap of them, trying (unsuccessfully) to resist the urge to keep adding to them as I went.

2. Imagining the resistances

The relief from my anxiety which this manic collecting affords is temporary.

After making this mindmap this morning, I began to imagine characters, some of my future students, responding to the resources very much like the students in my nightmares.

I could see (for example) Janine, the student whose hard work and ability to play the game had got her top marks, being angry at the lack of guidance, at the assumption that she would have the time to wade through the resources and make independent decisions about which were relevant to her and which were not.

I could see Greg, the practical down-to-earth student who had already decided that university learning was unconnected with the real world, and that he’d learn the job once he got into a classroom rather than by wading through an old man’s reading list.

I could imagine conscientious Elizabeth, full of zeal and idealism about a new teaching career, quickly becoming overwhelmed with the mountain of stuff being thrown at her.

And finally I could see Allan, happy to take seriously anything which immediately appealed to him as being interesting or useful, but more interested in talking about teaching than in reading about it. What would I say to them? How would I keep them engaged?

Stage 3 Revisiting the aims of the unit

I hate Learning Outcomes and include them in my unit outlines only because they are compulsory. Here are the official Learning Outcomes for the unit I’m about to teach.

The spectre of the four resistant students forces me to think about purpose. What am I wanting to achieve in our 10 short weeks together?

I understand the thinking behind Learning Outcomes (make the purpose explicit so students know what’s expected), but always find them lifeless and limiting, like trying to package a mystery in a formula. In this case I find them particularly useless because these Learning Outcomes spring out of a view about teaching as performance that tells only part of the story. Clear verbal and non-verbal directions and generic practical approaches and strategies are important, but they’re a fraction of what I’d want this unit to be about.

Here’s my list:

Tolerating complexity: I want the students to know that there isn’t a single box of tricks, or a failsafe method of classroom management. There are different approaches that work with different teachers, different students and in different contexts.

Embracing critical analysis and self-reflexivity: I want the students to examine their own assumptions about what works. The research says that many young teachers, once they get into the classroom, quickly revert to teaching styles that are familiar to them, based on the teaching styles of their former teachers and parents, and that these often result in the repetition of ineffective teaching practices. I want my students to understand and critically examine what comes naturally to them, and to begin the work of shaping a teacher-identity that is both authentic and effective. I want them to think about what they want to achieve in their classrooms. Is it just about control? How central is learning? What implications flow from what they value? What kind of a teacher do they aspire to be?

Thinking holistically: I want them to see the important links between pedagogy, content knowledge and classroom management, rather than see these as unconnected components which need individual and separate attention and skills.

Becoming creative and informed makers of meaning: I want them to notice the way our unit assumes that the learner (which is them!) is an active inquirer and meaning-maker rather than a passive recipient of the teacher’s wisdom and knowledge, and how this inquirer’s stance stimulates motivation and creativity … and then to reflect on what this means for the way they are going to run their classrooms. I want them to know that our profession requires this inquirer’s mentality for the whole of their professional lives.

Stage 4: Basing the unit around fertile questions

Yoram Harpaz suggests that our classrooms should become places of where communities of thinkers research fertile questions together. They define a fertile question as having six main characteristics:

Open - there are several different or competing answers.

Undermining - makes the learner question their basic assumptions.

Rich - cannot be answered without careful and lengthy research. Usually able to be broken into subsidiary questions.

Connected - relevant to the learners.

Charged - has an ethical dimension

Practical -is able to be researched given the available resources.

Here the work has been done for me, as last year our teaching team came up with the following fertile questions or Nine Provocations. These provocations form the basis of the teaching course within which my unit is situated.

What kind of a teacher do I want to be?

Will I be allowed to be the teacher I want to be?

To whom am I accountable?

Am I ready to teach?

Is teaching a profession or a trade?

What will students want and need from me?

Should we teach students or subjects?

To what extent is teaching an intellectual pursuit?

How will I control my students?

Once I get to this fourth stage of articulating the central research questions, I begin to feel some of the anxious impulse to do all the work beginning to dissipate. I no longer feel I need to understand all the material, have all the answers, or accumulate a mountain of resources; I’m going to be guiding a community of researchers, not force-feeding my students with my own knowledge and experience. It’s not that I imagine that there will be no moments of challenge or discomfort with Janine, Greg, Elizabeth or Allan. But I see my role more clearly now. The ground feels more secure.

Stage 5: Checking the alignment of assessment and objectives

Will my assessments give my students opportunities to show that they have tolerated complexity, embraced critical analysis and self-reflexivity, thought holistically, and become creative & informed makers of meaning? I think so. We’re asking them to explore some of the Nine Provocations and to share the results of their explorations with us, using a number of different media. We’re requiring them to build their understanding on their critical analyses of their own and others’ experience and assumptions, gleaned from conversations, course work and time spent in the classroom. There are no short answer questions, no single mandated texts that they must study and master: they’re to pursue the questions that matter to them and to map the way their thinking evolves as a result of their labours. My job, between now and the first class, is to make possible resources available, and to structure week-by-week events that will stimulate research and collaboration.

Perhaps, tonight, I’ll sleep more peacefully.