Fictional characters: just the author in fancy dress?

In a chapter called ‘Truth and culture’ in her book on Foucault, Clare O’Farrell writes

Foucault notes early on in his career, following Nietzsche, that the ‘fact’ is already an interpretation. In other words, his writings are based on elements which are already ‘fictions’, things that have already been selected, fabricated and organised in certain ways. There are no primary sources or even physical artefacts that one can accept without question. Everything is already a secondary source, an interpretation. (p84)

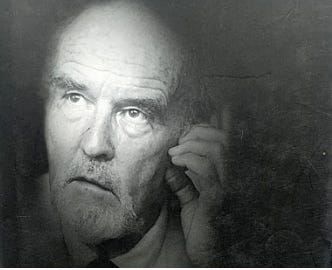

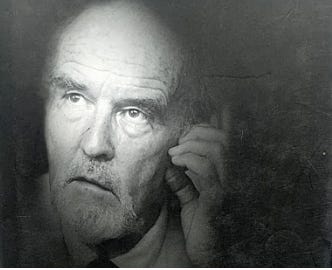

I was thinking about this as I drove down to Melbourne a couple of weeks ago, listening to a Late Night Live interview with Mark McKenna, the biographer of Manning Clark.

I’ve always loved the history writing of Manning Clark. Australian history came alive for me when I read his History of Australia. I felt the presence of real people in his accounts, whereas in other histories I’d been made to study at school and at university, there was something bloodless about the way the past was described. (I’m reading War and Peace at the moment, and am similarly thrilled by the way Tolstoy helps us understand that what happened in the past was experienced and shaped by people just like us.)

So I’ve never had much sympathy for Clark’s critics who have taken him to task for not having all his ‘facts’ right. It has seemed to me, as it apparently seemed to Foucault, that ‘everything is already a secondary source, an interpretation’. Clark’s history didn’t have to be always literally ‘true’ in order to be stimulating and important.

But when I got to Melbourne, I went online and read 'On reading Mark McKenna’s biography of Manning Clark', by Nick Gruen. Gruen makes the following claim:

But the ultimate shame is not that Manning got some facts wrong about his characters. Rather, the problem is that his archetypes – whether it is Alfred Deakin, John Curtin or Henry Lawson – never really expand into well-rounded characters who are uniquely themselves. The archetypes are a side of Manning in fancy dress. Hell in the heart, uproar in the trousers, wondering what went on in the mind of a woman, wondering what it was all for. Clark cannibalised the material for scenes that he could transform into stories he wanted to tell.

Gruen suggests that Clark’s characters are just versions of Clark himself, 'Manning in fancy dress'.

Is this what I do in some of my writing?

Last year I had an article published which began with a piece of fiction (based, I claimed, on a student and teacher I knew). Here are the opening paragraphs:

Alison sat in the pale green vinyl-covered 1970s armchair outside her lecturer’s office, drumming her fingers impatiently on the thin wooden arm rest. ‘This was such a stupid idea,’ she thought bitterly to herself. Everything about this was stupid. The decision to email Alec to ask for an appointment. The risky admission that she found the idea of having to write an essay terrifying. Allowing herself to feel vulnerable.

The door opened and Alec invited her in.

He was a portly man in his sixties, squinting, but not coldly, from behind thick glasses. The word around the campus was that he had an eye disease and was going blind. Certainly, in the one lecture they’d already had, it was clear that he couldn’t read the screen easily, and held his notes so close they almost touched his nose. Alison murmured an awkward ‘thanks for agreeing to see me’, then sat at the small round table opposite Alec.

‘How can I help?’ he asked.

I’m wanting to use this kind of fiction-based-on-what-I’ve-experienced-and-known more in my academic writing.

Perhaps, though, these characters just Steve in fancy dress. Would that matter, I wonder.