A mythopoetic methodology: storytelling as an act of scholarship

Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 2014,

Abstract

A pre-service teacher clashes with his mentor and the practicum ends badly. There is distress and a sense of failure all round. Questions get asked. Was the pre-service teacher simply unsuited to this demanding profession? Was the teacher education inadequate? Was the mentor a good fit? Were there the right kinds of support in place? Was the school culture intolerant of new ideas, new energies?

Given concerns about an ageing workforce, beginning teacher attrition rates and healthy work environments, questions such as these require thoughtful investigation. But the issues are complex. Complexity is not an easy thing to research.

The past hundred years has seen a number of significant attempts to understand personal and social complexity, from the grand structural narratives of the psychoanalytic movement through to post-structural accounts that pay increasing attention to the apparently chaotic interplay of intersecting life trajectories, shifting identities, and ordinary affects.

What methodologies nudge us deeper into perceived and experienced complexities? What ways of communicating the insights afforded by such methodologies are likely to have impact, to create affects?

In this paper, I suggest that a mythopoe

tic methodology (the writing of a story) plays a part in the scholarly attempt to see complexity more fully. I suggest, too, that a mythopoetic form (the telling of a story) has the potential to create useful affects.

The paper is performative rather than exclusively analytical.

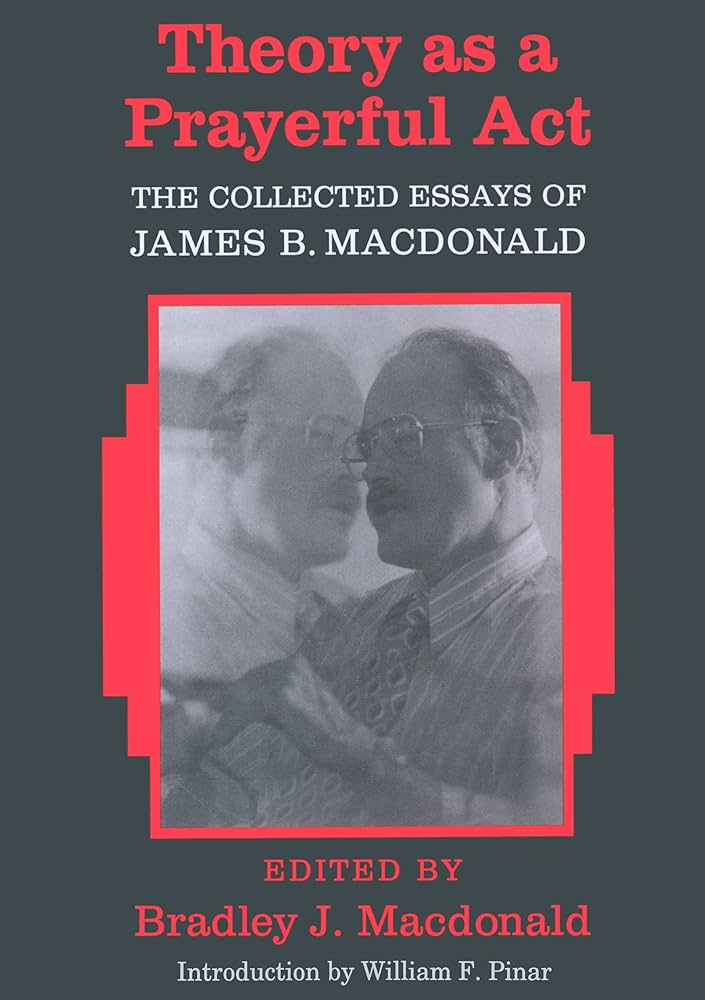

.. non-scientific curriculum theory is a mystery to most educators... It is a mystery because it deals with the mystery. (James Macdonald)

**********

1.

Shoulders hunched, hands thrust deep in his jacket pockets, Allan's eyes are watering as he paces, late at night, along a dimly lit suburban street. 'Fuck them, fuck them, fuck them,' he mutters as he walks. 'Fuck them all!'

He's angry with everyone and everything. It's all shit. It's all just bullshit.

He'd thought English teaching would suit him, what with his love of words, and with the satisfaction he'd got from his occasional tutoring work.

But from the moment he'd begun this first prac, things had started to go wrong. First there was that girl who, on his first day at the school, had made a fool of him in front of the class. Then there was the cold, unsympathetic, out-dated mentor he'd been saddled with. What were they thinking when they placed him with Susan? Didn't they care? Didn't they vet the mentor teachers?

Today's humiliation was the final straw. A lesson he'd put his heart and soul into preparing, and Susan had seen nothing good about it. Icily she'd questioned his motives; subtly she'd undermined his confidence.

Fuck her. Fuck them all.

He felt like pulling out. Maybe he should have taken the risk he'd once wanted to take, and tried to make a living as a writer.

Wrong decisions. Nightmare experiences.

Allan again blinked away the tears - they were now clearly tears - and strode on.

2.

Allan is an invention. I have had a number of students in my office telling me stories about their practicums. Most tell me how much they have benefitted from working with a mentor teacher and say that the weeks spent on prac were the highlight of their course. Some, like Allan, tell unhappier stories.

In 2012, after hearing a number of stories like Allan's, I decided to investigate further, not into the particulars of any individual case, but into the complex tensions and challenges of the practicum experience. I was especially interested in what might come to the surface if a small group of us attempted to write some educational fiction together. So, in September, I discussed the possibility with three of my former Graduate Diploma in Secondary Education students.

Why fiction?

The pragmatic reason was to protect the interests of students who had spoken freely to us about their experiences; we would create a fiction which, while informed by real experiences, transformed these into what Peter Clough (2002, p. 8) calls "symbolic equivalents."

The deeper motivation, however, was that we all suspected that the creation of imagined worlds was a valid way of discovering aspects of the real world inaccessible to more rational methodologies. The writing of a piece of fiction is an attempt to draw on intuition, imagination, and metaphor to see more deeply into an aspect of the experienced world. It involves wrestling with what emerges in order to put it through some kind of refiner's fire to test its authenticity. It is the methodology of the novelist and the poet. It is Proust coming to understand family, love, and memory; Tolstoy making sense of war; Rilke opening his eyes to the invisible and numinous. It is a methodology that directs attention to particular aspects of a studied phenomenon: its invisible underbelly, its ordinary affects (Stewart, 2007), its specificities.

So we wanted to write fiction in order to be able to say something about the nature of complexity.

There was, however, another reason for wanting to write a fictional story. We wanted our project to do something. We wanted our story to create an affect.

As a teacher (in schools and universities), I have a particular interest in the way a story creates affect in a reader or audience, very much like the "ordinary affects" that Kathleen Stewart describes.

A charge passes through the body and lingers for a little while as an irritation, confusion, judgment, thrill, or musing. However it strikes us, its significance jumps. Its visceral force keys a search to make sense of it, to incorporate it into an order of meaning. But it lives first as an actual charge immanent to acts and scenes - a relay. (Stewart, 2007, p. 39)

Anna Hickey-Moody (writing from a Spinozan-Deleuzian perspective) explains how affect is the imprint made on a body by another body (both bodies being assemblages made up of connections and flows and interruptions) rendering the impacted body more or less powerful in its ability to act.

A story is such an assemblage, or what Hickey-Moody (2013) calls a "bloc of sensation.”

A bloc of sensation is a compound of percepts and affects, a combination of shards of an imagined reality and the sensible forces that the materiality of this micro-cosmos produces’ (p. 94). Art... has the capacity to change people, cultures, politics. Art is pedagogical'. (p. 91)

The four of us wanted to create a "bloc of sensation," through a process that was itself affect-charged. We would swap stories with each other, share our writing, and allow memories and associations to be evoked by the words and subsequent exchanges.

First we talked together and wrote, the three beginning teachers about stories they had heard, and me about what seemed to be the emerging themes, trying as much as we could to stay with what Davies and Gannon (2006, p. 2) have called "an embodied sense of what happened": the bodily felt affects of the experience. I then produced a couple of tentative beginnings to a possible story, and we discussed the veracity of the emerging characters. There was a good deal of experimentation at this stage, with me drawing on my collaborators' writing to create characters and scenes, and my collaborators responding, reacting, suggesting possibilities.

Two characters - the pre-service teacher Allan, and his mentor Susan - emerged from this process.

We still had no plot for our story, and then I remembered an incident that had occurred some time ago and which (substantially fictionalised) might provide us with what we were seeking. I wrote a first draft, my colleagues responded, and an iterative process ensued which saw me producing multiple drafts before we were ready to show it to some valued and experienced outsiders. They, in tum, gave us further feedback, which informed the final version.

Our story is called "Both alike in dignity" (Shann, Edwards, Pittard, & Germantse, 2013), and its centrepiece is a lesson that Allan, on his first prac at Nullinga High School, gives to an English class. His task is to introduce Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, while his mentor, Susan, observes. Allan loves words and loves Shakespeare and he comes to the lesson with some optimism, despite previous behaviour problems with some of the students. He has a detailed and imaginative lesson plan, and, from his point of view, the lesson goes remarkably well. Susan, however, is critical after the students leave - she has a complicated life, other things on her mind, and has been somewhat put off by Allan's early ungrounded confidence. Allan is furious, and spends time that night writing a parody of the Romeo and Juliet Prologue, in which he gives vent to his outrage and which he posts on his private blog. Susan and the school are alerted to the existence of this blog entry, and Allan is summoned to the principal's office. He is told that he has breached professional ethics and that he has failed his prac. The story ends with Allan sitting outside the school at a bus stop, being awkwardly consoled by one of the students in his English class.

3.

Our project, as I have suggested, was partly an attempt to gain access to what might otherwise be invisible and possibly unconscious, and to contribute, therefore, to our understanding of complexity.

There are a number of traditions that form the foundations of this particular scholarly approach.

Psychoanalysis is one of them.

I was a psychotherapist for about 10 years, and so inhabited a world (through my training and practice, the writing of my PhD and the collaborations with my clinical and academic supervisors) that kept alerting me to forces, processes, and energies unfolding about which our conscious minds get only occasional hints.

Our unconscious mind, said Freud, is a three-tiered structure animated in large part by invisible and unconscious drives and instincts detectable in slips of the tongue, free associations, dreams, fantasies, and jokes. Our conscious mind, Jung added, is like a tiny island surrounded by the vast sea of an individual and collective unconscious, the latter composed of archetypal patters hinted at in dreams and fantasies and shaping life structures and stages, an idea picked up by Joseph Campbell (1949) and made popular in his idea of the Hero's Journey.

These ideas, Taylor (1989) and Ellenberger (1970) suggest, did not spring spontaneously into the heads of Freud, Jung, and their colleagues. The invisible - dreams, the will, vitality, hysteria, energy, animal magnetism, and other "vital forces" - was a major preoccupation with European philosophers, from Spinoza right through to Rousseau, Kant, Herder, Coleridge, Fichte, Schelling, Hegel, Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche. The psychoanalytic tradition was, in other words, just one aspect of a much larger cultural shift towards an interest in the invisible and the intra-psychic.

Humans, says the Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor, once had a much more animistic outward-turned consciousness; they felt connected to some source of meaning much bigger than, and external to, their individual selves; they felt bound to the earth, or spirit, to some great leader, God or to the gods. In order to know how to live a proper life, in order to orient themselves to the good, all that was required of humans was that they be guided by this external source. This animistic consciousness fostered a sense of interrelationship and connection: to the earth, each other, the community, the seasons, the land, animals, and so on.

But then something happened. The old certainties were "sponged away." It seems to have happened around the time of Nietzsche, though not because of him; Nietzsche was, in a sense, its messenger. As a consequence of this shift, our orientation has changed; we have been thrown back on our own resources, on a sense that we need to discover for ourselves an individual orientation to the good, a personal search for meaning. Because of this particular severing of the connection with a given external good, we have had to go inside ourselves, to find explanations for why we think and act as we do. Hence, there has been a growing interest in what might at work beneath the surface of our conscious minds.

Despite the postmodern turn (which has branched out along another path and to which I will return later), the idea that our thoughts and actions are shaped by unconscious drives, desires, and fears remains a powerful explanatory idea.

4.

Allan sits slumped in the counsellor's office. He's come because he can't concentrate on his uni assignment and needs a counsellor's note to get an extension. The counsellor suggests they talk. Why not, he thinks.

So, it's to do with your prac?' the counsellor asks.

'It's to do with my mentor teacher,' says Allan. The words have come out more forcefully than he expected. He wonders if he's being rude.

'Go on.'

It's not really the prac itself,' says Allan, wanting to sound more in control but not sure he's managing it. 'There are challenges, and I stuff up sometimes, and some of the students take advantage of my lack of confidence, or the fact that I don't have an iron will like Susan seems to have ...

'Susan is your mentor?'

'Yes.'

They sit in silence for a moment. Alan looks lost in thought.

‘You were saying,' says the counsellor when she feels Allan drifting away. Allan frowns. He's struggling to remember the thread.

'It's not the prac, it's Susan. I knew from the first day or so on this prac that I wasn't going to get on with my mentor Susan. She was so ... I don't know... so arrogant ... distant ... so cold. Never being outright critical, but just undermining me all the time, or trying to. Saying little things that conveyed her disapproval, or her sense that I was young and idealistic and didn't know how the real world worked.'

'She made you feel naive, inexperienced.'

'She made me feel like I was a child with a disapproving parent. I wanted to tell her to stick it, but I couldn't. She decides whether I pass or fail, she writes the report.'

"You felt powerless.'

I felt furious. All pent up inside. It's still there, that's why I'm here. I can't concentrate. It's how unfair it is, how unsupportive she's been. I know I've made mistakes, I know there's stuff I need to learn …’

Allan stops mid-sentence. This isn't helping. He's feeling defensive again, as if he's exposing his weakness to this stranger, just as he had done with Susan.

'You stopped mid-sentence.'

I don't want to talk about it.' ‘It's painful to talk about.'

'It's a waste of time. Talking.'

'It brings up unpleasant feelings.'

Again there's silence. Allan looks out the window, wanting to be somewhere else. For some reason, he remembers how he used to stare out the window at home, wanting to be somewhere else. Or how, when he's writing, really deeply writing, or when he's reading a really good book, it feels like he actually is somewhere else. Maybe it's just a big mistake, this teaching thing. Maybe he should chuck it all, and try his hand at doing what he's always secretly wanted to do, try to make do as a writer. Well, not always secretly! It was one of the sources of conflict with his mother, that ambition to be a writer. Join the real world, she seemed to imply, though she never said it outright. He found it so undermining.

5.

Perhaps, as this scene with the counsellor seems to suggest, the conflict with Susan is not unconnected to Allan's family history. Perhaps, when we are thinking about pre-service teachers and their mentors, there are subtle unconscious factors at play, to do with the participants' family backgrounds.

But Deleuze and Guattari (1977, p. 49) warned against boxing a life within an indefinite parental regression. James Hillman 1983), the maverick of the psychoanalytic tradition, put it this way:

Physicists, theologians, Zen teachers - all said the map is not the territory. Psychologists seem not to have learned that. All these explanations of human life are for me fictions, fantasies. I like to engage them on that level, but only as fictions, as archetypal fantasies. They may have therapeutic value, like any story can have. They may help the therapist get a second-level structure, an ordering grid, while he is in the middle of the confusion. But psychodynamics - and I don't care whether role-playing theories, infantile development theories, or the Gods themselves - keeps us in explanations. We cannot explain the psyche. We are the psyche. The soul wants imaginative responses that move it, delight it, deepen it ... explanatory responses just put us back into positivism and science - or worse, into delusion, a kind of maya or avidya, an ignorance that makes us believe we know. (p. 38)

And so we turn to a second tradition that contributes to our ability to delve into what lies beyond our rational gaze.

Creative artists, and particularly (in this case) writers of fiction, are less interested in explaining and more concerned to agitate, provoke, move, seduce, disturb, and animate, often by paying attention to what is below the surface, hidden, disguised, repressed, or invisible. Writers attempt to alert us to what Rilke called "the rustling resonances" (Dowrick, 2009, p. 220) and what Maxine Greene says is "the ordinarily unseen, unheard and unexpected" (Greene, 1995, p. 28). They ask us to pay more attention to the complicated and nuanced landscapes characterised by ambiguity, conflict, and surprise (Frankham & Smears, 2012). They help us to see life "from the point of view of the participants in the midst of what is happening, to be privy to the plans people make, the initiatives they take, the uncertainties they face" (Greene, 1995, p. 10). They map "the ordinary affects," those "varied, surging capacities to affect and be affected that give everyday life the quality of a continual motion of relations, scenes, contingencies and emergences" (Stewart, 2007, pp. 1-2).

There are now a number of ethnographic sociologists and educationists who include the approach of the creative artist in their scholarship. Their work goes by many different names - arts-based research (Barone & Eisner, 2012), auto-ethnography (Bochner, 2012), fictional ethnography (Reed, 2011), postmodern emergence (Somerville) - and sometimes under no particular label (Clough, 2002). There are differences and debates among them, about the extent to which their work exists to reveal hidden complexity (Barone, 2000; Britzman, 2003; Clough, 2002; Greene, 1995; Somerville, 2007) or create particular affects (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987; Hickey-Moody, 2013; Reed, 2011; Richardson, 1997). Most of these ethnographers would claim that this methodology does a bit of both. It is, says Art Bochner, "a means of knowing and a way of telling. (It) not only represents but also creates experience, putting meanings in motion" (Bochner, 2012, p. 157).

Peter Clough (2002, p. 8) describes this work as follows:

As a means of educational report, stories can provide a means by which those truths, which cannot be otherwise told, are uncovered. The fictionalization of educational experiences offers rescarchers the opportunities to import fragments of data from various real events in order to speak to the heart of social consciousness - thus providing the protection of anonymity to the research participants without stripping away the rawness of real happenings ... (These) are stories which could be true, they derive from real events and feelings and conversations, but they are ultimately fictions: versions of the truth which are woven from an amalgam of raw data, real details and (where necessary) symbolic equivalents.

6.

Susan stands at the window, car keys in hand, and watches her mother in the vegetable garden. Her mother is still in her dressing gown, which is on inside out and bunched around one shoulder, and she is staring at something that Susan cannot see. Perhaps she's just lost in thought. She is holding a hose, but the hose is pointed aimlessly into the air and there's a fine spray making short-lived rainbows in the early morning light. Susan notices that a mist is settling on the back of her mother's neck and beginning to wet the dressing gown, but her mother is not bothered, maybe not even aware. She'll soon be soaked, but Rosie will be here in a minute, should in fact have already arrived, and Rosie, wonder woman that she is, will patiently fetch Susan's not-so-elderly mother from the garden, towel her down and, while talking to her about what a lovely morning it is and aren't the veges doing well, will soothe away the distraction and bring her back to the now. In fact there's Rosie's car pulling up outside, and Susan turns from the window, picks up her bag with her school materials, then knocks on the window to get her mother's attention, wanting to wave goodbye. But her mother just frowns, as if resenting the disturbance, and continues her search for what isn't there.

‘She's outside', says Susan as she opens the door for Rosie. 'She's out there getting soaked. I have to go, sorry. Thanks Rosie, again. Really, I don't know what I'd do ...’

Rosie pats her on the arm, puts down her things, and opens the back door.

Once in the car, Susan is again visited by that sense of relief she often feels as she backs down the drive; work has always been a welcome world away from the worry. There are challenges there, of course, running an English Department in a time of constant and often pointless change, but she protects her staff from the worst of it and has set up routines and procedures that actually work. The previous Head of Department, Winnie with the orange hair and the loud smoke-affected voice, was an inspiring teacher but a chaotic administrator, and Susan knows that the staff appreciate the order and predictability that she's managed to bring to their work.

She has a pre-service teacher in her classes at the moment. Allan. Other Heads of Department farm out the pre-service teachers, but Susan likes to take them herself, partly out of a sense of duty, partly because she doesn't like cleaning up the mess when it's not done well.

She wonders about Allan. He is difficult to pigeon- hole. Keen. Obviously intelligent. But a bit arrogant too, as if he knows best, as if he knows the young in a way that an older teacher can't. A bit groundlessly optimistic, thinking that his youth, his wide reading, his enthusiasm and empathy are enough to transform her class from its usual well-behaved but limited collection of strugglers into some dynamic community of thinkers and readers and writers. She smiles, remembering the interaction yesterday with Mel. You calling me stupid, sir?' Poor Allan. He looked so lost.

She shouldn't smile. She's been teaching for the best part of thirty years now, and she still remembers vividly her own first years as a teacher and that feeling of helplessness in an out-of-control classroom. She still has nightmares, actually, and last night there was a particularly unsettling one.

In her nightmare Susan was standing in front of a class of secondary students, sensing their mounting restlessness and desperately trying to hold their attention. But none of them were paying the slightest notice, none of them seemed even aware of her presence. Desperately she tried every trick she knew: cajoling one sub-group, trying to beguile a second with a story or an interesting fact, threatening a third. But increasingly she felt weak and underprepared. She sensed that the students were about to riot, or walk out. There was one particular boy, the only one in the class who seemed aware of her presence, who started to taunt her, suggesting Susan was a fraud, that she read rubbish and couldn't write. He was looking up at her, a supercilious knowing grin on his face, taunting Susan, making her feel inadequate and ignorant. There was a stick in Susan's hand. A cane. In her dream Susan lunged at the boy, trying to get at him, bringing the cane down first on his neck, then on his arm, but he hardly flinched, just continued looking up at her and smiling. The cane then turned to cloth. Susan kept trying to hit him, but he just laughed. Susan was suddenly aware, as she lashed out with her pathetic piece of cloth, that she was now naked and that all the class was watching and laughing.

It is strange that, after all these years, versions of this nightmare recur. Susan takes a deep breath as she drives, trying to calm the disquiet left over from the dream and from the morning at home.

7.

Post-structuralism adds other scholarly lenses through which we might peer at the world and be reminded of, and affected by, its un-pin-down-able complexity.

The structuralist imaginary sees a world characterised by a single narrative with atomistic individuals (Allan, Susan), groups (teachers, students), or societies positioned at different points, some at an early stage (like Allan) needing to be inducted by others (like Susan) into the dominant narrative. It imagines space (the classroom, the staffroom) as a collection of closed and contained systems, susceptible to structural analysis. It assumes the existence of established hierarchies and relationships.

The post-structuralist imagination sees a quite different picture. It imagines space (a classroom, a staffroom) as an open, contingent, fluid, and chaotic site containing not a single narrative but many (Allan's, Susan's, their partners' and family's, the school's, the various students,' the parents', the community's, together with various aspects of the nonhuman world). Instead of given identities (Allan the creative but inexperienced pre-service teacher, Susan the unsympathetic realist), it imagines identities shifting and being shaped by context, discourse, and circumstance. It imagines multiple intersecting life-trajectories coming in and out of connection, affecting and being affected by common worlds with complex and fluid interactions and relationships.

We come in and out of awareness of the myriad flows and shifting rearrangements, and we never know them all completely. Life is, to a large extent, shaped by the invisible.

Fiction has a particular capacity to gesture towards this complex world by "seeing people big" (Greene, 1995, p. 10), through its ability to magnify the little moments, hint at the unseen and inexplicable, create a sense of ambiguous complexity. Here there is room for the irrational, the messy, the chaotic; we are encouraged to see beyond rational intentions and emancipatory urges (Allan's, Susan's). It is the space described by Doreen Massey (2005, pp. 11-12) as follows:

In this open interactional space there are always connections yet to be made, juxtapositions yet to flower into interaction (or not, for not all potential connections have to be established), relations which may or may not be accomplished. Here, then, space is indeed a product of relations (first proposition) and for that to be so there must be multiplicity (second proposi-tion). However, these are not the relations of a coherent, closed system within which, as they say, everything is (already) related to everything else. Space can never be that completed simultaneity in which all interconnections have been established, and in which everywhere is already linked with everywhere else. A space, then, which is neither a container for always-already constituted identities nor a completed closure of holism. This is a space of loose ends and missing links.

8.

Allan looks over towards Susan after the students leave. She is still sitting in the back row. There is something about her tight smile that is unsettling. Allan isn't sure whether to stay standing at the door or walk over and sit down next to her.

'The students certainly seemed to be having fun, ' Susan says. Allan's not sure he likes the way she says the word ‘fun'.

He stays standing, frowns, searching for clues as to what Susan is implying.

"Yes,' he says, 'they seemed to. Do you think it went alright?' He is struggling to keep his tone appropriately open, as if her opinion matters to him. Which, in a way, it does.

'That was OK for a first lesson on a topic,' Susan says in the same careful way. 'But I wouldn't get carried away. It will get harder when they're not just having fun.'

OK? It was just OK?? Allan feels something between panic and anger. He tries desperately to think of the right question to ask her, but he is tangled up in thoughts he can't say out loud. Does she think it was bad? Is she stupid? Couldn't she see how good it was, how engaged they were? He resists the impulse to justify himself, to show her the comment he's just read. She'd just criticise the spelling.

‘There were some fun activities in there,’ Susan continues. 'I was wondering, though, in your normal lessons, is that how you would conduct them? That many activities?'

Allan had divided the lesson into more than half a dozen segments, the longest fifteen minutes and the shortest two. He'd wanted the students to be on the move, to be alert, to feel physically involved. Shakespeare, he was convinced, needed to be experienced with the whole body, not just from the neck up. There was the brief introduction where he'd played them a short extract from Shakespeare in Love which showed what an Elizabethan theatre and crowd looked like. There was a writing activity getting the students to freely-associate with the names 'Romeo’ and ‘Juliet’. There was some sharing in pairs of a first experience of being attracted to someone, appropriate or otherwise (there was laughter during this, and also intense listening to the stories being told). Then, together as a whole class, they'd talked about what the opening sonnet in the play might be trying to achieve. Allan had then used the lines he'd learnt by heart the night before to get the students representing, in a light-hearted but active way, twelve key moments from the play, and he could sense them now coming to grips with the plot. Next, he'd got pairs to stage an argument of their own choosing, the more violent and loud the better, as a prelude to looking at the first scene when the Capulets and Montagues confront each other. The lesson had concluded with the written reflections he was holding now in his hand.

That many activities? Wasn't that what made it work so well?

‘I'm... I guess not,’ Allan stutters. 'It would depend on the lesson topic.’ He is just mouthing words now; he has no idea what he is meaning. "I plan to use those activities quite often,' he hears himself saying, though he's thought no such thing.

‘I wouldn't use them too often. And not so many. It sets up expectations that will be difficult to fulfil. Makes them unsettled.' Susan pauses, then comes in at another angle. 'How were you planning on introducing content?'

Again Allan feels stumped. Hadn't there been content in today's lesson?

'Uh ... well, I guess I would explain a scene or a theme and then use those sorts of activities to explore them.’ Again this is so unlike him. He's talking drivel.

Susan frowns. ‘I'm not sure if I see how that would work. You need to give explicit instructions, you need to continually explain to the students why they're doing what you're asking them to do. They need to know the learning outcomes and where the lesson fits in. That's why we do lesson plans.' Allan had given her a lesson plan before the students arrived, but he can't now remember anything about it. It had seemed like a dead official document. His lesson, he felt sure, was alive and engaging. It was unpredictable, but wasn't that a good thing? Wasn't it full of animating surprises?

"And Allan, she adds, "don't be afraid of using the whiteboard and having students take notes. They need to have some concrete notes taken down to help them revise.'

Allan mentally flails through his memories from uni, trying to find some irrefutable reason why her advice is bullshit. Surely, surely it was more than a highly enjoyable waste of everybody's time? Surely there's a bucket load of theory to say that the lesson he has just given was spot on? But his mind is muddled. He can't think straight.

‘Well, today I just chose mostly introductory topics, but you can use those activities to look at some complicated stuff … actually at uni we often use those sorts of activities and I find they really help me learn.' Again this is feeling so weak, so insubstantial!

Susan smiles. To Allan, it seems an infuriatingly condescending smile.

‘You'll find there are some things you learn at university,' she says slowly, ‘that just don't translate very well into a real classroom. I can see you might find it quite frustrating. Don't worry, it might take a while but gradually you'll work out what is helpful and what just doesn't work. Most new teachers feel that way, It's a bit of a roller coaster. Look, let's talk some more later. You tidy up here a bit, ' Susan seems to make a point of looking around at the desks pushed out of their usual order, at the bits of paper on the floor, 'and we'll talk some more later.'

9.

The curriculum theorist James Macdonald (1995) suggested that there are three main scholarly epistemologies or methodologies: science, critical theory, and mythopoetics. The scientific is aimed at explaining for control purposes. The critical is aimed at reducing illusion in order to emancipate. The mythopoetic is wanting to draw on "the use of insight, visualisation and imagination in a search for meaning and a sense of unity and well being" (Macdonald 1995, p. 179).

The three methodologies (science, critical theory and poetics) are contributory methodologies to a larger hermeneutic circle of continual search for greater understanding, and for a more satisfying interpretation of what is. (p. 180)

These three methodologies, he suggested, are collectively aimed at "providing greater grounding for understanding" (p. 176) of a world which we know is far more complex than our minds can possibly comprehend.

Macdonald can be seen as standing at that point in our scholarly history when there is a shift from a modernist to a post-structural consciousness. At one level (and in certain academic communities), the shift has evolved and become something quite excitingly revealing of a different way of conceiving the world (in the kinds of ways described earlier in this paper). But at another level we are still stuck in structuralist ideas about fixed truths and stable identities.

Macdonald's first two categories (the scientific and the critical-emancipatory) have such an exclusive hold on our more public and institutional thinking (in universities, in schools, in the press, in our public debates) that the mythopoetic tends to be marginalised, excluded, under-valued, despite its demonstrated capacity to include in its purview aspects of what is that the other methodologies are not able to see. Macdonald, at least, thought so.

…non-scientific curriculum theory is a mystery to most educators... It is a mystery because it deals with the mystery. (p. 182)

There is, perhaps, a tendency in teacher education to bunker down into familiar methodological silos and dismiss the mythopoetic as a subjective diversion.

10.

SCENE: EDITORIAL MEETING OF 'EDUCATIONAL MATTERS' JOURNAL

Three reviewers of the journal Educational Matters have joined up via Skype. Each has been reading a copy of 'Both alike in dignity', and their initial responses to the article are so divergent that the editor has asked them to see if they can find some common ground before a decision is made about the manuscript.

Christine Evans is a university academic with a background in linguistics and a strong commitment to social justice issues. For some time now she has been urging the journal to take a more political stance in its editorials and in its decisions about manu-scripts. She wants to see the journal exposing the impact of current policies and practices on the disadvantaged and marginalised. She looks forward to the day when the journal is known for its clear clarion call.

Tony Roberts is a founding member of the journal. He thinks the quality of too much current educational research is lightweight and he finds its reputation amongst policymakers depressing. He consistently urges the editorial committee to publish more articles that have scientific validity, articles that are evidence-based, with a strong quantitative component, likely to be used to shape policy by politicians, bureaucrats or school leaders.

Melanie Price is a secondary English teacher doing a six-month internship with the joumal. She has been brought onto the editorial committee because she is also a writer, and there's been a concern in the past that too many of the journal's articles have been unreadable.

TONY: Do they actually pay him to write this stuff?

MELANIE: Huh?

TONY: Does his Educational Faculty actually pay him a salary to write like this? This isn't research. He's made it up! It's got no empirical grounding, no validity. It's just fiction.

MELANIE: Hang on a bit. He hasn't just made it up. He worked with three beginning teachers, and surely you're not saying their experience isn't valid?

TONY: I stand corrected. He didn't make it up. They did. It's a fabrication, no matter how you look at it. And even if it's a roughly faithful representation of some bit of their experience (and we've no way of knowing if it is), it's still just four people's experience. And three of them have just begun their teaching careers! I'm sorry, but I can't see the value in it. It will have no impact; it is proving nothing.

CHRISTINE: Melanie, I enjoyed the piece, but I have to agree with Tony here. You know; if it had been accompanied by some clear analysis of the unequal power relations between the two characters, Allan and Susan, or of the way a particular set of assumptions about the nature of teaching and learning was embedded in the language of the Professional Experience Report... If this story had been accompanied by an analysis like that..

MELANIE: But those analyses are everywhere in the journals! This is giving us something different.

CHRISTINE: They're everywhere because they are what matters. That's what journals are for. To provide us with intelligent probings into the hidden power structures which bolster educational inequalities and inefficiencies. To show us why some kids are failing, or why some teaching programs work. This story says nothing about these things.

MELANIE: It says something about why some good young teachers are leaving the profession. It says something about how tangled and complex it is to be a member of a school faculty.

TONY: It says more about Steve's fertile imagination than about anything real. If we want to know why young teachers are leaving, we need to study patterns over a period of time. We need to see the correlations once we've assembled the evidence. That's what's going to make an impact.

CHRISTINE: Melanie, you said that this was different, and you're right, it is different. But that's no reason for us to publish it. What is it contributing to knowledge in the field? Where is the evidence that it's theoretically informed? What's it telling us that we didn't know before?

MELANIE: (pauses, then slowly, as if trying to find the words for something elusive): 1 liked it I wanted to read more.. I get a sense of the lived life of a teacher, with all its hilarious and tragic moments…. I felt engaged, first siding with Allan as he put his heart and soul into his English lesson, and then with Susan as she balanced the various personal and professional pressures she was under... The ending seemed so real, too, frightening because I could imagine something like that really happening.

TONY: But what does it prove?

MELANIE: Maybe the purpose of an article like that isn't to prove anything.

CHRISTINE: So what's its point? What's its purpose?

MELANIE: I don't know. It's like all good fiction, I guess. Or a good film. It draws you in. It unsettles you. It makes you realise that things aren't always quite what they seem on the surface. Reading the story made me think about my teaching, and whether I was more like Alan or more like Susan. About conflicts I've had with other teachers. About what I might do differently.

TONY: That might be what literature and films are for, but it has no place in Educational Matters. If this group want it published, they should send it to a literary journal.

CHRISTINE: I agree. It doesn't belong.

11.

The lecture hall is almost full, with over 200 students, most of them wondering how they will manage on that nerve-wracking day when they stand, for the first time, in front of a secondary class. For some, learning the theory at university has seemed only marginally relevant; for others, it's been both stimulating and just the preparation they craved. But all are nervous. Prac starts in less than a fortnight.

The lecture, it turns out, is not about practicalities at all. Instead, the lecturer tells the story of 'Both alike in dignity'.

The telling of the story takes the full hour:

As the students file out, many are thinking about the final scene, wondering if Allans fate - his prac terminated because of one dreadful misjudgement - could possibly be their own.

... Allan sits at the bus stop, his books and papers in his backpack. None of the other staff" would look him in the eye as he packed up to 80, and Susan was elsewhere. It's been a long and lonely hour. He's sent a text to Paul, who says he'll come and pick him up asap, but still there is no sign. Allan has decided to get the bus; waiting outside the school is just too painful.

Someone touches his shoulder lightly. 'Hello sir, ' says a bright voice behind him. Allan turns. It is Rebecca, the girl from the front of his class. What are you doing out here sir?

Aren't you coming to class?'

I've been transferred,' he lies. 'I have to go and teach somewhere else.'

Rebecca looks shocked.

'Oh no, that's awful,' she says. Allan realises it is the first time he's heard her say anything except answer the roll. 'I liked you. You were a good teacher. You were cool. That sucks.'

At a later tutorial, the pre-service teachers talk about the impact the story has made.

This week's lecture made me feel quite sad, and potentially anxious about how I might respond to a situation like that.

While I listened to the story, I was both amused and completely baffled at the conflict between Allan and Susan.

The idea of standing in front of a class knowing that I am being watched and judged, it's terrifying, worrying and intimidating.

It was quite a revelation (and a shock!) to consider the fact that I might have a mentor who reacts negatively to my style.

These responses point to the affordances of the mythopoetic, to its alchemic possibilities.

The mythopoetic agitates. Listeners are opened up. Something unknown has been introduced, or something felt but not yet named is articulated. A gap appears, something very like a vacuum. It is uncomfortable. There is an impulse for closure, for some kind of resolution. Stories enter bodies, and molecules are agitated.

The mythopoetic complicates. Subtlety is added to an understanding of a phenomenon. A hidden factor is revealed. A cause vaguely visible in the shadows is illumined. The existence of a complex web is articulated. Simplistic solutions are shown to be inadequate.

The mythopoetic inducts. Stories create community. Initiates tell stories in order to press their claims for membership, to attempt to mate with a desired world; those standing at the gates, the leaders and elders, tell stories to initiate novices into the ways of the group. Stories create connections, they foster relationship, they induct. Stories have always had that function.

The mythopoetic animates. Energies are released when a good story is told and heard. The early agitations lead to energetic attempts to restore equilibrium, to imagine or find a way through complexities, or a way to eliminate conceptual gaps and vacuums. The affect functions as an impulse to act.

It seems we live in increasingly rational, practical, and utilitarian times. The mythopoetic, as a consequence, gets squeezed to the margins, seen as an escape or respite from the serious business of schools and universities.

Instead, it performs a vital function.

Perhaps, if there were more of it, teacher education might be a more balanced and enlivened site.

__________________________________

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the contributions of CoCe Edwards, Libby Pittard, and Hannah Germantse as co-authors of the story discussed in the article. He also wants to acknowledge the valuable feedback he reccived from his colleagues at the University of Canberra and also from Saskia van Goelst Meijer, Jen Webb, and Anna Hutchens.

The story "Both alike in dignity" was first published in English in Australia (2013, 48:2) and permission was received to use extracts from the story in this article.

Note

1. All sections in italics are fictions, following Peter Clough's description of this kind of writing: "(These) are stories which could be true, they derive from real events and feelings and conversations, but they are ultimately fictions: versions of the truth which are woven from an amalgam of raw data, real details and (where necessary) symbolic equivalents" (Clough, 2002, p. 8). Some are extracts from our story "Both alike in dignity," others were written for this present article.

References

Barone, T. (2000). Aesthetics, politics, and educational inquiry (Vol. 117). New York, NY: Peter Lang

Barone, T., & Eisner, E. (2012). Arts based research. London: Sage.

Bochner, A. P. (2012). On first-person narrative scholarship: Autoethnography as acts of meaning. Narrative Inquiry, 22(1), 155-164. doi:10.1075/ni.22.1.10boc

Britzman, D. (2003). Practice makes practice: A critical study of learning to teach (Rev. ed.). Albany: State University of New York Press.

Campbell, J. (1949). The hero with a thousand faces (2nd ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Clough, P. (2002). Narratives and fictions in educational research. Buckingham, PI: Open University Press.

Davies, B., & Gannon, S. (2006), Doing collective biography. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1977). Anti-oedipus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. Middlesex: Penguin Books.

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus. Capitalism and schizophrenia. London: The Athlone Press.

Dowrick, S. (2009). In the company of Rilke. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Ellenberger, H. F. (1970). The discovery of the unconscious: The history and evolution of dynamic psychiatry. London: Fontana Press.

Frankham, J., & Smears, E. (2012). Choosing not choosing: The indirections of ethnography and educational research. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 33(3), 361-375.

Greene, M. (1995). Releasing the imagination: Essays on education, the arts, and social change. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Hickey-Moody, A. (2013). Deleuze's children. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 45(3), 272-286. doi: 10.1080/00131857.2012.741523

Hillman, J. (1983). Interviews. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

Macdonald, J. B. (1995). Theory as a prayerful act: The collected essays of James Macdonald (B. J. Macdonald, Ed.). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Massey, D. (2005). For space. London: Sage.

Reed, M. (2011). Somewhere between what is and what if: Fictionalisation and ethnographic inquiry. Changing English: Studies in Culture and Education, 18(1), 31-43. doi: 10.1080/ 358684X.2011.543508

Richardson, L. (1997). Fields of play: Constructing an academic life. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Shann, S., Edwards, C., Pittard, L., & Germantse, H. (2013). Both alike in dignity. English in Australia, 48(2), 23-32.

Somerville, M. (2007). Postmodern emergence. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 20(2), 225-243. doi: 10.1080/09518390601159750

Stewart, K. (2007). Ordinary affects. Durham: Duke University Press